Three undocumented workers share this room at a labor camp in Wilson, N.C. (Gabriel Silverman/Medill News Service)

WILSON, N.C. – For every bucket of sweet potatoes Pablo picks he gets 40 cents. At that rate he’ll need to pick and haul 3,750 buckets to eclipse the $1,500 he paid to a coyote – a term for someone who helps undocumented immigrants jump the U.S. border.

In truth, that number of buckets is higher because Pablo’s boss deducts money for housing, cleaning costs and taxes.

Many undocumented agriculture workers do pay taxes. It’s commonplace for them to present farmers with fabricated Social Security numbers and doctored I-9 tax forms. It gives the farmer a paper trail to point to if U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement comes knocking.

About 100 miles southwest in Carthage, N.C., Cruz Diaz Montalvo is working in the U.S. legally with an H-2A visa, the only temporary guest worker program for agriculture. Being here with that visa means he is guaranteed a tax-free $9.30-an-hour wage, free housing and free transportation to and from Mexico.

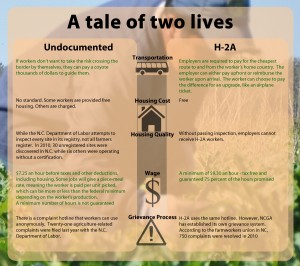

Despite performing the same arduous work that keeps American agriculture afloat, they represent a tale of two labor groups: The select few with an H-2A visa are entitled to an elevated life while swaths of undocumented workers take a gamble, hoping for the best.

Montalvo is lucky because an H-2A visa is only issued to a foreigner when a farmer can’t find willing U.S. workers. But farmers rarely use the program because many find it overly bureaucratic and costly.

Even in North Carolina, where farmers have banded together to help better navigate the program through the North Carolina Growers Association, the majority of farm hands remain undocumented. Estimates put the total number of unauthorized workers at 70,000 to 100,000 compared with 9,000 H-2A workers.

Life as a migrant farm worker is not easy. But if a foreign laborer is fortunate to come through the H-2A program, he is guaranteed an elevated standard of living. Here are a few differences between between H-2A and undocumented workers. (Gabriel Silverman/Medill News Service)

Relationships matter

Given the opportunity, Pablo, who asked not to be fully identified because he is here illegally, says he would have come to the U.S. through the H-2A program. But he, like all the undocumented workers interviewed for this article, didn’t know about the program until arriving in the U.S.

It’s because information about the program is primarily disseminated by word of mouth among family and friends. If a farmer decides to hire more H-2A workers, he’ll likely ask his current employees to find them.

Montalvo heard about the program through his father-in-law.

“The number of workers able to come with an H-2A visa depends on how many growers are using the program and how many workers they request each year,” said Briana Connors, a union leader with the Farm Labor Organizing Committee. “There just aren’t enough growers using the program.”

Farmers need the help and will hire workers whether or not it’s through the program. So in the absence of an H-2A visa, the only option is to enter the country illegally, Connors said.

This is not the Biltmore

The toilets at Pablo’s camp are inches apart. There are no dividing walls. The showers also lack partitions.

“I’m sorry to say that is absolutely up to code,” said Regina Cullen, head of the North Carolina Department of Labor’s Agricultural Safety and Health Bureau.

H-2A or not, seasonal farm workers who pick America’s vegetables, cut its tobacco and harvest its Christmas trees live a meager lifestyle. The work is physically demanding and housing is often basic.

Montalvo’s barracks had concrete floors and cinder block walls, an improvement compared with Pablo’s waferboard structure.

“Could it be better? Of course it could be better,” said Lee Wicker, deputy director of the N.C. Growers Association, which accounts for more than 7,000 H-2A workers. “But you can’t produce crops cheaply and efficiently and provide Biltmore-style housing for farm workers,” he said, referring to the historic 250-room Asheville, N.C., estate built in 1895 by George Vanderbilt. “So you have to have realistic measurements.”

While some undocumented laborers experience better conditions than their H-2A counterparts, in general H-2A carries a higher standard, said Connors.

“One of the biggest differences between H-2A and non H-2A is 100 percent of H-2A housing is inspected,” Wicker said. “If it’s not H-2A, there’s a high probability that it’s not inspected.”

