WASHINGTON — President Barack Obama made expanding the pool of insured Americans and guaranteeing coverage for those with pre-existing conditions cornerstones of his health care reform effort.

The resulting Affordable Care Act might well have been written for Illinois resident Ann Battenfield. She lacked insurance for 18 months before health care reform became a reality.

Battenfield has been self-employed since the 1990s and, as a result, was self-insured, but toward the end of that decade it became increasingly difficult to get coverage.

“By about 2001 I was out of options,” Battenfield said. “For a while I would take consulting jobs with companies who offered to keep you on their insurance as long as you worked with them, even though I didn’t want to work for the company.”

The work was temporary. So, after she finished the job, she would be eligible for COBRA, government-sponsored health insurance for people who lose their jobs or see a reduction in hours.

In the early 2000s, Battenfield stumbled upon a union that offered health insurance, a windfall that lasted until late 2008.

Percent of uninsured residents by state

(Numbers obtained from Kaiser State Health Facts)

But she has periodic limb movement disorder that occurs during sleep. Insurance carriers consider it a pre-existing condition, meaning obtaining coverage didn’t come down to just costs. It was also eligibility.

“I have to take a drug that is on the do-not-insure list,” Battenfield said. “Even though I’m healthy in all other ways and the drug isn’t even expensive, it’s just on the we’re-not-going-to-insure-you list.”

Before the Affordable Care Act became law, Illinois had a program that allowed people with pre-existing conditions to get coverage, but costs were prohibitive, Battenfield said — $1,800 each for her and her husband, Steve Veach.

In this case, Battenfield benefits from a second focus of the law — eliminating preclusion by pre-existing condition. Battenfield says the premiums for her and her husband are still pretty expensive: about $1,000 a month, but at least affordable.

The costs were brought down by a part of the law that required states to set up a program where people with pre-existing conditions could get insurance at rates that people without pre-existing conditions pay.

“When the health care act passed and Illinois instituted its insurance for (people) with pre-existing conditions,” Battenfield said, “that was the first time we were insured in at least 18 months, it may have been a little bit longer.”

The economic impact

Many of the provisions of health care reform kick in starting Jan. 1 of next year, including available tax credits to help the uninsured get coverage through state-based exchanges. This is a third focus for supporters: lowering the cost for consumers.

“Individual tax credits are going to be an extraordinary large variable in this law,” said Bob Graboyes, a senior fellow at the National Federation of Independent Business, which played an integral role in the legal battle against the law and its possible economic impact. “If it were to work as planned, it would be very large. How large, again, is subject to enormous variability,” he said.

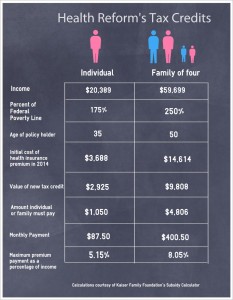

Above are two examples of how the tax credits might work. The first example is a 35-year-old woman. The second example is a husband and wife, both 50, and two children. (Numbers calculated using Kaiser Family Foundation Subsidy Calculator.)

The new tax credit may indeed impact Battenfield. Based on calculations, she could see a 45 percent to 60 percent reduction in her premiums, potentially saving her a good bit of money.

Battenfield said the $1,000-a-month premiums were taking a significant toll on how much she and her husband could invest in the business they own together.

Aimed at not only providing coverage but also limiting how much a family contributes to its premium, the tax credits could slow down the skyrocketing amount of money families spend each year on health care.

According to a RAND Corportation report, families saw their incomes grow from 1999 to 2009. But health care costs took a big bite out of the increase. This left them with, on average, only $95 more a month in 2009 than in 1999. Had health care costs risen alongside Consumer Price Index, families would have had $450 more a month. The surging costs of care took up $355, close to 80 percent of the family’s wage increase.

The steep increases actually drove health insurance costs up so much that two weeks before the supposed renewal of Battenfield’s union-provided health plan, the union sent out a note to its members informing them insurance was too expensive to maintain.

“We had two weeks of insurance left, and that was it,” Battenfield said.

With the combination of the regulated exchanges and health insurance tax credits, consumers could end up with a little bit of extra money in their pocket, said Elise Gould, a health care economist at the labor union-backed Economic Policy Institute.

Battenfield may use the money she saves in several ways.

“(The left over money) is (going to) one of three things,” Battenfield said, “it’s paying off existing debt, it’s money not going into debt, or it’s money being put back into the business to recapitalize so that we can help build it.”

Eligibility for the new tax credits is determined by household income as a percentage of the federal government’s poverty line, which is “chained” to the Consumer Priced Index. Assistance for premiums will begin at 100 percent of the poverty line and stop at 400 percent, according to proposed rules from the Internal Revenue Service. If a state chooses to expand its Medicaid program though, people between 100 percent and 138 percent of the poverty line may be eligible for that.

Percentage of uninsured eligible for tax credits by state

(Note: Issues ruled by the Internal Revenue Service dictate that anyone between 100 percent and 400 percent of the federal poverty line are eligible. It could be slightly different though if a state decides to participate in the Medicaid expansion.Numbers obtained from Kaiser State Health Facts.)

Another part of the law states those receiving the tax credits can spend no more than 9.5 percent of their yearly income on health insurance premiums, with the burden get higher as a family’s income increases.

Challenges abound

Battenfield’s story represents a best-case scenario though. The size and scope of the law presents plenty of challenges.

Only 17 states decided to run their own exchanges, leaving the federal government to partially or completely implement the insurance exchanges in 33 different states.

“First of all, the big question, and for me it is a very big question,” Graboyes said, “is whether in fact the mechanisms necessarily to deliver that will be open in 2014.”

The states and federal government face an Oct. 1 deadline, which is when exchanges must be ready to accept applicants. That means in just under four months the insurance marketplaces must be operational.

While the state-based marketplaces are also designed to keep health insurance costs down, it remains to be seen if it will even work.

Some argue that the ability for consumers to shop around keep costs down; people will buy the best-value plan, causing companies to charge reasonable prices for premiums. Gould questions whether this will really happen though.

“There’s already incredible concentration insurance company power in this country,” she said. “A small number of insurance companies yield a high level of market power. So to think that the competitive market is going to bring down prices, it’s more questionable in that kind of situation.”

This is may be unlikely to happen anytime soon, as Gould said there were “pretty significant barriers” in entering the insurance market, including garnering an extensive list of providers that will entice people to a new insurance company.

Some harbor concerns whether employer-sponsored insurance will still be commonplace. Graboyes fears many businesses will stop offering these benefits to their employees, sending the workers to the exchanges to buy insurance, many with the help of the tax credits.

“If, in fact, a lot of employers do that, as I expect they will,” he said, “then the amount of those subsidies is going to get quite large and it will have a negative impact on the federal deficit.”

For Ann Battenfield, the new health care law presents real hope. Jan. 1 will show how it fully plays out.