WASHINGTON – Hungarian citizens will head to the polls on April 8, but Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has little cause for concern. The rest of Europe, however, might have reason to worry.

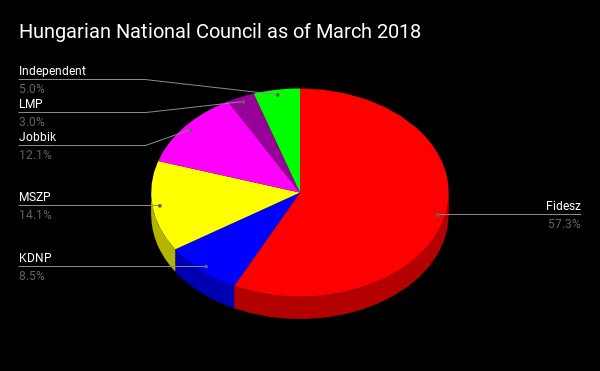

Orbán — and his party, the Alliance of Young Democrats, or Fidesz —have become a symbol of success for far-right parties in Europe. In a recent poll, the Fidesz coalition enjoys support from around 30 percent of voters; no other party clears 20 percent, according to Reuters. The party holds 114 of 199 seats in the National Assembly, Hungary’s parliament, and is known throughout the continent for its vehement opposition to immigration, particularly when those immigrants are Muslim.

“There are those who want to take our country from us… They want us to hand it over to foreigners coming from other continents, who do not speak our language, who do not respect our culture, our laws or our way of life,” Orbán said in a recent speech commemorating the 1848 Hungarian Revolution. “The situation is that those who do not halt immigration at their borders are lost: slowly but surely they are consumed.”

Hungary’s largest opposition party is even further to the right: the second-largest party, Jobbik, has long advocated for ideas that are now common among far-right groups the world over, including a border wall and a single-race ethnostate.

Whatever the exact results of next month’s election, it seems quite likely that Hungary will continue on its existing rightward trajectory. And as right-wing parties like Fidesz and Jobbik gain traction throughout Europe, many other countries seem likely to follow the same path.

Just a few years ago, this phenomenon would have been unthinkable.

But as the United States adapts to the enormous political changes wrought by the candidacy and victory of President Donald Trump, Europe, too, is undergoing an enormous sociopolitical transition.

The influx of refugees from the Middle East and North Africa has changed the landscape of many European countries; it has also brought to life an extreme right-wing ideology that most thought had ended for good.

Each of these far-right parties that seem to be gaining in popularity share a few common threads, according to comparative politics expert and American University professor Stephen Silvia: “[Being] anti-Muslim immigrants is a common theme that’s in all of them. A second one would be anti-elite, particularly the political elite… and then the third thing that you can see in all of them is an anti-European Union position. Sometimes it will focus on the Euro, sometimes it will be broader.”

These parties tell locals a similar story: that immigrants are coming to dilute or even destroy their culture. The key tenets of this story are “the economic migrant who comes to Europe because he is too lazy to work and seeks to be funded by the state,” and “the story that the political elites and their lax immigration policies would open the doors to Islamic fundamentalism and terrorism, exposing their citizens to the risk of becoming the victims of terrorist attacks,” says Mona Krewel, an expert on European politics at Cornell University.

In short, these parties warn prospective voters of a coming influx of dangerous immigrants, from whom political elites are unable or unwilling protect them.

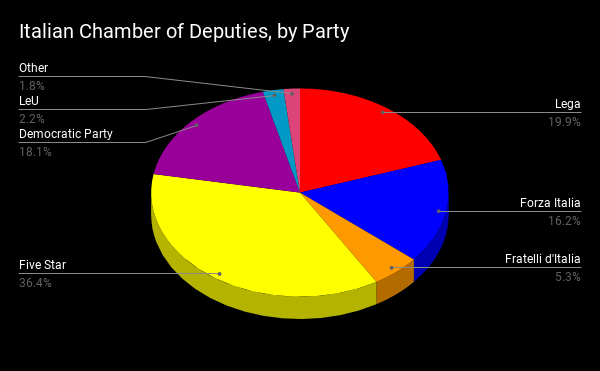

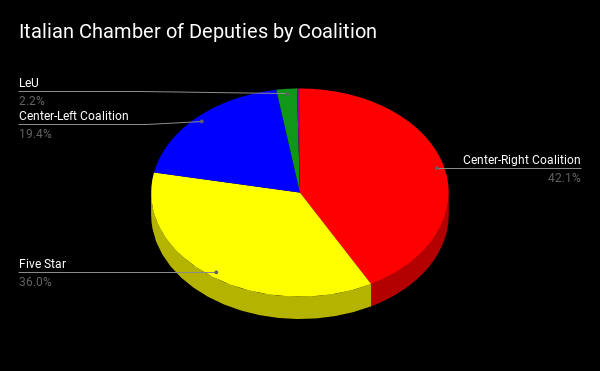

In many cases, that story appear to be gaining traction among the public. One of the most recent examples is the March 2018 Italian parliamentary election, in which far-right group Lega Nord (sometimes known simply as “Lega”) made huge gains, especially in the Chamber of Deputies, Italy’s lower parliamentary house. Although the party did not win its own plurality, Lega was part of the center-right coalition, the group that won the largest overall share of the vote. Within that coalition, Lega was the largest group.

