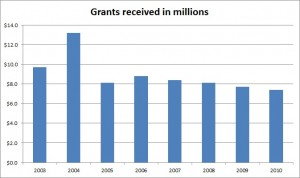

Kansas City received its first grant for emergency preparedness from the Department of Homeland Security in 2003. The city was cut from the program this year after receiving $71.4 million. Gina Harkins/MNS

W

ASHINGTON — Emergency preparedness tools ranging from equipment used to communicate with emergency officers to response training for police are at risk of being scaled back or eliminated because the Department of Homeland Security has scratched the city from its list of areas receiving special preparedness grants.

Kansas City, Mo. is one of 34 smaller cities that will lose the Department of Homeland Security funding from the Urban Area Security Initiative grant program later this year.

The cut will leave the Kansas City with a $7.4 million hole in its budget, and Gene Shepherd, who manages the Kanas City Office of Emergency Management, said the city hasn’t announced how it will make up the difference. Kansas City had been receiving the grant since 2003. Its first grant totaled $9.7 million. Subsequent grants averaged $9 million per year.

“The grants were being used for a lot of homeland security projects and emergency services,” Shepherd said. “A lot of it was used for training and tools that we used to communicate with other emergency offices.”

Smaller cities are reliant on these programs since they often need to pool regional resources to deal with a large-scale emergency.

Kansas City programs that are at risk due to the loss of funding include:

- Heavy rescue equipment

- A Fusion Center, which collects and shares information and intelligence between federal, state and local governments as well as information from the private sector

- Hazards material training

- Training programs for first responders and terrorism officers

- Tools and equipment used to communicate with other emergency offices

- Health Department programs addressing vaccines and biological threats

“We don’t have the personnel and equipment that larger cities have,” he said. “Attacks can happen in places all over. We are a major transportation hub and at the crossroads of the country. A lot of industry passes through here on our roads and trains. The threat definitely exists, it’s just not the high profile that New York and Los Angeles would have.”

Chris Ortman, Department of Homeland Security spokesman, said the department had to reassess the grant program after Congress cut a quarter of the grant budget.

“The highest risk cities in our country continue to face the most significant threats,” Ortman said. “And, consistent with recommendations from the 9/11 Commission, (this year’s) homeland security grants focus the limited resources that were appropriated to mitigating and responding to these evolving threats.”

The announcement to cut the number of cities receiving the grants from 65 to 31 was made in May, leaving more than 30 cities with losses of millions to homeland security programs. But concentrating the money in the areas most at-risk of a major terrorism threat makes sense to Paul Rosenzweig, former deputy assistant secretary for policy in the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, now Carnegie national security fellow at Northwestern University.

“Everybody’s at a possible threat,” Rosenzweig said. “But in a world in limited resources, you have to rank-order them.”

Rosenzweig said the process of ranking the cities in order of need and risk is a complicated process.

“It’s a massive formula,” Rosenzweig said. “It’s based on the assessment of risk which includes threat, vulnerability and consequence of an attack. It’s everything from what special things they have nearby, how many people live there and the relative degree for intelligence threat.”

But Shepherd said the loss of funding will hurt the city’s ability to respond to other types of events as well, like natural disasters.

“We sent a large portion of our fire and police departments to Joplin when the tornado hit,” Shepherd said. “A lot of regional assets were sent. But in the future, if that might happen we might not have the means to send help.”

Chief Richard “Smokey” Dyer of the Kansas City Fire Department agreed.

“We would not be honest if we did not tell the public that we will be less capable in the future than we are right now,” Dyer said. “We were operating at a C-level before we started receiving the grants. It won’t be like a boomerang that we’ll fall back to a C right away, but we’ll probably stay at a grade of A for a year or two and then go down to a grade of B, but I think within 10 years we’ll be operating back at a C-level.”

Rep. Emanuel Cleaver II, D-Mo., condemned the cuts to the grants in a statement made after the May announcement.

“This is a terrible time to withdraw support for our ability to train and equip police, firefighters, and other first responders and otherwise maintain the highest level of security,” he said. “If the safety of our communities is not a priority, I don’t know what is.”

But Rosenzweig said the money is applied top-down after all the cities apply, and the farther away you are from that model of what the formula calculates as at risk, the worse it is for the city.

“You have to fund your way down till you run out of money,” Rosenzweig said. “In terms of real risk, a state like Wyoming is largely overfunded.”