Without certified housing, H-2A employers can’t get workers. And while non-H2A housing is legally required to be inspected to the same standards, the North Carolina Department of Labor discovers dozens of unregistered sites each year.

In 2010, 1,314 sites were certified to house farm workers by the NCDOL. Another 30 had failed to register and six were registered but were operating without certification.

A potential solution emerges

While Pablo arrived in North Carolina by traveling state-by-state, Montalvo came on a bus from the border chartered by the NCGA. Upon arrival Montalvo was briefed on safety regulations and given an overview of his work contract. Worker protection groups were there to meet him.

Farmer and worker advocates alike have criticized the H-2A process. Farmers believe the program is too burdensome. Worker advocates say the program doesn’t do enough to protect a vulnerable population.

But while Washington tries to find a policy solution, the NCGA and FLOC may have found a workable fix.

By pooling the resources of its several hundred members, the NCGA is able to provide a more streamlined process

“These workers have more exposure to government agencies and support agencies than any other farm workers in the state,” Wicker said.

In 2004, after many lawsuits against the group, the NCGA signed a labor contract with the Farm Labor Organizing Committee on behalf of H-2A workers

“It’s important to make the distinction, too, between H-2A under union contract and H-2A not under union contract,” said Justin Flores, union leader with the Farm Labor Organizing Committee

The agreement provides more guarantees for the workers, including sick pay and the ability to come back with a new employer. But, most important, it establishes a formal grievance process independent of the Department of Labor.

If something is wrong – ranging from a discrepancy in pay to a broken window – workers can initiate a process through the union agreement that will help resolve the problem.

Pablo and his undocumented cohort have very little recourse if their work or living conditions are substandard. There is an anonymous hotline through the NCDOL to report problems, but few use it because of their legal status, Connors said.

In a few weeks Pablo will follow work down to Florida, but said he hopes to one day come back with an H-2A visa.

Montalvo is planning on returning next year, which will be his 23rd. He says he has returned every year because it has helped pay for his children’s education: one has become a teacher, another a lawyer and two more are in college.

- In this H-2A housing structure in Carthage, N.C., three to five workers share a room – typical for migrant housing. (Gabriel Silverman/Medill News Service)

- Three undocumented workers share this room at a labor camp in Wilson, N.C. (Gabriel Silverman/Medill News Service)

- An undocumented worker in Wilson, N.C. shows off the stained and worn-out mattress that was provided to him. (Gabriel Silverman/Medill News Service)

- The men’s bathroom in one undocumented labor camp in Wilson, N.C. right after it was cleaned by workers. The lack of partitions between toilets or showers does not violate migrant housing code. (Gabriel Silverman/Medill News Service)

- Briana Conors of the Farm Labor Organizing Committee talks with a 23-year-old undocumented worker in Wilson, N.C. (Gabriel Silverman/Medill News Service)

- Two women, living in the U.S. without a visa, prepare food in the camp’s kitchen in Wilson, N.C. (Gabriel Silverman/Medill News Service)

- Cruz Diaz Montalvo, second from the left, poses with three of his H-2A coworkers in Carthage, N.C. Montalvo says he has been coming through the program for 22 years. (Gabriel Silverman/Medill News Service)

- A farm worker visa picks zucchini in Engelhard, N.C. (Gabriel Silverman/Medill News Service)

- By pooling resources, North Carolina Growers Association members are able to streamline the H-2A process. Here in Vass, N.C., new workers are given an overview of safety regulations prior to getting on buses that will transport them to Christmas tree farms. (Gabriel Silverman/Medill News Service)

- An H-2A worker looks over material during an introduction at the North Carolina Growers Association headquarters in Vass, N.C. (Gabriel Silverman/Medill News Service)

- An H-2A worker with the North Carolina Growers Association holds a labor contract in his hand as he is briefed on safety regulations in Vass, N.C. (Gabriel Silverman/Medill News Service)

- Life as a migrant farm worker is not easy. But if a foreign laborer is fortunate to come through the H-2A program, he is guaranteed an elevated standard of living. Here are a few differences between between H-2A and undocumented workers. (Gabriel Silverman/Medill News Service)