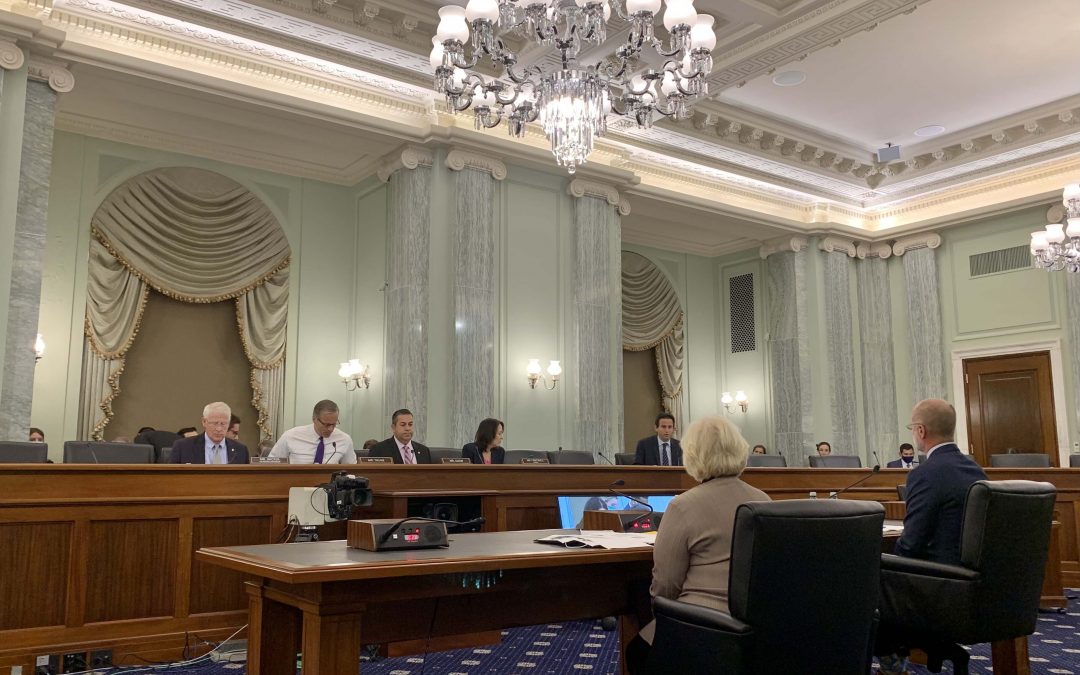

WASHINGTON — As the use of telehealth expands and becomes a more integral part of Americans’ lives, financial investment is needed to mitigate barriers to broadband access and workforce shortages, health care professionals warned senators on the Commerce, Science, and Transportation Committee on Thursday.

For many Americans, telehealth has become indispensable, helping many overcome geographic restrictions and promoting equitable and timely health care access. Since the start of the pandemic, the number of health care providers equipped to provide telehealth services rose from 43% to 95%, according to the Department of Health and Human Services.

Even so, 19 million Americans — 14.5 million of whom live in rural areas — are barred from accessing it due to low-speed broadband service, according to the Federal Communications Commission.

The hearing comes at a critical time for Congress. For weeks, Democrats and Republicans have been debating a sweeping infrastructure bill that would allocate $65 billion for broadband infrastructure and connectivity.

“Families must be able to talk to their doctor without worrying about hitting a data cap,” said Communications, Media, and Broadband Subcommittee Chairman Ben Ray Luján, D-N.M., during Thursday’s hearing. “We must focus on solutions that work for underserved and unserved communities.”

The president of the American Academy of Family Physicians told lawmakers the full benefits of telehealth cannot be accessed without expanding broadband services.

“More needs to be done to ensure that everyone has access to telehealth,” said Dr. Sterling N. Ransone. “When we can monitor our patients closely we can keep them out of our hospitals, help the patient-doctor relationship, decrease costs and promote competition.”

Ransone recognized that barriers to telehealth go beyond broadband access.

“It’s not enough to expand access to broadband,” Ransone said. Congress must invest in infrastructure so that every American has the tools and knowledge to leverage it.”

Telemedicine allows patients to connect with professionals who may not live in their area, but, according to Ransone, licensing requirements for medical professionals between states pose barriers to out-of-state care, even to those who travel or go to college.

“I think I can give [my out-of-state patients] the best care, because I’ve known the patient since they were an infant,” Ransone said. “We think that it’s incredibly important that there is still some state control for safety reasons over the physicians, although we think it needs to be less burdensome to apply in other states and less costly to apply in other states.”

The head of the world’s largest telemedicine provider also saw the need for state reciprocity in telehealth care, but for a different reason.

“Telehealth is part of the solution to geographic shortages in expertise,” said Avel eCARE President Deanna Larson. “We don’t have a lot of specialists in so many places. We need to think about a wider cast that can cross state lines.”

University of New Mexico Professor of Medicine Dr. Sanjeev Arora, said the biggest problem he sees in U.S. health care today is shortages of labor.

“There are simply not enough experts anywhere to serve everyone that needs help,” Arora said. “Patients not just in rural areas but in urban areas have to wait weeks or months to get the care they need. Telehealth does not overcome the overarching problem: we need task shifting.”

Beyond labor shortages, Arora also cited knowledge shortages — particularly in rural areas.

“We need to fundamentally reorient our health care system,” Arora says. “We need policy incentives to democratize medical knowledge, because there is an enormous shortage of knowledge in rural areas.”