WASHINGTON — The number of licensed foster homes in Washington dropped nearly 50% in the past year, a larger drop than in any state, according to a report released Thursday by the Chronicle of Social Change.

The annual report, which aggregates state-reported data with federal data from the Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System to project national foster care numbers, found the number of foster homes nationally rose to between 220,000 and 225,000.

In D.C. researchers counted 218 licensed homes this year in the city, a 49.2% decrease from 2018.

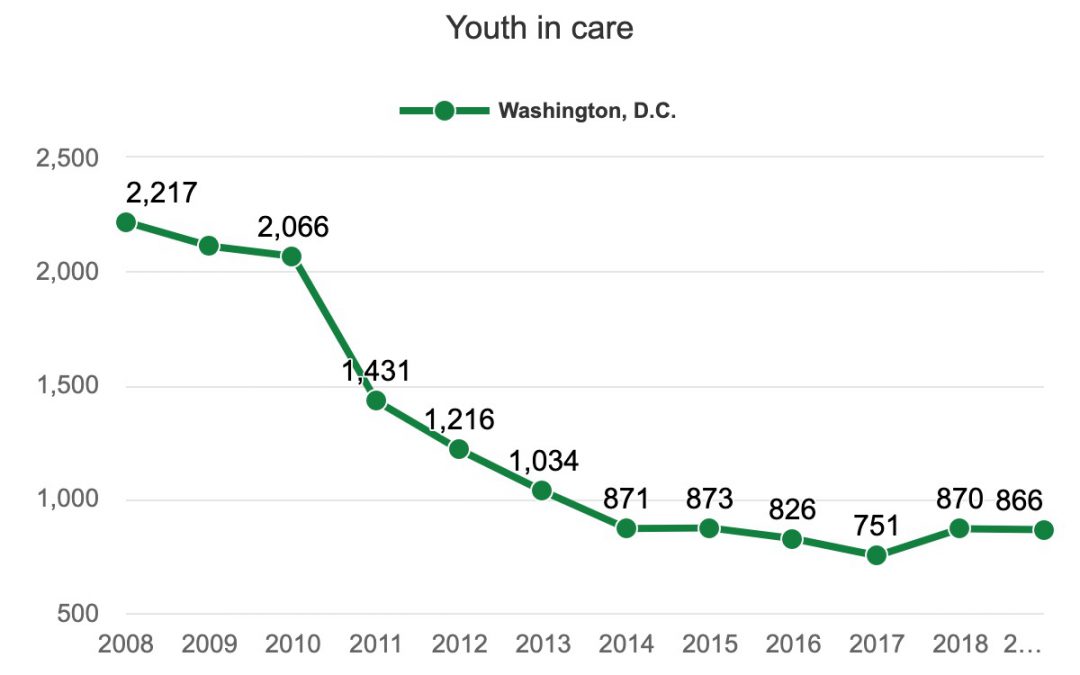

Washington Child and Family Services Program Manager Mary Chell said the decline is not a problem because the city has enough beds for its 866 youth in care. Chell, who is an adoptive parent herself, hosts monthly recruitment events in various wards, including one on Oct. 8 that has yielded three foster parent applications.

“There is an incredible motivation in the human existence to help, and we tap into that,” she said.

courtesy of the Chronicle of Social Change

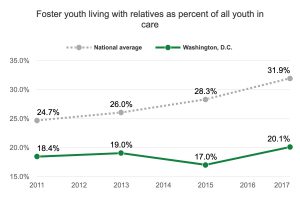

Chronicle of Social Change Editor-in-Chief John Kelly said the decline in licensed homes in D.C. may be the result of a bigger push to place children with family members, which falls outside the licensed home category. Chell emphasized the city’s desire to place children with relatives to avoid the need for foster care, in conjunction with strategies such as therapeutic care and comprehensive in-home social work services.

“We have an increasing amount of kinship foster parents coming on board,” she said. “It’s a big mission. It always has been.”

The number of foster children nationally steadily increased since 2010, according to data from the Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System, peaking in 2017 with 443,000 children. The Chronicle projected 428,006 foster children this year.

courtesy of the Chronicle of Social Change

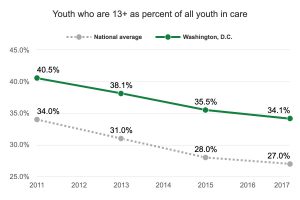

The new Family First Prevention Services Act limits federal spending on group homes and institutions to two weeks per child. It’s a move to limit congregate care and encourage placement with relatives, though it may harm youth in care who rely on group homes, Kelly said.

“The long-term goal of the two provisions of the Family First Act are to lower the number of kids in foster care,” he said. “But in the short term, the ambition of limiting congregate care—we feel that could lead more states to need more foster homes, especially ones that serve older youth, who are disproportionately the kids that end up in group homes and institutions.” About one-third of foster children in Washington D.C. were older than 13 years old in 2017, according to the federal data.

Read the report at fostercarecapacity.com.