WASHINGTON — As the “Occupy” movement spreads across the country, the chief criticism of the protesters seems to be: What do they want?

Everyone from President Barack Obama to labor unions seem to realize that the protests, which started on Sept. 17 in New York and have popped up around the nation, are born from frustrations many Americans are feeling about unemployment and economic inequalities.

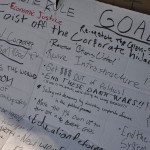

Yet the protesters still don’t have a list of demands. While individuals have their own grievances, at the macro level their unrest seems unfocused.

To understand the movement, though, you have to get on the ground level to see how “Occupy” organizes. It’s less about listing grievances, and more about establishing a process of incorporation — for now.

Forget about demands, at least until everyone involved feels their voice has been heard – the opposite feeling they’re getting from the “real” government.

“The point is for everybody to bring their ideas forward, and find where there’s common ground,” said Paul Taylor, a member of “Occupy DC” who has been participating in Washington since the group’s formation on Oct. 1. “Until we get a broad coalition of a bunch of individual ideas, we don’t know where the common ground is to work on.”

The protesters see it as using democracy to fix democracy.

“I believe this …”

If “Occupy” lacks a central voice, it’s by design, at least in Washington. The media committee asks participants to say, “I believe this” when speaking to the media, rather than “Occupy DC believes that.” The committee only functions to give out facts—when and where demonstrations will occur—not ideological statements.

It distances the movement from extreme views. It also intentionally keeps it from having a clear central voice.

Members can discuss even the smallest details at length. At a recent general assembly at McPherson square, Occupy DC headquarters, there was lengthy debate about whether there should be marshals during marches, followed by a second conversation over whether or not the marshals would wear bright orange vests. It lasted more than 30 minutes.

It’s Occupy policy that decisions can’t be made without the support of everyone in the group.

“The consensus process can sometimes look unwieldy and you know maybe it takes a little bit longer,” said Eddy Samara, a participant from North Carolina. “But the idea is that everybody’s voice counts and that people get heard.”

The group adheres strongly to one of its most-used cheers: “This is what democracy looks like.”

Clearly uneasy with establishing leadership, the movement looks for ways around it. Without an identified leader or point of view, the members believe the focus will stay on the collective and its eventual demands.

Leadership roles in the Occupy DC movement are constantly rotated, a tactic Julius Hobson, a politics professor at George Washington University who participated in the Civil Rights movement, says, “doesn’t allow for an attack on individuals as a means of discrediting the issue itself.”

“When you can formalize your process like this, it helps you to retain control,” Hobson said. “You have to keep your focus on what got you started. The moment you lose the focus on that, you lose your ability to try and convince people on your particular issue.”

But as is the nature of democracy, the more voices that come together, the harder it will be to come to consensus.

Avoiding protest pitfalls

Every general assembly, the “town square” of sorts, starts off with an introduction to the consensus process — the engine of the “Occupy” movement. Members aren’t counted as single votes; they show support collectively through “twinkling”—a noiseless, jazz-hand like applause.

If members have qualms with something being debated, they are allowed to make friendly amendments or proposals. If they still don’t like it, they can be a “stand-aside:” someone who doesn’t really believe in the item, but it won’t cause them to drop out of the movement.

If a person is completely against an idea, they are allowed to block a proposal—a rare gesture, according to “Occupy DC” members.

Through this process, “Occupy DC” has formed a number of committees and subcommittees, including teams to cover sanitation, legal, medical and media. The regular stuff of government.

The process can be long and arduous, but members insist it’s this careful process that will keep them around for the long haul.

This focus on control can be seen in the way “Occupy DC” interacts with other activist groups.

Hundreds of activists for varying causes gathered this weekend in Washington for the “Stop The Machine” rally in Freedom Plaza, steps from the White House. Though the two groups’ headquarters were just blocks away, “Occupy DC” made pains to both act in solidarity and also maintain its individuality.

“Occupy DC” tries to avoid the pitfalls of other protests — one member navigated a march around Freedom Plaza in downtown Washington, rather than through it, in fear that “the groups who have failed” will ruin the groundwork “Occupy DC” has laid.

That’s “tactical wisdom,” according to Joseph McCartin, a history professor at Georgetown University who is an expert on political and social movements.

“That’s part of what the jazz hands and the consensus model does is it breaks away from that other model which is more about existing organizations coming together in a coalition to try and move an agenda,” McCartin said. “What this movement is trying to be is a movement of people, not of organizations.”

What’s next for the “Occupy” movement?

There’s a chance “Occupy” could get too big, according to GWU professor Hobson.

If it does, protesters may have to find an even-more focused management structure. Especially since the movement isn’t slowing down.

Georgetown’s McCartin attributes its rate of growth to underlying dissatisfaction that many Americans are feeling about the nature of their country.

“People have felt that there are big wheels in motion rearranging the world and they don’t really have a say in much of any of that,” McCartin said. The “Occupy” movement, he says, is a way for people to finally feel like they’re finally being listened to.

But why protesting? What motivates a person to take action on the streets or camp out in a park?

“Being part of a protest is a very powerful thing,” said Jennifer Hadden, a University of Maryland professor who studies social movements and who just returned from “Occupy Wall Street” in New York.

“I think its about solidarity for people who are trying to be politically engaged. At a personal level it is very fulfilling and emotionally intense.”

Will they be here through winter?

The question remains: Is this approach to protesting sustainable? Can “Occupy” focus on procedure now and demands later and be successful?

“Occupy DC” has already experienced that control can’t always be absolute. Many activists at the Freedom Plaza event identified themselves with the Occupy movement — they held up cardboard signs with the hashtag #occupyDC on them. They shouted similar cheers.

And not everybody wants to wait for consensus — one general assembly started with 120 people, but filtered down to 70 or so as the meeting hit the 90-minute mark. It’s tedious.

“If you look at a movement like this, it’s quite diverse,” Hadden said. “Getting them beyond the point where you agree on what you don’t like can be quite the challenge.”

What’s the forecast, then, for a group still finding its voice?

“Their success will depend on whether or not they can sustain it, and whether or not they understand they are in a marathon and not a sprint, ” Hobson said. “When the weather changes, will they still be there?”

A few weeks into the “Occupy” movement, the critics are right: It doesn’t know what it wants.

But that’s exactly where it wants to be.