W

ASHINGTON – A Coast Guard patrol boat that collided with a passenger vessel in San Diego Harbor in 2002, killing an 8-year-old boy, was going dangerously fast and the oversight that could have prevented the accident was inadequate, the National Transportation Safety Board said Tuesday.

The board issued its final report and safety recommendations following an 18-month investigation of the Dec. 20 accident during the city’s Parade of Lights. Although no crew members interviewed by investigators identified excessive speed as a factor and the patrol boat’s systems failed to record speed data on the evening of the accident, a witness’s 12-second video clip, taken just 100 yards from the crash spot, showed the boat had been speeding.

San Diego Coast Guard officials were unable to determine why the patrol boat system speed data was not recorded that night, said Eric Stolzenberg of the Office of Marine Safety

The Coast Guard boat was responding to calls from a downed sailboat, which not considered a distress situation, investigators said.

An NTSB team examining the video found the 33-foot-long boat was cruising at 42 knots at one point. San Diego Bay rules say Coast Guards boats of its size should not be operated at speeds greater than 35 knots, except in cases of “operational necessity or hot pursuit.” Those rules also say low visibility – a factor that night — calls for reduced speeds, even in an emergency response. That provision is the only speed restriction in the bay.

In the final seconds before impact, the patrol boat was traveling at least 19 knots—more than twice what NTSB says is a “safe speed” in a non-emergency situation.

Barry Strauch from the Office of Marine Safety said dark conditions, a high density of other vessels and lights reflecting on the water affected crew members.

Despite those problems, Strauch said, “Given a sufficiently slow speed the crew would have had sufficient time to have enabled them to see and avoid the Sea Ray.”

NTSB Chairman Deborah A.P. Hersman called the speeding “ironic,” noting Coast Guards patrollers would stop any boat they saw traveling that fast.

Strauch said the patrol boat’s coxswain should have known better.

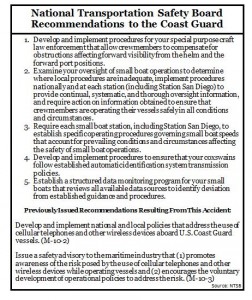

The NTSB board agreed on 15 findings and made five safety recommendations. Several factors made reaching a conclusion a challenge, though—specifically, the fact that only two of the five crew members on board agreed to talk to investigators.

In addition, investigators discovered the crew aboard the Coast Guard vessel had used personal cell phones to make calls and send text messages prior to the accident. While cell phone usage did not cause the collision, NTSB board members carefully debated the language of their findings to consider the impact of distraction.

The board reworked one finding to add: “Records indicate that the [Coast Guard] crew members used their personal cellular phones for voice calls and text messaging while underway, distracting them from effectively performing their duties as lookouts.”

Coast Guard representatives attended the meeting and released a statement on their website. “Many of the findings in the NTSB investigation confirm the Coast Guard’s own investigation and study of the accident,” said Capt. David Fish, the Coast Guard investigations chief. “We will continue to learn all that we can from their insight and thorough investigation as well as our own.”

Hersman said the board has investigated accidents with similar themes, including a 2002 accident in Biscayne Bay, Fla., in which a Coast Guard vessel collided with a passenger boat. In that case, NSTB found the coxswain failed to operate the vessel at a safe speed. Strauch said some safety recommendations in the San Diego accident recall the ones made in the Florida crash.

These collisions raise the question of whether there is a culture at the Coast Guard that allows these kinds of accidents to happen, Hersman said.

“My biggest concern,” she said, “is that there are lessons learned from this accident so we don’t repeat it.”