The special torture of dealing with the military comes from how more and more of us have no connection with the military. But that’s something for cultural critics and policy scholars to contend with. As far as getting one’s head around practical matters like the rank structure, that’s something anyone can do. Read on for a crash course in the chain of command (some things have been bolded for convenience).

Style issues: Let’s start with some basics. First, let’s go to the AP Stylebook, for when this stuff comes up in writing:

- Capitalize rank only when used as a formal title before the full name of someone in the military.

- Use the abbreviation for their rank. Spell out the entire rank title when substituting it for a name. Leave it lowercase.

- On subsequent references, use only the last name.

Some ranks aren’t mentioned in the style guide. You’ll have to confer with your editors on how to proceed in that case.

The Navy has ratings like “machinist,” “radarman,” etc., and the other branches have things that are similar. These are job descriptions, essentially. People in the armed services might tell you them, and if you are writing for Military Times, you want to know it. If not, ignore it and don’t let it confuse you. I try to approach any title from the standpoint that they only matter as much as the story needs them to, and that’s usually not much. With defense stories, rank, being the minimum, will often work fine. Also, each service has their own abbreviations for ranks, and they are not the same as AP’s.

Who’s who: But before you can guess at a service member’s rank, you need an idea of their branch. Check the uniform to know that:

- Army:

- Black coat and blue pants with yellow stripe; white top with blue pants and yellow stripe; white top/black coat with black skirt; dark green coat and pants

- Navy:

- The sailor’s cap should be a dead giveaway; all white; all khaki; khaki shirt and black pants

- Air Force:

- All dark blue; light blue top and dark blue pants/skirt; occasional flight suits

- Marines (they have a lot):

- Lots of red accents on blue. Khaki top and blue pants with red stripe; khaki top with blue skirt; all dark green; khaki tops and dark green bottoms; blue coat and white pants

Bear in mind there are a lot of different uniforms out there, and they military likes to change them around. If they’re in fatigues, I can’t help you. Sorry.

Who’s what: As for how to tell who is what rank, let’s start with knowing where to look. Depending on the branch of the military and which uniform they’re wearing that day, you can follow this heat map to get a better idea of where to look for the tell-tale rank insignia.

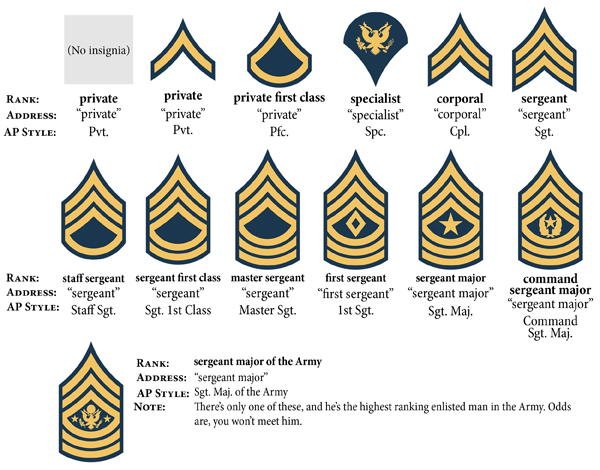

Now, for what to look for. Let’s start with the enlisted ranks. Here they are for the Army – going left to right and top to bottom – from lowest rank to highest.

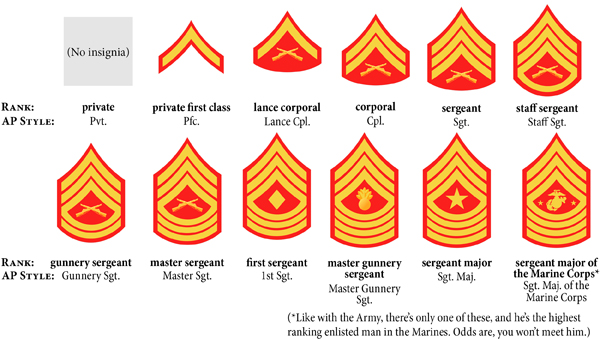

For verbal addresses, they seem to like the whole rank. Go ahead and ask. Also, I’m willing to bet it’s cool to call the sergeant major of the Marine Corps “sergeant major.”

