WASHINGTON — If you ask Randall Reeder, retired Ohio State University Extension agricultural engineer, what he thinks about no-till farming, it’s simple.

“If all the land farmed around the world was in no-till, we could probably reverse climate change,” Reeder says.

Well, maybe not that simple. Timothy Crews, a researcher at the Salina, Kansas Land Institute, says without accurate tests of carbon deposits deep below the soil’s surface, it’s hard to say with any certainty.

Reeder’s argument is pretty basic, and he has one that Crews agrees with: tilling farm land has increased carbon dioxide emissions, contributing to global warming. If farmers could keep the carbon in the ground, they would be able to decrease carbon dioxide emissions on farms.

If you’ve ever been around a farm in the springtime, you might have noticed clouds of dust billowing up behind the big John Deere plows. That’s tilling, breaking up the land and the ground cover before the farmer plants his crop for the season.

A farmer tilling his field. Photo courtesy of U.S. Government.

As the soil is broken up, organic content or carbon is released from under the soil, and raised to its surface. When bacteria and fungi at the surface feed on the carbon, they release nutrients which crops use to grow.

Crews, lead researcher at the agricultural research institute in Kansas, said early farmers started to use tilling when they noticed it increased their crop yields.

The only problem with this massive release of carbon to the soil’s surface?

When it’s exposed to the oxygen in the atmosphere, it becomes carbon dioxide gas, a greenhouse gas that is a contributing factor in the planet’s warming, and also, some scientists maintain, extreme weather events, Reeder says.

No-till advocates favor a simpler approach, one they say would decrease carbon emissions.

A farmer using no-till simply “plants during the spring, sprays sometimes twice with herbicide, applies fertilizer dropped on the surface or injected in a slot, and then harvests,” Reeder says.

A no-till farm. Photo courtesy of the USDA.

He doesn’t even need the plow anymore.

To increase the yield of a no-till system, a farmer might need to plant a cover crop like cereal rye or sunflowers. These cover crops improve soil health by depositing carbon back into the soil. Benefits of cover crops, which might include “adding nitrogen, breaking up compacted soils, reducing soil erosion, and adding organic matter to the soil,” could apply to any field Reeder says.

Sunflowers and cereal rye are good cover crops in a no-till system. Photo courtesy of USDA.

“No-till farming adds organic matter (carbon) to the soil. Tillage removes carbon from the soil and releases into the air as carbon dioxide,”Reeder says.

Along with putting carbon back into the ground, Jerry Hatfield, plant physiologist at the USDA says no-till farming decreases the evaporation in the soil system that’s common after extreme droughts or flooding.

The ground cover that no-till farming leave behind makes it easier for rain to penetrate the soil, even during the heavy storm that have become more common. Evidence of this increased moisture can be found in the roots of no-till plants: they’re shorter and located closer to the surface where the moisture is.

Hatfield says there are also some serious economic benefits to no-till.

He estimates farmers who use no-till grow about 15 to 30 bushels more than the average yield throughout the country. He also said no-till farmers tend to save about $30 per acre, simply because they don’t have to pay the input and labor costs associated with tilling a field.

In Central Ohio, Gene Branstool was a no-till farmer for 38 years on his spread near the rolling foothills of the Appalachian Mountains. He credits no-till with increasing his yield as it upped the organic content of the soil without disturbing earthworms, crucial to the carbon cycle in the soil.

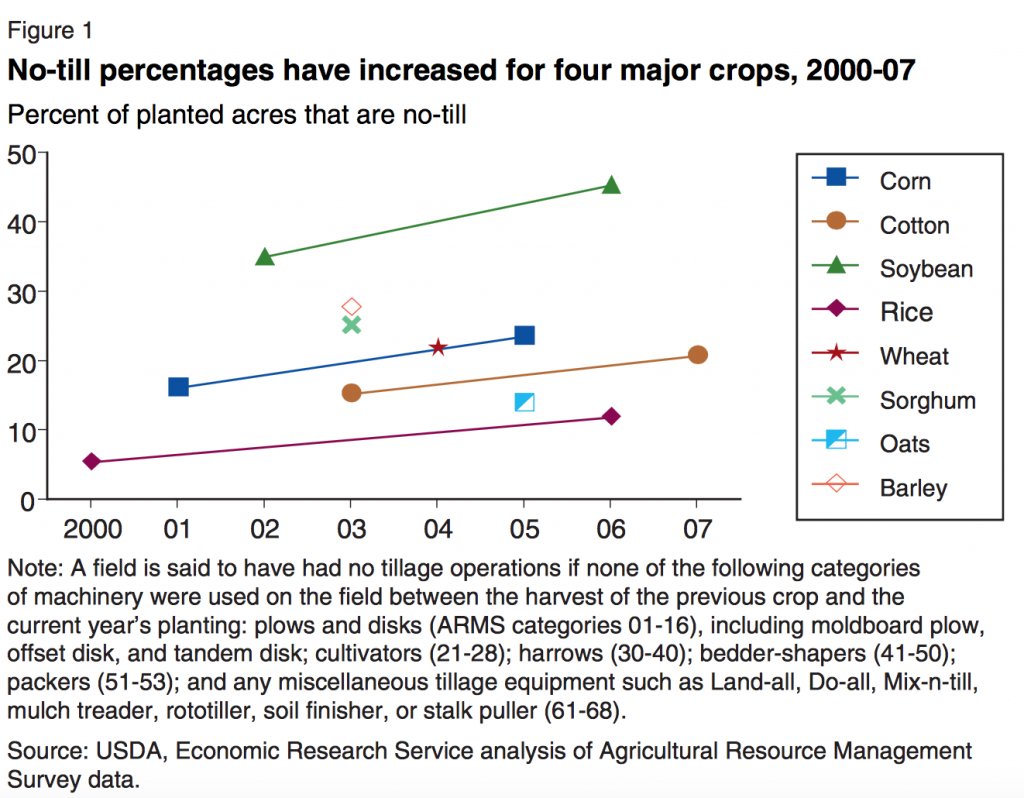

And he’s not alone: according to the USDA, over 35 percent of U.S. farms were no-till in 2009. That’s about 88 million acres of farmland.

No-till systems are increasing in the U.S. Chart courtesy of USDA’s “No-Till Farming is a Growing Practice.”

But Jodi DeJong-Hughes of the University of Minnesota Tillage Program, warned that no-till isn’t for everyone. It should only be used on a field-by-field basis.

“Not one system will fit everybody and there’s crops or soil conditions or topography that are a better fit for less tillage, or a little bit more,” De-Jong Hughes said in a phone interview.

In other words, if a farmer already has an unproductive field or if he’s planting a corn-corn rotation on clay-like soil at Purdue University says.

Another caution: in terms of herbicide use, both DeJong-Hughes and Vyn said most no-till farmers will also need to use more herbicide to control ground cover and weeds — anywhere from one to two more passes beyond what farmers who till their fields need.

Crews, of the Land Institute, said that when done right no-till farmers can use cover crops to compete with weeds. But eventually, most no-till farmers will need to use additional herbicide to get rid of last year’s cover crop or weeds that tilling would have taken care of.

So in general, the benefits of no-till farming — curbing soil erosion and rebuilding soil organic matter — are pretty well known, he said.

But the dependence of no-till farmers on herbicides, many of which are known carcinogens, and the leakage of these herbicides from fields, will be problematic for no-till farms in the future, says Crews.