WASHINGTON – Google may hold the first clues of the start of a pandemic or bioterror outbreak because people now turn to online searches before consulting a doctor when symptoms first show up.

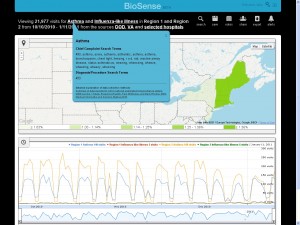

The CDC's BioSense Program has partnered with Google to provide the Dallas-Fort Worth information about public health trends in their area.

Researchers are looking at Google trends to see spikes in health-related searches that are clustered in one area or are abnormal for the time of year. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has even teamed up with Google to provide residents in the Dallas-Fort Worth area with the Public Data Explorer website so they can see health trends in their county.

“The information is particularly valuable for people who want to see or compare metro-area illness trends,” said Lou Brewer, director of Tarrant County Public Health in a statement. “Making this health information easily accessible is a key step toward educating and empowering people so they can influence the health of their community.”

The CDC created its BioSense Program, a public health surveillance system with a focus on early detection, in response to a federal mandate after 9/11. Since 2010, it has been partnering with local and state governments and private partners to provide public health data to the public.

The CDC's BioSense program gathers data from the public and private sectors to determine trending health issues.

“We look at it this type of project from all hazard perspectives,” said Dr. Taha Kass-Hout, who manages the BioSense Program and is CDC deputy director for information science. “We look at news, Google trends and pharmacy sales information to see what’s selling.”

And it’s not just all computer-based.

“It’s not just an algorithm but human beings who look at this and determine if it’s a big deal,” Kass-Hout said. “And if there is an outbreak, you might totally miss something. But then you can go back and see how it unfolded over time.”

But even if there is a spike in Google trends, sometimes public health officials or researchers aren’t quite sure what it means, said Jennifer Nuzzo, senior associate with the Center for Biosecurity at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

“You might see kind of an interesting data point, but you’re not sure what to do next,” she said. “It’s the same as looking at pharmacy sales for jumps in the purchase of certain products. Is that because there was a sale on that product?”

Kass-Hout and Nuzzo both said the health community is excited at the possibilities of using Google and other public health surveillance tools.

“These are definitely the right tools and it’s so awesome that we’re looking at behavior and how it’s changing,” Kass-Hout said.

But Nuzzo cautioned that Google trends can be analyzed, but they won’t take the place of lab results in assuming there is an outbreak.

“If you’re a public health official, it might tell you something’s going on in your city, but it doesn’t tell you what,” she said. “Typically public health officials don’t act on that type of information unless they’ve gotten some lab results back.”