WASHINGTON — Dwight Eisenhower, George Patton and Chester Nimitz: All were successful World War II military leaders — and alumni of the military’s professional education system. But there are growing concerns that looming budget cuts might hurt the system and, ultimately, the quality of the next generation of military leaders.

The worry, according to Audrey Kurth Cronin, a former war and statecraft instructor at the National War College, is that the war colleges for senior officers as well as the military education system at large will have to pick up an inequitable share of defense budget cuts.

“It’s understandable why people want to put resources toward the folks in harm’s way, because they have their lives on the line,” Cronin said. “On the other hand, what we have in the professional military education system is the strategic perspective and the future of our country. And when you cut back on that, you’re eating your seed corn.”

- Colin Powell: Army War College graduate Powell was the first African American to serve as Secretary of State. Prior to taking that position, he was the National Security Adviser to President George H.W. Bush and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff from 1989 to 1993. (Courtesy of NCS.gov)

- Alan Shepard: Shepard was the first American in space, and the fifth person to walk on the Moon. He graduated from the Naval War College in 1958. (Courtesy of NASA)

- Dwight D. Eisenhower: “Ike,” left, was The 34th president of the United States, from 1953-1961, and the Supreme Commander of Allied forces in Europe during World War Two. He’s often ranked in the top ten of most successful presidents. He graduated from the Army War College in 1928. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

- Chief of Staff of the Army, General Ray Odierno, briefs the press at the Pentagon in Washington D.C. on January 27, 2012. Odierno is the current Chief of Staff of the Army and served as the commanding general in Iraq. He studied national security and strategy at the Naval War College.(courtesy DOD; photo by Erin A. Kirk-Cuomo)

- Alexander Haig: Haig was the secretary of State for President Ronald Reagan. He fought in Korea and Vietnam, and attended the Army War College. (Courtesy of the Nixon Library)

- Anthony McAuliffe: When offered a chance to surrender during the 1943 Battle of the Bulge, where his men were surrounded by the German army and trapped in the town of Bastogne, France, McAuliffe famously offered a one-word reply: “Nuts!” He graduated from the Army War College in 1940. (Courtesy of the National Archives)

- George S. Patton: Patton, a graduate of the Army War College, was best known for his leadership as a general in WWII and his gruff, sometimes-controversial style. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

- Leslie Groves: Groves, Army War College class of 1939, oversaw the construction of the Pentagon, and earlier, the Manhattan Project that developed the atomic bomb.

- David H. Petraeus: U.S. Army Gen. David H. Petraeus delivers remarks at his retirement ceremony and Armed Forces Farewell for Joint Base Meyer-Henderson Hall, Va., August 31, 2011. Before he was the general in charge of Central Command, the International Security Assistance Force in Afghanistan or director of the CIA, Petraeus was a graduate of the Army Command and General Staff College, and later Princeton University. (Courtesy of DOD; photo by Mass Communication Specialist 1st Class Chad J. McNeeley)

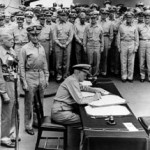

- Chester W. Nimitz: Nimitz, who attended the Naval War College, was the commander of the Pacific Fleet and commander of United States forces in the Pacific Ocean during WWII. Shown here signing the Japanese instrument of surrender aboard the USS Missouri.(Courtesy United States Navy)

Officers begin in the professional military education system primarily focusing on their branch and specialty. As they ascend in rank and responsibility, their studies widen in scope, leading to the senior service colleges of each branch. For the top echelon of officers, that usually includes a final stop at the war colleges.

Each of the war colleges is slightly different, but all usually enroll top lieutenant colonels or colonels — captains and commanders for the Navy — and varying numbers of civilians from all over government.

The war colleges focus on strategic decision-making at the 30,000-foot level. Students go through 10-month programs and, upon completion, earn master’s degrees.

The expectation is that many of these students, who are all at the top of their peer groups, will go on to be senior leaders in their organizations

‘A lot of punch for not a lot of money’

The Defense Department’s operation and maintenance budget for military professional development programs, which includes military education, was about $1.1 billion that year. The 2011 defense budget was $528.2 billion, and the White House estimated the 2012 budget at $530 billion. The Pentagon has proposed a cut of 2.5 percent for fiscal 2013, to $525 billion, and a combined total of $487 billion in reduced spending over the next decade.