In the run-up to those elections, Lega rebranded itself as the anti-immigration party, adopting the mantra “Italians First” and expanding its reach from just the north — the “Nord” of its original name — to across the country, fielding parliamentary candidates throughout Italy.

Why has Lega been so successful? “Italy has one of the weakest economies of the Eurozone and has received hundreds of thousands of migrants and asylum-seekers in a very short period of time between 2015-2017,” says Filippo Trevisan, an American University professor who researches the role of political communication in European elections. “Politicians such as [Lega leader Matteo] Salvini… regularly accuse migrants of being the undeserving beneficiaries of resources that instead should go to Italian families in need.”

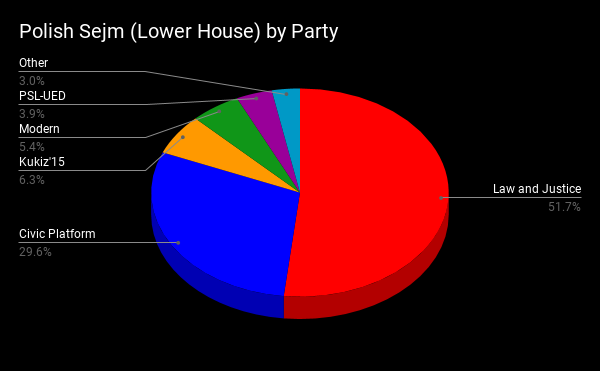

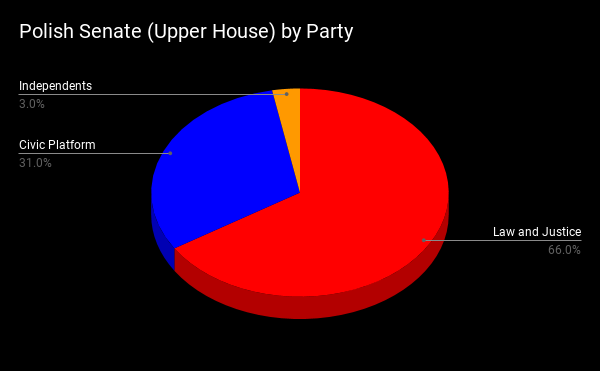

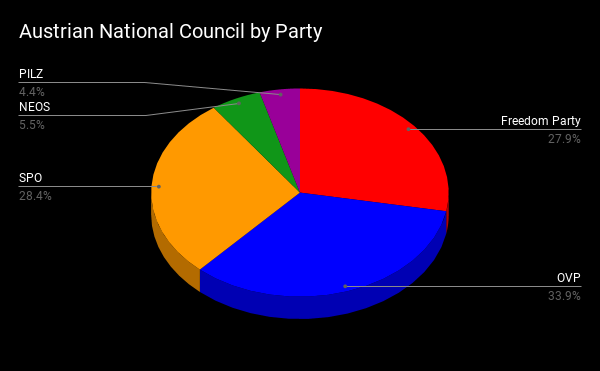

It is a common story in today’s Europe. Poland’s right-wing Law and Justice party enjoys majorities of 51 and 66 percent, respectively, in each of its houses of Congress. Austria’s Freedom Party secured enough votes to promote one of its members, Heinz-Christian Strache, to a top position in a coalition government.

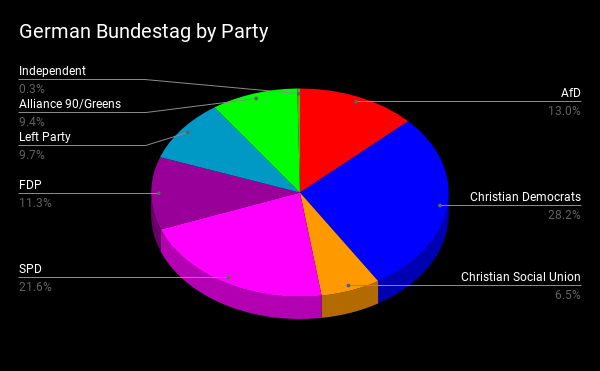

In September 2017, the AfD party, whose name translates to Alternative for Germany, won nearly 14 percent of seats in the Bundestag, the German parliament. AfD is now the third largest party in that parliament, despite being founded only four years before the election. Even in France, where the anti-immigrant Front National party lost the 2017 presidential election, its candidate, Marine Le Pen, still won over 10 million votes.

But there are signs that far-right anti-immigrant ideology may not be the inevitable future of European politics. In addition to Le Pen’s presidential failure, for example, the Front National achieved only eight seats in the French National Assembly.

The United Kingdom’s UK Independence Party virtually dissolved after the much-maligned Brexit vote. By the end of 2016, 42 percent of UKIP voters were telling pollsters they planned to vote for another party, according to the British Election Study,

That dissolution could perhaps be regarded as acceptance of success on the single issue that motivated them; however, UKIP never achieved significant representation within parliament. The parties that do have significant representation in the Houses of Lords and Commons, even the right-leaning ones, are much closer to the center.

Even in Hungary, there are signs that the right wing’s hold may not be impenetrable. A recent mayoral election in Hodmezovasarhely surprised the country: although the southern Hungarian city is regarded as a Fidesz stronghold — and is even Orbán’s own hometown — an opposition candidate, Peter Marki-Zay, was elected mayor.

“In this city, there’s demand for liberty,” Marki-Zay said in his victory speech, “for democracy, for the rule of law, for a market-based economy and for a commitment to Europe.”