In the days prior to Wisconsin’s coronavirus-induced lockdown, Rick Seppa was greeted each morning by a medley of 1980s rock music performed by his band students at Washburn High School in northern Wisconsin.

The medley included music from Michael Jackson and Bon Jovi and was to be performed at the band’s spring concert, now canceled.

Seppa, who has worked as an educator for more than three decades, is among the thousands of teachers across Wisconsin adjusting to online instruction amid the COVID-19 pandemic. He also is among those whose rural schools face unique challenges to online teaching.

“I would have never, ever imagined that I’d ever have had to deal with something like this current situation,” Seppa said. “This is a struggle.”

Though Seppa can gather his students together on a video conference, they can’t all play together because audio transmission over the internet is difficult to sync up via services like Zoom.

What’s more, one in six of his students don’t have access to reliable internet at home, he said. He added that infrastructure, not cost, is the barrier to high-speed internet for most of his students — something that is commonplace in rural Wisconsin.

In 2019, roughly 486,000 Wisconsinites did not have broadband access, according to a Federal Communications Commission report. The FCC defines broadband as an internet connection with 25 megabit per second download speeds and three megabit per second upload speeds.

A survey from the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction found that students in small school districts — many of which are located in more rural areas — often lack access to the internet because of where they live. Among school districts with fewer than 2,000 students, 28% reported that at least half of their students lacked access to reliable internet because of where they live. That figure is just 8.7% among districts with 2,000 or more students.

Wisconsin’s U.S. senators and a new congressman from northern Wisconsin have all pledged to push to expand broadband access, but Republicans, who control the Senate and White House, provided little to no details on how they plan to accomplish that.

Special delivery

Washburn School District has a one-to-one technology policy, meaning every student is provided access to a tablet or laptop. However, those devices aren’t helpful for schoolwork if students can’t get online to access assignments. Instead, Seppa said, teachers have reverted to printing out and collating materials during the pandemic to deliver to students, sometimes as far as 30 miles away.

“I’m kind of like inventing the wheel every day,” Seppa said.

A little over 100 miles southwest of Washburn, near the Minnesota-Wisconsin border, students in Frederic face similar challenges to getting online.

“We’re not just providing solely online learning because we can’t,” said Megan Challoner, principal of Frederic Elementary School. “According to a survey we sent out … 15% of our families don’t have access to stable internet.”

Challoner said her teaching staff also has been distributing printed materials to help students stay engaged during the pandemic.

The hot spots

Frederic schools, which also have a one-to-one technology policy, distributed hot-spot devices to students, Challoner said. She said the system only got off the ground recently because of increased demand for hot spots as the nationwide shutdown made it hard to find the internet-enabling devices.

Additionally, Challoner said the school installed a “strong wireless router” to cover the facility’s parking lot, where students and their families can access the internet from their vehicles. The only drawback, Challoner said, “is that some of our families live 20 miles away from the school.”

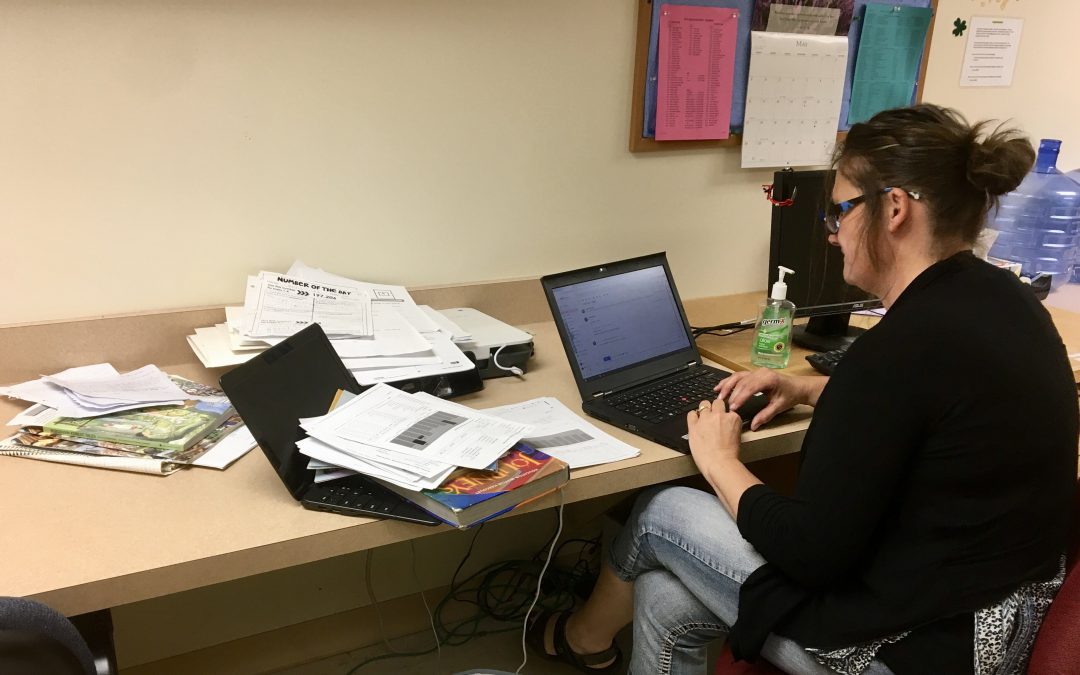

Some members of the school’s teaching staff lack reliable internet at home so they’ve been teaching online from their classrooms while abiding by social distancing guidelines, she said.

Unstable links

Goodman-Armstrong Creek School District in Wisconsin’s northeastern-most corner also has worked to create Wi-Fi hotspots, according to Superintendent Allison Space.

Space said Goodman-Armstrong Creek is the state’s second-smallest school district. It served just 101 students during the 2019-20 academic year, according to DPI data.

“I would say probably a heavy 40% (of our students) do not have access to reliable internet,” Space said.

For many of them, she said, even when they get online, their connection is unstable and often through a cellphone.

Space said the district partnered with a local internet service provider to put up four Wi-Fi towers in the communities the district serves. She explained that students, similar to those in Frederic, can travel to the locations and get online. The towers will be available until the school year starts in the fall, Space said.

Voices in Congress

Additional federal support for rural schools remains unclear. At a recent congressional hearing, U.S. Sen. Tammy Baldwin, D-Madison, said “the COVID-19 crisis has laid bare the reality of how needed” broadband is in daily life.

Baldwin was among a series of lawmakers who recently introduced a $4 billion bill that would provide funding for Wi-Fi hotspots, modems, routers and internet-connected devices to schools and libraries to help people get online during the pandemic. Schools that receive funding through the bill would be able to purchase and distribute devices for use during the pandemic.

The bill does not include funding to expand broadband infrastructure, which is needed for more rural Wisconsinites to be able to access high-speed internet.

In a recent statement, U.S. Sen. Ron Johnson, R-Oshkosh, said he is “continuing to work with my colleagues on broadband proposals targeted to help those who need it most, during the pandemic and beyond.”

U.S. Rep. Tom Tiffany, R-Minocqua, who was sworn in recently to represent the district encompassing Frederic and Washburn, said during his campaign that expanding broadband would be a high priority for him in Washington. His office did not respond to requests for details about the congressman’s plans to expand broadband.

The House Democrats’ new $3 trillion emergency relief bill, which was approved by the chamber last week, includes $1.5 billion to support the same efforts as Baldwin’s bill. However, the Republican-controlled Senate is unlikely to pass the legislation.