Tom Nichols, a professor of national security at the Naval War College, said all government agencies are feeling the pressure to slim down, and the professional military education system is no exception — nor should it be. However, he added, the system provides a lot of value for relatively little money.

“Military education is a lot like foreign aid: Everybody thinks there’s a lot of it and it’s really expensive,” he said. “But it’s not true. The fact of the matter is, the war colleges are cheap.”

Military education at this level does — in half the time and at a lower price — what civilian schools are doing, he said, and it’s more a more efficient education because of the war colleges’ specific military focus.

According to the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, the cost of one student’s course of study in 2012 ranges from $57,000 at the Naval War College to $160,000 at the Army War College.

“If you were to take the officers and send them to civilian schools to try to get them the equivalent amount of education in national security affairs,” he said, “they’d have to go to school a lot longer and pay a lot more to do it. We deliver a lot of punch for not a lot of money.”

Uncertainty in 2013

Congress is debating the defense budget for 2013, and the extent of possible cuts isn’t clear. The National War College’s budget estimates for 2013 show an 11 percent decrease from 2012’s budget of more than $7 million.

Bob Mahoney, dean of the Marine Corps War College, said the commandant of the Marine Corps has stated that military education is a high priority. Officials at the Army, Navy and Air Force’s war colleges didn’t want to guess at whether they’d be taking cuts or what they’d be.

“Everyone’s scared,” Mahoney said. “But we have no idea exactly what’s going to happen.”

George Reed is a dean at the University of San Diego and former instructor and student at the Army War College. “Almost never in my civilian academic role are we called upon to justify the existence and purpose of the institution that I’m teaching in,” he said. “But that happened with regularity at the war colleges.”

Meanwhile, professional military education lost one of its most vocal advocates on Capitol Hill when Ike Skelton, former congressman from Missouri, lost his seat in 2010. Skelton led the last in-depth review of professional military education in 1989, and without him, said former National War College instructor and student Dave Maxwell, PME doesn’t have much of a constituency in Congress.

Maxwell, a retired Army Special Forces colonel, called Skelton the “lone voice in the wilderness” who reminded others that the military has to invest in people, too.

“We don’t cause jobs to be made in factories,” Maxwell said. “When decisions are being made on what to resource, the services and Congress focus on weapons systems.”

When the position of president of the National Defense University, which includes the National War College, was reduced by one rank recently, Maxwell said he and others considered it a troubling sign. Vice Adm. Ann Rondeau held the position until she retired in April, and will be replaced by Army Maj. Gen. Gregg Martin.

“From a perception standpoint, that just gives the appearance that there is a reduced priority on education,” Maxwell said.

The office of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, which chooses the NDU president, did not immediately respond to questions about the rank reduction, but it’s conceivable the position was changed to counter “brass creep,” or the proliferation of general officers and their accompanying large paychecks.

Setting priorities

The notion that NDU will somehow lose standing is overblown, said Ben Freeman, who investigates the issue of brass creep for the Project on Government Oversight. It’s more about internal military politics than actual effectiveness, he said. As for the National Defense University, Freeman said he found a “wonderful culture” upon a visit there.

“Whether [the president] was a three-star or a two-star or a no-star, it’s not going to change that,” he said.

The question that keeps arising, Nichols said, is whether there’s an adequate “return on investment,” which he said is virtually unanswerable for any educational institution.

“At some point, you can’t turn education into a completely functional, instrumental, occupational model,” he said. “You have to accept that you plan things that are going to come to fruition later. And when budgets get tight, people want to know what you’re doing to kill the enemy today.”

Joan Johnson-Freese, another professor at the Naval War College, said she’s concerned about what cuts might mean in a world were American officers face increasingly complex situations and must act as diplomats and social workers, as well as fight.

“When decisions are being made in Washington about whether the United States should engage militarily abroad, or how to approach a challenge abroad, we have to have military voices at the table to offer their opinions,” she said. “Without this kind of education, strategic military education, they’ll be left out.”