WASHINGTON – Cable news coverage of the three recent tragedies – the Boston Marathon bombing, a fertilizer factory explosion in West, Texas, and a factory collapse in Bangladesh – offer insight into public perceptions of risk and the ways networks respond to those perceptions.

At the same time, experts say the networks themselves can heighten irrational fears through excessive or decontextualized reporting. That reality raises issues for journalists, who must balance such considerations against the visceral impact and inherent newsworthiness of an event like a terrorist attack.

A review of transcripts from CNN, MSNBC, and Fox News gathered by monitoring service TVEyes found that the overwhelming majority of the networks’ coverage went to the Boston attack, even in the weeks following the other two disasters.

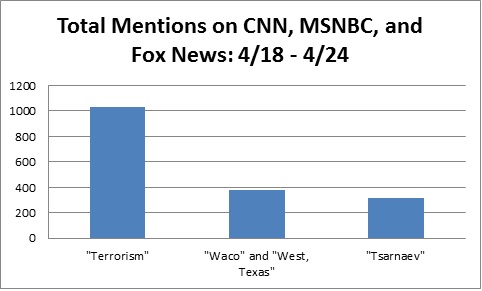

In the week after the April 18 Texas fertilizer factory explosion that killed 15 people, guests and hosts on the networks said the words “West, Texas” – the exact location of the explosion – or “Waco” – a better known town close by that was routinely referenced instead of West – a collective total of 381 times.

That compared to the terms “Tsarnaev” and “terrorism” which were used more than four times as often, (a combined 1,347 times). Tamerlan and Dzhokar Tsarnaev are accused of conducting the April 15 Marathon bombing.

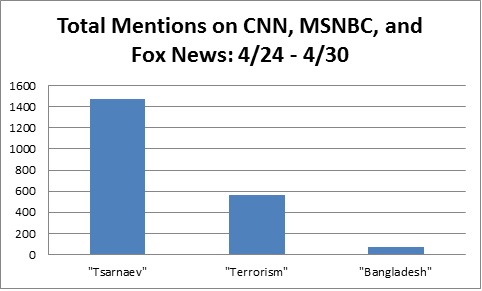

That trend continued the next week, in the direct aftermath of the Bangladesh factory collapse tragedy that killed at least 650 people. In fact, usage of the terms “Tsarnaev” and “terrorist” increased to a collective total of more than 2,000 mentions. In contrast, “Bangladesh” appeared in transcripts just 70 times.

A review of available transcripts shows that during both periods, “terrorist” was used primarily in relation to the Boston bombing.

CNN, MSNBC, and Fox News did not respond to a request for comment on the findings.

Mark Jurkowitz, Associate Director for the Pew Research Center’s Project for Excellence in Journalism, said multiple factors are responsible for this outcome. Some were simply logistical. The Boston Marathon was already receiving major coverage, including live coverage. Boston is also a major urban area, which made it easier for television networks to get footage in the days after the bombing. A relatively small number of cameras captured the events in West, Texas and Bangladesh, and both locations were comparatively difficult for U.S. media to access.

But the biggest factor impacting coverage was a psychological one. Jurkowitz said interest in the bombing was driven by the primacy of personal safety in the minds of both the American public and many reporters alike – concern that domestic terrorism triggers in a unique way.

“If the, ‘Am I safe?’ question drives news consumption and news attention, then you see the huge difference between Waco and Boston,” Jurkowitz said.

Jurkowitz said the Texas explosion lacked “the specter of the unknown, the specter of an attacker who could prey on anybody at any time.”

“While many Americans might have watched the marathon and said, if this can happen there it could happen anywhere, unless you’re working at a fertilizer plant somewhere, the overwhelming majority of Americans are going to look at Waco and not ask the question, am I safe?”

Similarly, the collapse in Bangladesh did not represent a threat to Americans, and was relatively unsurprising to U.S. viewers, considering their conception of Bangladesh as an endemically poor country where disasters are common.

Such psychological factors prove more significant in the public imagination than either the number of individuals killed in a particular event or the fact that, from a statistical standpoint, terrorism represents a minimal threat to the average American.

“Risk is a matter of what scares us, and what matters to that is the nature of how people die, not just how many,” said David Ropeik, a former television reporter who now studies the way in which the media covers public safety issues.

“West, Texas was an accident,” Ropeik said. “Boston was murder. And psychologically, we’re more scared of risks when we know people are out to do us harm. The purposefulness of the act changes how it feels.”

In the same way that most Americans didn’t relate an accidental fertilizer plant explosion to their own circumstances, Ropeik said the literal and perceived foreignness of those killed in Bangladesh made their suffering seem equally foreign and therefore of less interest.

Ropeik said these realities present a challenge to journalists, who must find a way to cover stories about public safety in a way that puts them in proper context. He said that too often, media reports unnecessarily heighten public anxiety in a way that creates a “positive feedback loop to our fear.”

That definitely applies to coverage of terrorism, he said, advocating for reporting that puts such stories in a proper statistical context.

“If a dirty bomb goes off in America, it will cause far more stress and economic loss because of excessive fear than it will be physically dangerous,” he said. “That harm can be laid squarely at the feet of the media, which is where that fear comes from.”

Ropeik said the Hippocratic oath applies to journalists as well: Do no harm.

“By hyping the alarmist coverage of the dramatic stories that emotionally resonate, they magnify our fear,” he said. “And that does harm.”