Based on whether they are deemed “exempt” or “excepted,” federal agencies will either retain or furlough a number of their employees as a result of the shutdown. Katie Peralta /MEDILL

WASHINGTON — Tens of thousands of federal employees deemed “non-essential” mingled with the usual Washington lunch crowds Tuesday as they started their furloughs, the result of the government shutdown. But first they spent the morning completing furlough-related duties.

“We had been prepared for what we had to do for the shutdown,” said Jeffrey Page, 34, an attorney with the Environmental Protection Agency for six years.

Whether they were headed to lunch, to run errands or home for chores, some of the “non-essential” government workers found other jobs they deemed personally essential.

“I’m going to mow the lawn,” said Robert Daly, a furloughed Woodrow Wilson Center employee who was crossing the Federal Plaza on his way home Tuesday.

“It’s a bizarre word to use. We are all essential I think,” said a 53-year old Health and Human Services furloughed employee who asked to remain anonymous. “The piece that is missing is we are not essential for operations during shutdown.”

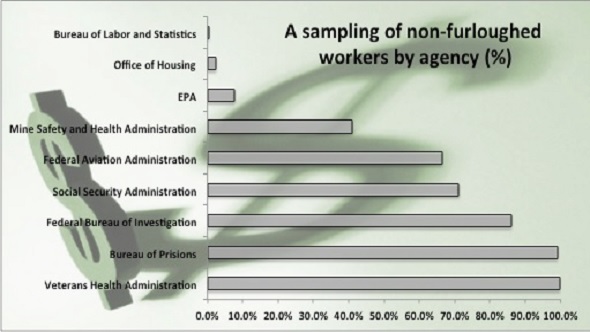

Based on guidance from individual government agencies, employees continued to work if they were “exempt” or “excepted” from the furlough, making their role “essential,” a divisive but decisive concept.

According to the Office of Personnel Management, an employee is “excepted” if he or she performs work involving the safety of human life. Employees are “exempted” from the furlough if they are not affected by a lapse in appropriations. Non-essential workers neither exempted nor excepted are furloughed if the federal government isn’t funded by Congress.

Determining who is non-essential is based on the Antideficiency, Act, which contains language that some say is open to interpretation. According to the act, federal agency heads decided which employees stay and would leave in their shutdown plans.

Some of the employees perform many of the nation’s basic services like food inspection and Social Security claims reviews, a reality that concerns American citizens and policy experts.

“There are all sorts of important functions that will be suspended ,” said Phillip Wallach, a fellow in governance studies at the Brookings Institution in Washington.

“We will see an erosion of services every day,” said J. David Cox, president of the American Federation of Government Employees at the AFL-CIO.

In addition to the loss of federal services, government workers’ uncertainty over whether they will get backpay when the shutdown ends could spread to the broader economy, said Wallach.

Dr. Matthew Canzoneri, an economics professor at Georgetown University, said economic uncertainty could both cause U.S. consumers to act more cautiously and could cause foreign investors to lose confidence in investing in U.S. debt.

But for the people who left the early office today, fiscal concerns are more immediate.

“I’m disappointed with how they are behaving on the hill. I am a lawyer and I have a lot of debt from law school,” said Page, the EPA attorney.

Added Daley, the Woodrow Wilson Center worker: “It’s going to start to bite pretty hard if it goes beyond a week.”