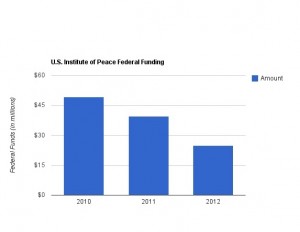

The United States Institute of Peace has been losing federal funding over the last three years, and some in Congress are trying to cut that funding all together.

WASHINGTON – The United States Institute of Peace has been a target for elimination from all federal funding by some in Congress, but institute officials say their organization ends up saving the government money.

The institute is a small organization created by Congress during the Reagan administration. Paul Hughes, director of special initiatives, calls it an independent, bipartisan conflict management center. But critics say it’s an expense the country can’t afford in tight budget times and, if needed, should be handled by the private sector.

The institute works with different government agencies such as the State Department and Defense Department to train, write doctrine and suggest policy in dealing with conflict. The focus is to decrease the need – the cost – for sending troops to wage war or resolve a conflict.

“We reduce the cost to the U.S. government,” Hughes said. “These low-cost approaches save the U.S. government gobs of money.”

But critics say these are skills the agencies should be developing already.

Rep. Jason Cheffetz, R-Utah, is one of the leading opponents. He wrote an opinion article for the Wall Street Journal on Feb. 16 with former Rep. Anthony Weiner, D-N.Y., calling on Congress to defund the institute, saying it has cost $720 million since it was created in 1985.

“It has demonstrated an ability to attract dollars from the private sector,” Cheffetz said in an interview. “I would argue that every department and agency should be working on peace. It seems to be a redundancy to have the State Department and the Department of Defense working on the same things.”

But Hughes said the institute isn’t well-known enough on Capitol Hill.

“That’s because we’re small,” he said. “I’m not sure some understand what we do with peace in our title – we’re really about conflict resolutions – our biggest supporters really are those in the Department of Defense. Those men and women know they’re the ones who pay the cost of keeping peace.”

The Army War College’s Peace Keeping and Stability Operations Institute based in Carlisle, Pa., wrote the first strategic doctrine for civilians engaged in peacebuilding missions in cooperation with the institute. It is meant to provide a roadmap for helping countries transition from conflict to peace.

“We know how to analyze conflict,” Hughes said.

For example, he cited a situation in Iraq in 2007 that the Army, the Iraqi military the State Department and U.S. Agency for International Development couldn’t fix. A mayor in a district of Baghdad wanted to bring goods in to rebuild his district’s economy, but he is Shia and all the farmers were Sunni and they refused to work with this guy, he said.

“We figured out a way to bring them together,” Hughes said. “We were able to do that because the State Department and the Department of Defense lacked the skill sets to make this happen.”

And at a cheap cost, he said.

“We’re budget dust when it comes to the federal government,” Hughes said. “We cost $30 million per year and it costs $40 million for one 40-man platoon in to be in Afghanistan for a year.”

But Cheffetz said there should be competition for this type of work and that during this economic climate, tough decisions about the budget have to be made.

“I think they’ve done some good and decent work,” he said. “I just happen to believe this should be done by the private sector. If the Department of Defense wants to partner with an agency to do this work, they should offer a contract and similar institutions and think tanks should competitively bid.”

The institute is slotted to receive a little less than $25 million in the current appropriations bill, which is in a House appropriations subcommittee. It still needs full House and Senate approval before the institute will know what the 2012 budget will look like.