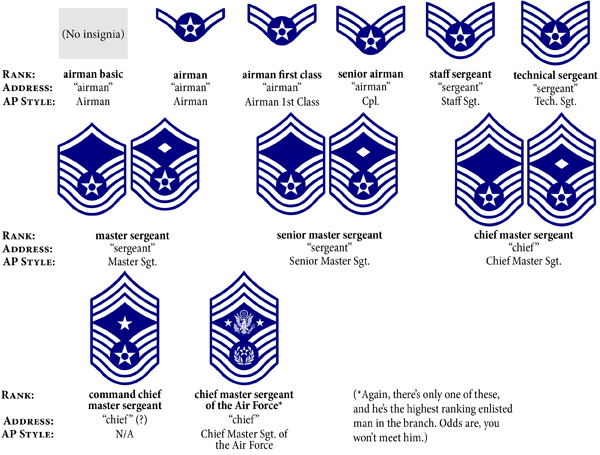

The Air Force:

See those little diamonds on some of the sergeant-level ranks? That doesn’t actually denote another rank, but a separate duty with that rank. And “chief” for command chief master sergeants is my best guess. Never met one.

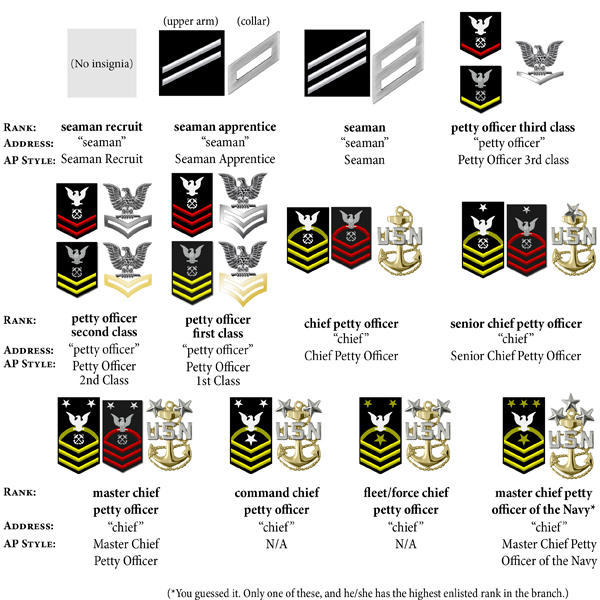

As for the Navy, they call them “rates,” not ranks, but they’re the same thing. Here are the sleeve and collar insignias:

For the seaman-level ranks, they might be different colors depending on their job. The number of stripes is the thing to look for. And when talking to petty officers, “petty officer” is a good place to start. “Chief” is common for the higher-ranking petty officers. “Mister/Ms.” is technically correct as well.

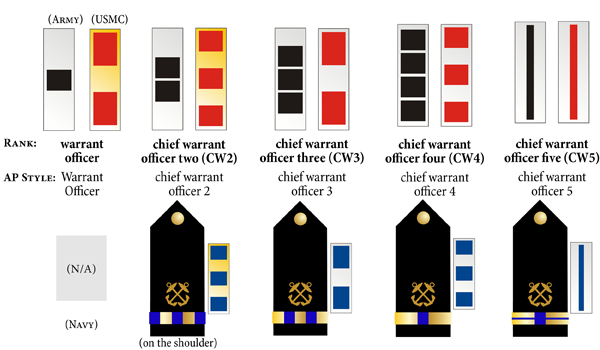

Confused? That’s normal. Recruits spend weeks getting reminded, usually via yelling, about how this is not really intuitive. Don’t feel bad. In between enlisted ranks and officer ranks are the warrant officers. These men and women tend to have highly specialized, specific jobs. Usually, you’ll find the pins on the collars or the shoulders.

The Army, Marine Corps and Navy have the same ratings for warrant officers. The Air Force doesn’t have them. Again from lowest to highest:

As for address, “Mister” or “Miss/Ms./Mrs.” is customary, at least according to Army documents. “Chief” is also common.

