WASHINGTON –The National Instant Criminal Background Check System, started in 1998 as a way to keep guns out of dangerous hands, has become a lightning rod for critics in the ongoing debate over expanded background checks for prospective gun buyers.

The history

The FBI created the background-check system in collaboration with the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms (ATF), and state and local law-enforcement agencies. It was mandated by the Brady Handgun Violence Protection Act of 1993.

The law looked to implement “a waiting period” before handgun purchases were completed and demanded “the establishment of a national instant criminal background check system to be contacted by firearms dealers before the transfer of any firearm.” It was introduced by then-Rep. (and now Senator) Charles Schumer, D-N.Y., in February 1993 and signed into law by President Bill Clinton on Nov. 30, 1993.

The background-check system, called NICS, went online on Nov. 30, 1998.

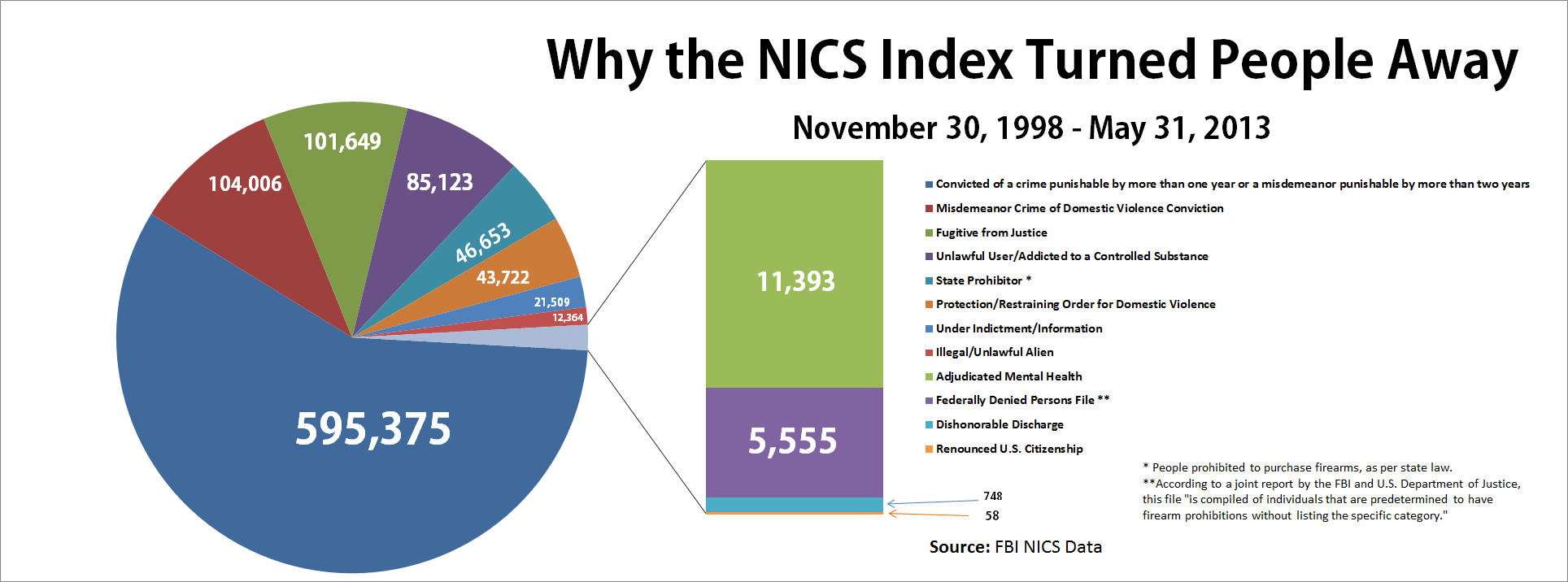

As of May 31 of this year, more than 170 million NICS firearm background checks had been performed in transactions in all 50 states (plus the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico and other U.S. territories) during the nearly 15-year life of the system, according to NICS data. Of these checks — again based on NICS data — more than 1.02 million resulted in a federal denial, a denial rate of less than 1 percent.

Many experts have praised the system’s effectiveness in regulating the primary gun market, but its lack of jurisdiction over secondary and black markets is a serious concern.

A lack of follow-up on NICS-related perjury (since lying on the NICS application, aka ATF Form 4473, is a federal crime) and deficiencies in mental-health data within the NICS system are also regarded as weaknesses.

Market watch

NICS denials come with consequences.

Closing legal doors to the world of gun ownership encourages troublemakers to find other, less-ethical ways to acquire firearms, critics of the system argue.

Though NICS prevents gun sales to certain prohibited classes via the primary, legal market, it has no impact on the black market or secondary markets. Secondary markets are cases in which individuals legally resell firearms to people whom they assume are eligible for gun ownership.

