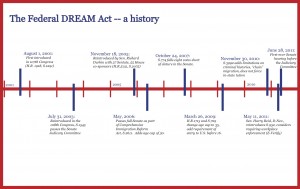

Versions of the DREAM Act have been introduced multiple times in Congress in the past decade. Click to enlarge. (Gabrielle Levy/MNS)

W

ASHINGTON–Ten years after it was first introduced in Congress, the DREAM Act–the federal bill promoting a path to citizenship for undocumented youth through education or military service—received its first Senate hearing this week.

Education Secretary Arne Duncan and Homeland Security Secretary Janet Napolitano appeared before the Senate Judiciary Committee Tuesday to represent the Obama administration’s strong support of the bill. A crowd of hundreds—many undocumented students calling themselves “DREAMers” and dressed in ceremonial graduation caps and gowns—turned out to support of the legislation.

Iowa Democratic Sen. Tom Harkin, a co-sponsor of the bill, said in a statement that it is a way for “children who are in America not due to their own action but those of their parents to reach their potential.”

But Iowa Sen. Chuck Grassley, the top Republican on the Judiciary Committee, told the hearing that he had concerns about parts of the bill, especially that it might lead to fraud and abuse of the immigration system and that it would encourage further illegal immigration by appearing to grant amnesty to some.

Sen. Richard Durbin, D-Ill., who chaired the hearing and is the lead sponsor of the legislation, introduced several audience members who would be eligible for conditional permanent resident status under the bill’s provisions.

“These DREAMers would happily go back to the end of any line and wait for their citizenship,” Durbin said, calling the issue “one of the most compelling human rights issues in our time.”

The Development, Relieve and Education for Alien Minors—or DREAM—Act would offer the chance of citizenship to undocumented immigrants under the age of 35 who were brought to the United States before the age of 16 and who have been in the country for at least five years.

After receiving conditional lawful permanent residency, individuals would have to complete at least two years of higher education or military service, pass background checks and demonstrate “good moral character” in order to apply for citizenship.

“This is dangerous not only for the men and women who patrol our boundaries, but for the immigrants themselves,” Grassley said in a statement submitted to the record. “It is not unusual for those wanting a better life to justify their illegal behavior but it just that: illegal.”

In his statement and questions at the hearing, Grassley also pressed for clarifying the bill’s language because many illegal immigrants do not have verifiable documentation on their age or when they entered the United States—information necessary to determine a person’s eligibility for the DREAM Act.

Napolitano sought to address some of the security concerns by distinguishing between DREAM Act-eligible people and criminal aliens.

“Passage of the DREAM Act would allow us to focus even more attention on true security threats by providing a firm but fair way for individuals brought into our country as children—through no fault of their own—to obtain legal status by pursuing higher education, or by serving in the U.S. armed forces for the country where they have grown up and which they consider their home,” Napolitano said.

Maria Alvarez, 22, a resident of Marshalltown, came to the United States from Mexico when she was 4. She said she graduated from high school and enrolled in community college, only to drop out to find work because she couldn’t qualify for in-state tuition as an undocumented immigrant.

“It’s so frustrating because so many people that you see are smart, who want to continue their education,” Alvarez said. “I want to go to school so bad, and I want to be able to give my family a good name.”

Alvarez is one of an estimated 55,000 to 85,000 undocumented immigrants in Iowa, according to the Department of Homeland Security’s estimate from 2009. The Iowa state Department of Education estimates that about 10 percent of them are enrolled in the public school system.

DREAM Act opponents say that the costs of enrolling upwards of a million students at public colleges and universities, particularly in the 12 states where these immigrants are concentrated, places an unsupportable financial burden on those institutions.

Steven Camorata, director of research for the Center of Immigration Studies said in his testimony that the federal government should provide funding to those states to offset those costs.

“If you hope this will be a gain for the taxpayers, that is in the long run,” Camorata said. “If you think that’s the case, provide the money to these schools.”

Twelve states already allow undocumented students to receive in-state tuition for public college and universities, and several others, including Iowa, have attempted to pass similar bills in the past year. Geofrey Fischer, project coordinator with the Iowa Immigration Education Coalition, said that Iowans were wary of the fiscal impact.

“Right now there’s a really negative feeling toward unfunded mandates,” Fischer said. “Iowans don’t like the idea of comprehensive immigration reform because of some of the negative components, but they support many tenets of it.”

Fischer said it was likely the legislation would be reintroduced this year as some costs are clarified, even though it initially had little support from state legislators.

In the Senate hearing, Duncan particularly emphasized the economic benefits of legalizing young, American-educated undocumented people rather than forcing them to work in—and contribute economically to—other countries.

“This is an investment, not an expense,” Duncan said, pointing out that one in four companies is started by immigrants, and that college education leads to higher incomes – and higher income taxes.

“The stakes are so high, not just for individuals and families, but for the country,” Duncan said. “It goes against our basic sense of fairness to shut the educational door to young people because of the choices of their parents.”