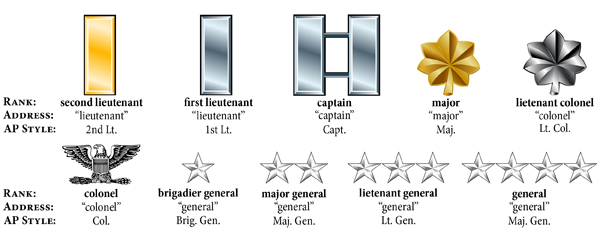

The officers, the upper managers who run things, are a little more simple. In case you didn’t know, officers outrank enlisted men and warrant officers. Even the highest ranking enlisted member of the Army calls a second lieutenant right out of ROTC “sir.” Non-commissioned officers are high-ranking enlisted men, not officers; the term sometimes creates confusion. I’ve heard them described as the middle managers of the military.

Here is the rank order and insignia for the Army, Marines and Air Force:

One strategy I found for sorting it out was to think of the symbols metaphorically, then measure their degree of proximity to God: Gold, for second lieutenants, is the densest metal, thus deeper in the ground. Then silver, which is less dense. The oak leaves of the major and lieutenant colonel ranks are above the ground, and the colonel’s bird flies above. Finally, there are the stars in the sky.

Another, less strange system meant specifically for the generals was the mnemonic BMLG or “be my little girl/general”: brigadier general, major general, lieutenant general, general.

There is a five-star rank, but it’s only for special occasions, like world wars.

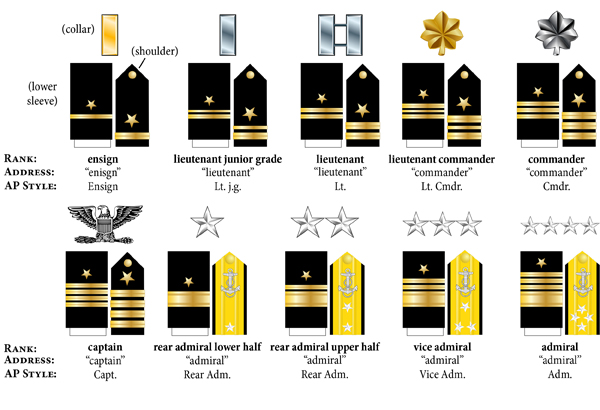

The Navy mix it up a little. These insignias are for their officers, and might be found on their sleeve, shoulder or collar:

I doubt it will come up, but “captain” can also refer to the commander of a ship, regardless of rank. So can “skipper.” Likewise, the “commander” can refer to the executive officer of a ship (the second in command) regardless of rank. “XO” or executive officer also refers to that position.

I doubt it will come up, but “captain” can also refer to the commander of a ship, regardless of rank. So can “skipper.” Likewise, the “commander” can refer to the executive officer of a ship (the second in command) regardless of rank. “XO” or executive officer also refers to that position.

Also, I’ve never seen anyone called “rear admiral lower half.” It’s always been “rear admiral.” You might say “one-star” or “two star” admiral, but that’ll be up to you and your editor.

One last hint on Navy officer ranks: they’re the same as the ranks in “Star Trek.” For some people, that will be helpful.

A note on rank in verbal/otherwise addresses: Please note these are just recommendations, and none are cut-and-dry. Some reporters are on a first-name basis with high-powered generals. A Marine Corps captain told me, as a civilian, I could call him “asshole” and it wouldn’t really matter. Of course, you don’t want to do that. Ever.

Conventions and etiquette for this will vary between branches and between people. A good place to start would be rank, like, “Hello, lance corporal Matarrese.” For officers, “sir” and “ma’am” would probably never hurt. Not sure? Just ask.

There’s a lot of nuance and detail to this stuff I left out for clarity (and my own sanity). Again, the most important thing to remember is, if you don’t get it, just ask. It’s better to ask politely beforehand than screw up later and look like an ass.

Reporter Andy Matarrese, who covers national security, will graduate from the Medill School of Journalism in June. He wrote this piece for Washington Reporting 2.0., an occasional column about covering D.C.