WASHINGTON — Lawmakers from both parties are challenging the Department of Homeland Security over policies that they say impede efforts to stop imports of counterfeit electronics used in military devices.

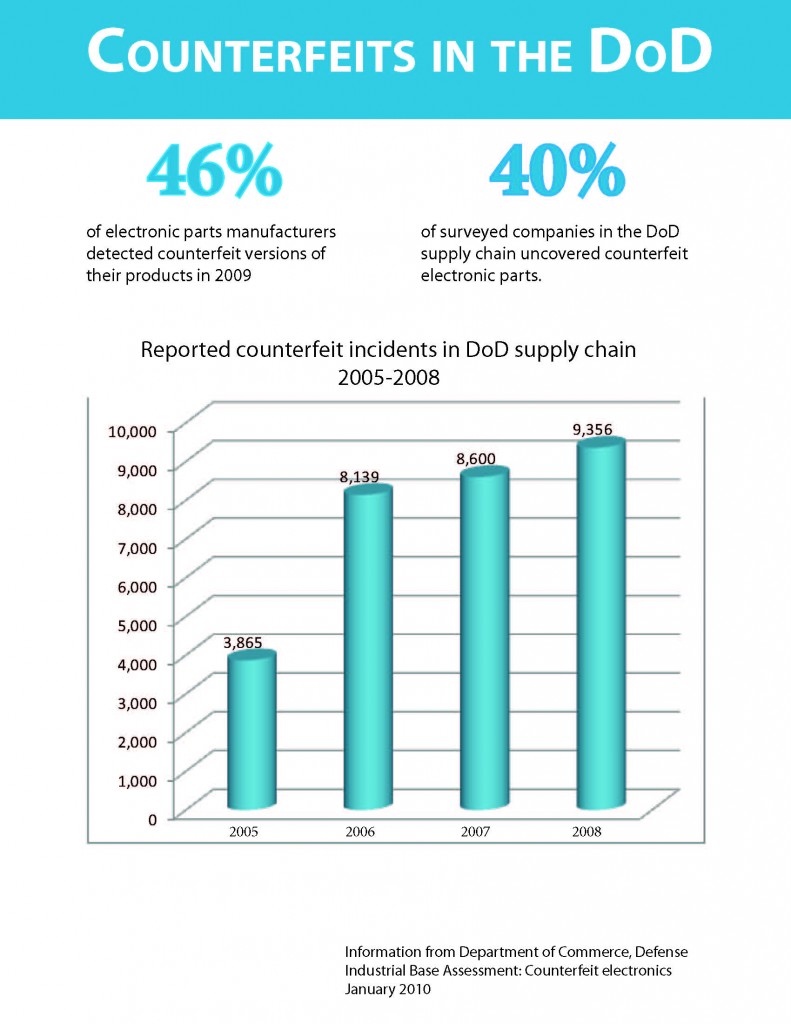

The electronic chips, which act like the brain for many electronic devices, are one of the most counterfeited parts in the Pentagon’s supply chain, according to a Commerce Department report last year. That leaves the military technology that depends on them at a great risk of failure, which experts say has huge national security implications.

“It’s very clear that there are significant numbers of (counterfeit) semiconductors that are making it through to military supply chains,” said Brian Toohey, the president of the Semiconductor Industry Association, a lobbying group. “The implications (of) that, from a reliability perspective, from a failure perspective, are very serious.”

Failing parts aren’t the only national security concern with counterfeit chips, experts say.

“The focus is not as much on quality as it is on espionage,” said Bill Chu, the department chair of software and information systems at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte.

“People are really worried about it, particularly in national security. People are really worried about building critical systems with off-the-shelf parts,” especially when the parts are built overseas.

At a hearing before a subcommittee of the House Homeland Security Committee earlier this month, Toohey testified that policies of the Treasury Department and U.S. Customs and Border Protection are handcuffing manufacturers that want to help identify counterfeit products. Until 2008, companies received complete photographs of suspected counterfeits to help identify them, but now the agencies are sending only redacted — partially blacked-out — photos, which the manufacturers say aren’t of any use, Toohey said.

After the testimony, Reps. Joe Barton, R-Texas, and John Dingell, D-Mich., and the House Homeland Security Committee wrote separately to Homeland Security Secretary Janet Napolitano and Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner asking them to explain Customs and Border Protection policies on combating counterfeits. The customs agency is part of the Homeland Security Department.

“During this hearing it was brought to our attention that Customs and Border Protection employs a policy that seems to impair the government and private sector efforts to combat intellectual property theft,” Dingell and Barton’s letter said.

The committee asked the departments to answer its letter — which requested a legal analysis and rationale behind the Treasury Department’s interpretation of the Trade Secrets Act regarding the redacted photographs — by July 27, but it has yet to receive responses.

The Homeland Security Department replied to the two congressmen’s letter but said only that its policies hadn’t changed since 2000.

“At no point has CBP altered its official position on the type or degree of information it is authorized to disclose with respect to intellectual property enforcement,” read the response by Customs and Border Protection Commissioner Alan D. Bersin.

Toohey countered that it was possible that the policy wasn’t implemented until 2008.

The Treasury Department didn’t respond to Medill’s requests for comment.

Toohey said later that discussing the issue openly at a congressional hearing wasn’t his first choice for how to handle it.

“Given the national security implications, quite frankly, we wanted to deal with it with the agencies involved,” Toohey said. “We wanted to give the agencies the chance to fix it.”

Toohey said that the FBI, Immigration and Customs Enforcement — another agency within the Homeland Security Department — and the Naval Criminal Investigative Service had worked closely with his organization on counterfeit chips.

The counterfeit chips, which composed 15 percent of all spares and replacements for the Defense Department in 2008, according to BusinessWeek magazine, are often older pieces that have been reworked with acid washes or open flames. As a result, they often can’t function properly.

The Pentagon says it doesn’t have a record of the number of counterfeits it’s recorded since 2008, but that its policy has been informed by the Commerce Department report.

“Counterfeit detection and prevention has largely been a subset of the department’s quality assurance procedures that, in the last fiscal year, barred over 200 suppliers from doing future business” with the Defense Department, Lt. Col. Melinda Morgan, a Pentagon spokeswoman, said in an email.

“The best strategy is prevention and early detection.”

More federal oversight may be coming. A Government Accountability Office investigation into Pentagon policies on counterfeits is likely in the near future, while the Senate Armed Services Committee started its own probe in March, led by Sens. Carl Levin, D-Mich., and John McCain, R-Ariz.

Toohey said the anti-counterfeit effort would require government attention “for a long time.”

“As more and more technologies use microelectronics for more and more things, and there is more and more money to be made. … I think this problem is not going away,” he said.