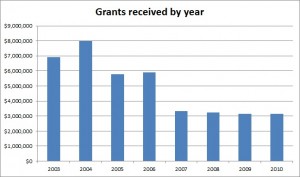

Sacramento received its first grant for emergency preparedness from the Department of Homeland Security in 2003. The city was cut from the program this year after receiving $39.4 million. Gina Harkins/MNS

W

ASHINGTON — Emergency preparedness tools ranging from mobile command posts to terrorism response training for police are at risk of being scaled back or eliminated because the Department of Homeland Security has scratched the city from its list of areas receiving special preparedness grants.

Sacramento, Calif. is one of 34 smaller cities that will lose the Department of Homeland Security funding from the Urban Area Security Initiative grant program later this year. The loss of $3.2 million – the 2010 federal grant — isn’t something the city is easily going to be able to make up, said Sgt. Norm Leong of the Sacramento Police Department. The city has been receiving grants from the Department of Homeland Security since 2003. Its first grant totaled $6.9 million. Subsequent grants averaged $5 million per year.

The effects of the funding loss on Sacramento’s emergency management and capabilities will be significant, according to Leong, the police department’s spokesman.

Without the programs funded by the grants, Leong said he feared that the city could easily become overwhelmed in an emergency situation.

“Our budget is terrible right now though,” he said. “I don’t think the city will be able to breach any gap that will be lost.”

Rep. Doris Matsui, D-Calif., tried to prevent the cuts to Sacramento. She condemned the announcement to cut Sacramento’s funding in a press statement released after the announcement.

“Sacramento is the capital of California, the most populous state in the Union, and the seventh largest economy in the world,” Matsui said. “It is critical to continue to support the anti- and counter-terrorism work being done there. It is unacceptable to leave this region without appropriate funding to ensure its protection as Sacramento, and the region as a whole, have important security needs.”

Smaller cities rely on these programs because they often need to pool resources to deal with a large-scale emergency in the region.

“Smaller cities have to grab regional assets whereas a city like New York City has 10,000 officers plus,” Leong said. “They might not need regional assistance in an incident.”

But Leong worried that the loss of funding, which was mostly used for training and operating systems already put in place, could weaken the city’s effectiveness in dealing with emergencies in the future.

“The cuts to these grants are more pronounced for us because of the additional budget situation we find ourselves in,” he said.

The list of Sacramento programs at risk of being cut include:

- Fusion Center: After 9/11, opened to better collect and share information and intelligence between federal, state and local governments as well as information from the private sector. One of many regional centers nationwide.

- Terrorism Liaison Officers: Officers specially trained to work with gathering information from the community, governmental agencies and the private sector and forwarding it to the appropriate intelligence organization.

- Emergency equipment: Heavy emergency equipment.

- Terrorism simulation exercises: Simulated emergency situations that allow the government to develop an emergency plan and identify groups responsible for certain activities.

- Mobile command posts: Mobile homes equipped with cameras and phones that can act as mobile command location in an emergency situation.

- Training first responders: Training programs to help first responders learn to deal with new threats and emergency situations.

The Sacramento Police Department currently trains Terrorism Liaison Officers; there are currently 450 in the region, Leong said. But that special training might not continue for new officers without funding.

“We have enough funding to keep it going for a year or two because we had savings from previous years,” Leong said. But beyond that, it might not be possible, he said.

The DHS announced in May it would drop the number of cities receiving the grants from 65 to 31.

Chris Ortman, Department of Homeland Security spokesman, said the agency had to reassess the grant program after Congress cut a quarter of the grant budget.

“The highest risk cities in our country continue to face the most significant threats,” Ortman said. “And, consistent with recommendations from the 9/11 Commission, (this year’s) homeland security grants focus the limited resources that were appropriated to mitigating and responding to these evolving threats.”

While 34 cities will lose millions in homeland security funds, concentrating the money in the areas most at-risk of a major terrorism threat makes sense to Paul Rosenzweig, former deputy assistant secretary for policy in the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, now Carnegie national security fellow at Northwestern University.

“Everybody’s at a possible threat,” Rosenzweig said. “But in a world in limited resources, you have to rank-order them.”

Rosenzweig said the process of ranking the cities in order of need and risk is a complicated process.

“It’s a massive formula,” Rosenzweig said. “It’s based on the assessment of risk which includes threat, vulnerability and consequence of an attack. It’s everything from what special things they have nearby, how many people live there and the relative degree for intelligence threat.”

Leong said Sacramento residents might not have been aware of all of the programs that will now be at risk.

“I think the community knows there are entities out there working on homeland security and safety and we try to explain the regional training going,” he said. “But I don’t know that they’re aware of what the loss of these grants will mean for the city.”