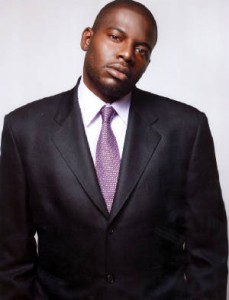

WASHINGTON — Gun buybacks are usually in the domain of local government, but music industry executive Michael “Blue” Williams and a few intrepid community leaders in New York are using turn-in-your-guns programs to save the lives of at-risk youth.

WASHINGTON — Gun buybacks are usually in the domain of local government, but music industry executive Michael “Blue” Williams and a few intrepid community leaders in New York are using turn-in-your-guns programs to save the lives of at-risk youth.

“In New York City, violence and crime committed with guns are committed by minorities between 16 and 34 years old and 80 percent of that crime is committed by that target audience,” Williams said in a phone interview. He said this age group largely makes up the hip-hop music audience, which he has worked closely with for almost 20 years.

With a famous client list full of Grammy award-winning artists like Outcast and CeeLo Green, Williams has the hip-hop bona fides. Crime data from the 2012 Crime and Enforcement Activity in New York City Report showed that minorities were arrested for 96 percent of all crimes involving a firearm.

Numbers aside, Williams’ connections in the hip-hop community gives him an advantage in the push to get guns out of the hands of young people. That is why Williams, president of Family Tree Entertainment, created the Guns 4 Greatness program, the first privately funded gun buyback program in New York City.

“The point of this to me is that hip-hop needs to get in front of the news cycle, so to speak. All you hear about the hip hop artist is once we get in trouble,” Williams said.

The organization is attempting to attract a demographic that many buyback drives have had a hard time reaching. Due to the anonymity of gun buybacks, studies are rare. According to the 1994 University of Rochester study, “Money for guns: evaluation of the Seattle Gun Buy-Back Program,” the average age of a participant was 51 years old. The Rochester study showed no strong correlation between buyback programs and violence reduction.

Typically the guns returned in the buybacks come from older residents and aren’t criminally connected.

Williams said his links to the community and his unique ability to identify with young people allow him to better relate to younger people looking to change their lifestyle choices.

The exchanges, usually managed by municipal governments, continue to grow in popularity across the country. New York City has an ongoing buyback program and citizens can turn in weapons at any time in exchange for money.

“These partnerships are intended to encourage broader community support for getting illegal guns off the streets,” Mayors Against Illegal Gun said in a statement. The coalition is made up of about 850 mayors from 44 states across the U.S. working to stop the flow of illegal guns into their cities.

Studies on gun buyback programs in other regions of the country are not definitive in their results. University of Wisconsin-Parkside Professor Matthew D. Makarios said that gun buybacks “at best, hope to affect gun crime indirectly by decreasing the availability of guns … Little evidence has been shown to support the assumption that they are able to decrease the number of guns available to criminals, much less gun crime.” (Makarios made the statement in his 2008 article, “The Effectiveness of Policies and Programs That Attempt to Reduce Firearm Violence: A Meta-Analysis.”)

For many researchers, the efficacy of gun buybacks is unclear. Makarios argues that comprehensive probation strategies are a more effective approach to reducing crime.

In his Guns 4 Greatness program, Williams hopes to prevent crime and also reduce recidivism rates.

“Watching young men come to court not prepared and being railroaded. Taking deals that would give them felonies that would follow them for the rest of their lives. Then I heard Commissioner [Raymond] Kelly challenge the community to come up with a better solution than ‘Stop-and-Frisk,’” Williams said.

Stop-and-frisk is a police practice that has recently come under fire by several civil liberties advocacy groups in New York City.

“We don’t call for a stop to the practice overall,” said Candis Tolliver, a senior organizer with the New York Civil Liberties Union. “Because we understand when it’s used lawfully it’s an effective crime-fighting tool, but we see that that is not what is happening in stop-and-frisk over the last 10 years and under this administration. And we feel there needs to be reforms to the practice because of it.”

Stop-and-frisk practices gained legitimacy after a 1968 Terry v. Ohio U.S. Supreme Court ruling that allowed police offers who suspect a person has committed, is committing, or is about to commit a crime to stop and question that individual. If the officer believes he is in danger, the person is frisked and searched for weapons. In 2012, New York city police stopped 532,911 individuals and of those, 89 percent had no charges filed and 87 percent were black or Latino.

Guns 4 Greatness is Williams’ attempt to meet the police commissioner’s challenge to propose an alternative to stop and frisk.

Williams’ group is not only working to get firearms off the streets, but also offers mentors to young people who turn in guns, along with financial compensation.

“What I appreciated most was the mentoring piece,” said Rev. A.R. Bernard, pastor at Christian Cultural Center. That’s “more than buying guns back, but also developing a relationship with these individuals to introduce them to someone in any industry that they are interested in.”

Bernard’s Brooklyn church hosted Guns 4 Greatness’ inaugural event on March 29. During the drive, 115 firearms were collected, ranging from revolvers to rifles, including one assault weapon.

Williams continues to tap into his network of friends and famous clients in order to provide mentors and also expand the program nationally. According to the website, its purpose is “to help end the senseless gun violence that has taken and destroyed so many lives in urban communities.”

A 2007 study by the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies in Geneva found that there are 270 million firearms in the United States. Some estimates have the number higher, but recent Gallup polling indicates that gun ownership is on the decline.

“No one knows what one gun will do,” Williams said.