Carolyn Bourdeaux lost the 2018 House race in Georgia’s 7th Congressional District by 433 votes. Despite the fact that the district hasn’t had a Democrat representative since the 1990s, it was the closest race in the country, with five-term Republican incumbent Rob Woodall barely holding on to his seat in a quickly diversifying region outside of Atlanta.

It didn’t even take until the end of the year for Bourdeaux to decide she would put her hat in the ring once again. In fact, she said the loss had even felt “more like a victory” because of the razor thin margin.

“I had a big thank you party in December, and basically everybody there was going ‘Ok, we’re ready to go. Let’s relaunch,’” she said. “So that was it.”

Bourdeaux, a public policy professor and former state budget official, is part of a cohort of 2020 “rebound” women candidates—women who ran and lost during 2018’s “Year of the Woman” but who are running again this year. The Center for American Women and Politics at Rutgers University has identified over 80 rebound candidates, and estimate that 14% of women who lost congressional or statewide races in 2018 are likely to run again.

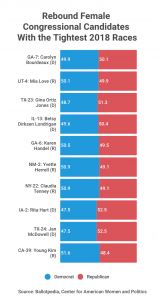

The majority of women on CAWP’s list are Democrats, which reflects the breakdown of federally elected women: of the 101 women currently in Congress, 88 are Democrat and 13 are Republican. Key Republican rebound candidates are Karen Handel, who lost Georgia’s 6th Congressional District to Democrat Rep. Lucy McBath by a single percentage point, and Young Kim, who lost California’s 39th Congressional District to Democrat Rep. Gil Cisneros by 3 percentage points.

Lisa Ring, another Georgia Democrat, said her motivation to run again stemmed from creating a strong foundation in 2018. Ring lost Georgia’s 1st Congressional District in 2018 to Rep. Earl Carter by about 15 percentage points.

“After the election, we had put in two years of work and it just seemed like we weren’t done yet,” she said. “We had gained so much. We did better than any other Democrat in our district for close to 30 years. We raised more money. We upped voter turnout for Democrats by 11%. So we really made a difference in the district, and I just felt a responsibility to keep going with that.”

Ring retained her same Savannah campaign office and volunteer team after taking a week to decide to run again.

“I just filled out the paperwork and we were on our way,” she said.

Bourdeaux is also relying on her 2018 framework this time around, though on a much larger scale. She raised $310,000 between October and December 2019, compared to “$125,000 or so” per quarter last election.

“That is a result of building that community of people who know me, who know the district, who are engaged and excited about this race,” she said. “That was what was built in 2018. We’re able to continue to build, but we start at a much, much higher level this time.”

Amanda Hunter, communications and research director at the non-partisan Barbara Lee Foundation, said a candidate’s quick turnaround can help them in the subsequent election.

“It’s helpful for women candidates to keep in mind that if they want to keep the door open, their concession speech is a great point to start reframing the issues and set themselves up for success in the future,” she said.

Hunter said that historically, an electoral loss is a “prerequisite” in a male politician’s career, but can often lead to blame and shame for a woman. The foundation wanted to study this phenomenon after the record number of women candidates in 2018 in order to guide the women who would inevitably lose those elections.

That post-2018 election survey found that voters do not punish women who lose their races and are, in fact, open to a candidate who relaunches themselves during the next cycle. Even after hearing a negative news story about women who lost congressional races, 76 percent of respondents said they didn’t have any doubts about voting for a woman candidate in the future.

“The good news is that this research found that women can pick themselves up after a loss and be successful,” Hunter said. “Voters say they will not hold it against a woman if she’s lost in the election.”

Many rebound candidates are taking the steps experts at the foundation say can be critical to a second election cycle: quickly restarting their campaign, staying involved in public life, and focusing their messaging on issues most important to voters.

Joan Greene said she is running again because the issues she ran on in 2018 still persist in Arizona’s 5th Congressional District. The Democrat lost to Rep. Andy Biggs by 19 percentage points in 2018. She said she frames the run not as a rebound, but as a “continuation.”

“The message hasn’t changed because the need hasn’t changed, except now three years later it’s even more dire,” she said. “We have people in [Congress] who are no longer whispering that they want to take away vital, essential needs for communities all over the country.” Greene said that a key part of her strategy is appealing to every voter, not just registered Democrats.

Though the messaging and strategies are often just slight revisions from their 2018 experience, rebound candidates, especially in districts skewing purple, are facing the added challenge of increased visibility. For Bourdeaux, that means both more institutional support from the Democratic Party, but also more scrutiny. She said that at least one Republican opposition researcher regularly shows up to her campaign events now.

“I’m actually excited, because it means they know I’m in a good position to win,” she said.

Rebound candidate or not, the culture of women in politics has continued to shift beyond just the “Year of the Woman.”

“We’ve seen women in the past few years running more as their authentic selves,” Hunter said. “Instead of trying to fit into a boxy suit and stand behind a podium, women are what we call 360-degree candidates. They’re showing the whole of their experience and how they bring that to the campaign trail and to the job.”