WASHINGTON — Despite their prevalent, tech-savvy online presence, terrorist groups may not yet have demonstrated the ability–or even interest in attaining the ability–to launch cyberattacks.

National security experts are not arguing against better security—they are just noting that while the U.S. faces many cyber threats, terrorism may not yet be one of them.

Terrorist groups’ use of the Web has proliferated in the past decade and according to former CIA Director Gen. Michael Hayden, they are “cybersmart.”

But Hayden said these organizations, perhaps surprisingly, have not exhibited any evidence that terrorists use cyberspace for anything beyond support activities. “I don’t know why. I really don’t,” he said during testimony before the House Intelligence Committee last week.

Cybersecurity expert James Lewis, of the Center for Strategic and International Studies, said causing physical damage and devastation using the Web is far more complicated than the minor attacks terrorist groups may be able to launch.

“They are looking for a splashier event,” Lewis said. “They want explosions and things that will play well on the nightly news. Making the traffic lights blink on and off might not do that for them.”

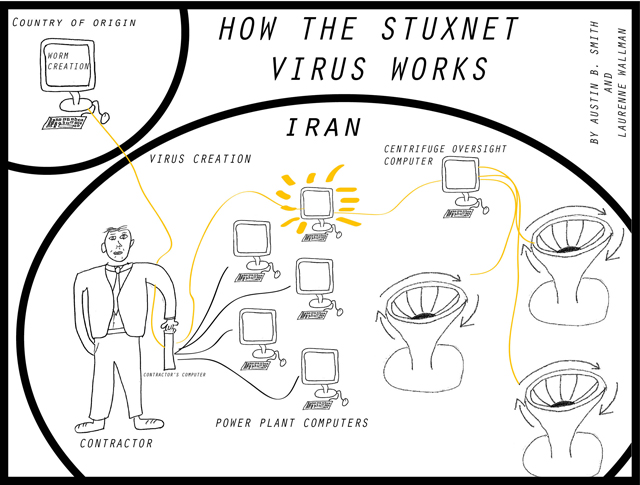

A key example of physical destruction caused by a cyberattack is the June 2010 Stuxnet virus, which infected computers at a nuclear reactor in Iran, causing it to malfunction and ultimately break. The undetected virus caused the closure of the plant and setbacks in Iran’s uranium enrichments program.

Experts said that U.S. infrastructure is no better protected than the reactor in Iran was, but that terrorist groups aren’t likely to have the resources to gain the internal knowledge they would need.

“It’s actually a lot harder not because of the technical component, but because of the amount of intelligence required to do it properly,” said Allan Friedman of the Center for Technology Innovation at the Brookings Institution, a nonpartisan Washington think tank.

Expert Liam O Marchu, of Symantec Corp., a California-based software security company, said, Stuxnet “has shown us that you can write a piece of software that will be able to change how a factory works.”

To replicate a similar attack — one focused on a particular target — would require precise insider intelligence and millions of dollars.

Terrorist organizations could look at Stuxnet as a blueprint, Marchu said, and they could also look at it to learn certain techniques. However, “the sophistication of the threats would depend on how skilled the attackers were and how much insider information they had.”

Lewis, whose research at CSIS focuses on Internet policy and cybersecurity, said the only organizations with the capability to do this—at the moment—are nation-states.

The U.S. Department of Defense argues that the cyberdomain breaks down the traditional concept that large-scale attacks require equally large-scale operations, which might give attackers a way to exploit U.S. vulnerabilities.

Since much of U.S. critical infrastructure–a likely target of cyber attacks–is operated by the private sector, the private sector needs to be involved in any security enhancements.

Lewis said he’s spoken with companies that see defending against terrorism as a responsibility of the government, not the private sector.

“That’s a perfectly reasonable line,” he said. “DoD needs to do something. The U.S. government needs to do something.”

The Obama administration is pushing Congress to strengthen private sector cybersecurity, which Lewis sees as a positive move. But he added that the Department of Defense should also be protecting these national security-related interests.

According to the DoD, they are.

The DoD “seeks to mitigate the risks posed to U.S. and allied cyberspace capabilities,” a DoD spokesman said, “while protecting and respecting the principles of privacy and civil liberties, free expression, and innovation that have made cyberspace an integral part of U.S. prosperity and security.”

While Hayden dismissed concerns of cyberterrorism attacks at the moment, he was quick to acknowledge the potential problems, calling U.S. infrastructure vulnerable.

“Eventually they’ll get this capability and then they’ll use it,” CSIS’s Lewis said.

After programmers created the virus, extensive information-gathering was required in order to infect computers that control the Bushehr nuclear reactor in Iran. The programmers found contractors who’s computers had a lower security level and who were likely to visit the plant, thus making them ideal carriers of the Stuxnet worm. Once those computers were infected, either via the Web or USB sticks, the virus quickly spread to computers within the Bushehr plant in search of the controlling unit. Once targeted, the centrifuge oversight computers were manipulated into showing that the reactor was operating correctly, when in fact the virus was causing the reactor to spin out of control.