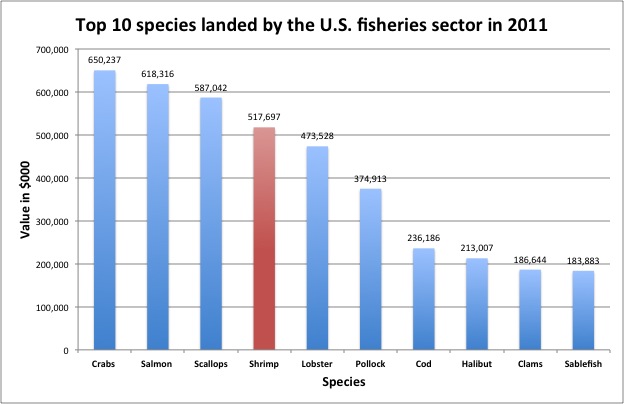

Image Source: Creative CommonsOn average, Americans consumed 4.2 pounds of shrimp per capita in 2011, according to the National Marine Fisheries Service.

Image Source: Creative CommonsOn average, Americans consumed 4.2 pounds of shrimp per capita in 2011, according to the National Marine Fisheries Service.

WASHINGTON — Domestic shrimp producers find out Tuesday whether they will be one step closer to getting relief from subsidized imports that have taken over about 75 percent of the U.S. market for the shellfish and, the shrimpers say, cost them billions of dollars in lost revenue.

The U.S. International Trade Commission will hold its Aug. 13 hearing for the final phase of a contervailing duty investigation of frozen warmwater shrimp imports from seven countries: China, India, Thailand, Malaysia, Vietnam, Indonesia and Ecuador.

It will decide whether the subsidized shrimp imports are causing “material injury” to domestic producers. The seven countries exported more than 984 million pounds of shrimp worth nearly $4.3 billion in 2011.

Overall, shrimp consumption in the U.S. is increasing and Gulf Coast processors are working to stay competitive in a growing market. In 2011, the U.S. consumed 4.7 billion pounds of seafood, surpassing Japan to become the second largest consumer after China.

The Coalition of Gulf Shrimp Industries first filed a petition in December 2012 claiming that the U.S. shrimp industry is being hurt by an increase in subsidized shrimp imports. The coalition represents shrimp processors from Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Texas and Florida that make up 94 percent of domestic shrimp production.

According to the coalition, the seven countries account for 89 percent of U.S. shrimp imports and three quarters of the overall domestic market. As a result, subsidies provided by the countries’ governments greatly affect the pricing of shrimp in the U.S.

“The prices are so low that if you do not catch in great volumes, you can pretty much tie up your boat,” said Kim Chauvin, owner of Louisiana-based processor Bluewater Shrimp Co. “Last year we lost about 30 different customers because of pricing and that makes or breaks your year.”

The Tariff Act of 1930, a law that was originally introduced to protect farmers from agricultural imports, allows U.S. industries to “petition the government for relief from imports that benefit from subsidies provided through foreign government programs,” according to the USITC.

Patrick Macrory, director of the International Trade Law Center at the International Law Institute, said, “Basically a subsidy is anything the government is giving that is below market value … very often it is a low-interest loan.”

The Department of Commerce launched an investigation in May to determine if there was sufficient evidence to support the coalition’s claim that the seven countries were subsidizing their shrimp industries.

During the preliminary phase, the department found that all countries except for Indonesia and Ecuador gave countervailable subsidies to support the shrimp production industry.

Using information provided by industry officials in response to Commerce Department questionnaires, a preliminary report found that Ecuador and Indonesia both received subsidy rates of less than 2 percent.

China was found to have subsidy rates of 5.76 percent but one Malaysian company was found to have received subsidy rates of 62.74 percent because it didn’t respond to the survey so the Commerce Department gave it the maximum rate possible.

“So I think Malaysia will be out of the market after this,” Macrory said.

The Commerce Department’s investigation has been running concurrently with the USITC’s investigation to determine whether the subsidies are causing material injury to U.S. producers.

For the final verdict, an affirmative decision calling for countervailing duties will need to be reached by both the USITC and the Commerce Department before any penalties can be applied, according to Peg O’Laughlin, a spokeswoman for the International Trade Commission.

The final phase of the International Trade Commission’s investigation began in April and follows a 45-day preliminary phase that found there was reasonable indication that the shrimp industry was being materially injured by the subsidized imports.

The commission’s preliminary investigations typically explore relevant economic data ranging from domestic sales, output, market share, employment and profit. After collecting quarterly pricing data from a variety of domestic processors and foreign importers, the commission found that frozen shrimp imports undersold domestic product in 138 separate cases, which represented nearly 40 percent of the total comparisons made.

While domestic indicators showed some positive and negative trends in the U.S. shrimp market, the commission ultimately concluded “the cumulated subject imports have had a significant adverse impact on the domestic industry.”

“Any unfair trade harms the U.S. shrimp industry – getting rid of unfair trade is very important,” said John Williams, executive director of the Southern Shrimp Alliance. “But the industry understands and appreciates that you can’t just say that unfair trade is occurring, you have to prove it.”

The USITC will need to find firm evidence during the final phase to prove actual harm to domestic shrimp producers in order to give an affirmative verdict. The final phase of the USITC’s investigation is expected to conclude in October.

If an affirmative verdict is reached, a countervailing duty equal to the amount of subsidies that a country is found to be giving will be imposed.

“The idea of these laws is to counteract the effect of subsidy by raising prices in the U.S.,” said Macrory. “The assumption is that because these countries get a subsidy, they are able to sell more cheaply in the U.S. and this will counteract that.”