WASHINGTON — Pink eye from a classmate. A sprained wrist from after-school basketball. Missing school because of a stomach bug.

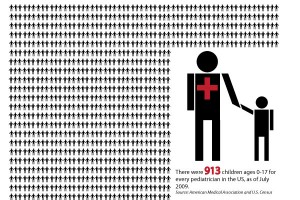

A representation of the pediatrician shortage, which could be made worse by a funding cut. (Jacqueline Klimas/MNS)

Children may have difficulty seeing a doctor in a timely matter for these and other common illnesses and injuries if funding for the Children’s Hospital Graduate Medical Education program is discontinued.

President Barack Obama’s 2012 budget proposes cutting this funding, which provides money to children’s hospitals that run a graduate medical school. The money covers part of the cost of training residents, including hospital facilities and the time doctors spend teaching.

Sens. Bob Casey, D-Penn., and Johnny Isakson, R-Ga., introduced a bill in May to reauthorize the funding through 2016. The bill, which was supposed to be discussed this week but has been pushed back because of debt talks, is set to be discussed in the Health, Education, Labor and Pensions committee on Aug. 3.

If the bill does not pass, some teaching hospitals would be forced to downsize or cut programs entirely.

“Some academic medical centers and teaching hospitals won’t be able to absorb the full expense of a full-fledged training program,” said Peter Grollman, vice president of government relations at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, which has the largest pediatric residency program in the country.

A decrease in training programs means fewer pediatricians and longer wait times for kids, which will only exacerbate the already-problematic shortage of pediatric physicians and specialists, according to Carolyn Jackson, CEO of St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children in Philadelphia.

The problem affects any of the 56 hospitals that already receive these funds nationwide, including Seattle Children’s Hospital, which serves an area already plagued by shortages. The hospital trains pediatricians to serve much of the northwest region, including Washington, Wyoming, Alaska, Montana and Idaho.

“Outside of Washington state, the other states in this region…rank among the lowest in terms of kids access to pediatric doctors,” said Hugh Ewert, director of government affairs at Seattle Children’s. “There aren’t enough pediatric doctors for all the kids that need access to healthcare right now in the region and reducing or cutting funds would only make that worse.”

Ewert worries than a reduction in funding could steer medical students towards other specialties, but Grollman notes that with all government funding on the chopping block, “academic medical centers in the adult world have a potential to lose a significant amount of their funding for their training program.”

While most programs would not disappear completely, a cut in funding would likely lead to a slow decline in the number of residencies available, said Teresa Huskey, senior director of government relations at Children’s Medical Center in Dallas.

“As access dwindles, I’m afraid we’re going to see more and more sick children having to board a plane to get the care they need,” she said.