WASHINGTON — The U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission released recommendations this week based on lessons from Japan’s Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant disaster, declaring that events like those at Fukushima are unlikely to occur in the United States because of stringent safety measures and regulations.

The 90-day study suggested developing equipment and procedures for U.S. nuclear reactors to keep the core and spent fuel pool cool and requiring that facilities’ emergency plans address prolonged station blackouts and events involving multiple reactors.

The task force study was commissioned to see whether U.S. nuclear plants would see the same level of destruction as resulted at Fukushima Daiichi after an earthquake and tsunami hit Japan March 11.

In May, the Nuclear Energy Institute, a policy organization of the nuclear energy industry, released a report that experiences with recent natural disasters such as earthquakes in California, Hurricane Andrew in Florida and Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans have shown U.S. plants can withstand severe natural events.

In those disasters, safety systems worked as planned and operators responded effectively, the report said.

“Reactors could withstand the most severe earthquake and flooding at their site,” the Nuclear Energy Institute assessment said.

U.S. and Japanese plants use the same methods to protect nuclear fuel. Those are called “defense-in-depth” triple barriers in which nuclear fuel is cooled by multiple cooling water systems.

But the Nuclear Energy Institute report noted important differences: For U.S. facilities and operations, federal regulation is strong, plant modifications and upgrades are superior and they have better emergency readiness and response and severe accident management.

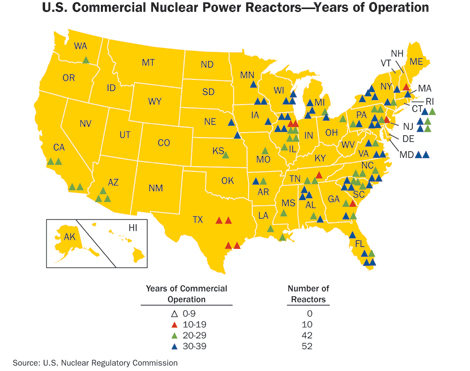

The NRC requires plants be safe during natural disasters such as earthquakes, tornadoes and floods based on the most severe historical data around the plant. Over the last 30 years, all 104 U.S. reactors have undergone a continuing cycle of evaluations, the NEI report said, and have installed upgrades to protect against loss of electrical power, pressure buildup within the containment system and hydrogen buildup, which could lead to an explosion.

The difference between the United States and Japan, NEI spokesman Mitchell Singer said, is that U.S. plants have their generators in protected structures, such as buildings with watertight doors, designed to withstand the worst natural disasters they might face depending on their geographic locations.

An official with the Federation of Electric Power Companies of Japan said it is hard to say how strict Japanese regulations of the nuclear energy industry were before the March 11 earthquake and tsunami.

“They thought they had enough countermeasures against tsunamis and earthquakes,” the official said. “They prepared well but the tsunami’s height made (the preparations) not enough.”

Since the earthquake and tsunami, the Nuclear Industry Safety Agency, the Japanese regulatory agency, has released additional safety requirements for plants, such as reinforced watertight doors to prevent water from flooding diesel generators in the plant. This requirement has been in place in U.S. plants for a while, Singer said.

The Nuclear Energy Institute says “clear differences” between American and Japanese approaches to the operation of nuclear energy plants allow U.S. plant operators to maintain safety in plants during serious events.

Regulators have different roles in the countries. The NRC is an independent agency responsible for protecting the public and the environment from radioactive contamination, as well as regulations. The Japanese regulator is part of the Ministry of Economic, Trade and Industry but may become an independent agency in the future, the Federation of Electric Power Companies spokesman said.

Licensing also is different. In the United States, reactor operators are licensed by the NRC and must re-qualify for their licenses every two years. Japanese operators are certified by an operating company instead of NISA although NISA is responsible for licensing construction of plants.

U.S. plants go through a continual evaluation process but the Federation of Electric Power Companies official said the Japanese evaluation consists of plants shutting down every 13 months for inspection and maintenance — a requirement since the first commercial reactor was built in the late 1960s.

Different people are responsible for making important decisions. Licensed operators make the decisions at U.S. plants, the Nuclear Energy Institute said. In Japan, the government plays a bigger role in important decisions. The government can order operators to shut down a plant for safety reasons. Operators can also do a voluntary shutdown but only the federal government can restart the plant, the Federation of Electric Power Companies official said.