“If you simply turn, let’s say, a felon away at the gun store and he then goes out and simply buys the gun in a back alley, I’m not sure you’ve really accomplished anything,” said Robert J. Cottrol, professor of law and history at The George Washington University Law School.

Cottrol, a self-professed “somewhat high-profile supporter of the right to keep and bear arms,” said the U.S. doesn’t have the best track record when it comes to fighting domestic black markets.

“Where there’s a large demand, we end up having willing suppliers, and… the state of the law doesn’t seem to make that much difference,” he said.

James B. Jacobs, a professor at the New York University School of Law, said the secondary market was another area of risk.

“Here’s the situation: I have a gun, I sell it to you, right – there’s no background check, you’re not background checked in a secondary market or in a private sale,” Jacobs said during a phone interview.

Jacobs, a professor of criminal law, said that this problem could be solved if Congress required NICS clearances or permits for the purchase of guns from secondary markets or forced secondary sellers to run potential buyer identification information through NICS.

But he said NICS isn’t to blame.

“This is a failure of the…overall regulatory system not to require you to get a background check.”

To tell the truth

Another problem goes back to the first step in the purchasing process: the application.

Technically, since applications are only denied after disqualifying data are detected, any rejected applicants should be subject to arrest as perjury suspects, said Stephen P. Halbrook, a private-practice attorney and gun-control scholar who has done research and litigation on NICS.

“There’s thousands and thousands of people who are turned down because they have criminal records and, yet, they’re not prosecuted,” Halbrook said

in a phone interview. “Just a handful are prosecuted for making false statements when they fill out the forms for the purchase of a firearm.”

Halbrook, a Second-Amendment advocate, said the burden of prosecution in such cases falls on the U.S. Attorney’s office, but the ball has consistently been dropped.

“When the subject is brought up,” he said, the normal response is usually one of complacency and laziness. Officials accused of not following through on faulty applications cite case overloads, the difficulty of prosecuting perjury and the positive note that gun sales to prohibited parties were stopped, he said.

For Halbrook, there are two acceptable explanations for falsified forms: some would-be buyers are wrongly accused and others are the just naïve.

The first category, according to Halbrook, is the result of improper record keeping.

“Sometimes the person might be arrested for a felony but only convicted of a misdemeanor, so if the record only reflects the arrest and not the final judgment or disposition, than the record itself is deficient,” he said.

The second, he said, is the stuff of honest mistakes.

“There may be cases where individuals legitimately don’t know the legal status of their record,” he said.

Halbrook views these kinds of cases as exceptions — not the rule.

“Not every case merits prosecution, but it’s gotta be more than what we’re getting.”

Privacy versus public safety

Mental health is also a significant issue in the applications process, Halbrook said.

The NICS Improvement Amendments Act of 2007 was an attempt to remedy the problem by improving the flow of mental-health data to NICS administrators. This, in turn, was meant to reduce the number of individuals with adjudicated mental health issues — another NICS Index disqualifier — from purchasing firearms.

Critics say that increased transparency in mental-health-records is necessary for NICS to be more effective.

Halbrook said “the states have been very reluctant to disclose” mental-health information.” He cited the Virginia Tech shooter, who killed more than 30 people on the Blacksburg campus on April 16, 2007, as an example of an individual who should have been screened out during the NICS process.

Professor Jacobs of NYU agreed with Halbrook.

Jacobs, co-author of a 2011 working paper titled “Keeping Firearms Out of the Hands of the Dangerously Mentally Ill,” said that state negligence in providing such records to NICS administrators was to blame.

Looking ahead

Secondary-market concerns could potentially be solved through the expansion of NICS to include secondary sellers, Jacobs said. But universal background checking “would be difficult to enforce.”

‘We don’t know what the degree of enforcement would be,” he said. “We don’t know what the penalty would be for avoiding the system.”

The public would have to cooperate to make it work, Jacobs said – and some would. ”I think there would be a lot of noncompliance, but we don’t know the extent of noncompliance.” Jacobs said. “The people who are most law-abiding and who basically follow the law would comply.”

The Manchin-Toomey amendment, which stalled on the Senate floor in April, attempted to deal with some of these concerns. The measure sought to expand background records checks to include some secondary markets. All online and gun-show sales, for instance, were covered. Sales among friends, family and neighbors remained exempt from NICS checks under specified conditions. The amendment also barred the creation of a national gun-owner registry.

Rather than blaming the system for the current state of U.S. gun-control affairs, Cottrol suggested that the real problem with the current approach is the way we’re looking at the problem in the first place.

“One of the things we never seem to ask in the gun control debate is what economists might term the ‘opportunity-cost issue,’’ Cottrol said.

It comes down to the question of whether spending “less time on the question of who’s getting firearms” and more time on targeted punishments for repeat offenders who use guns in criminal acts would be a better fix, he said.

Cottrol suggested that a paradigm shift might bring us one step closer to solving the gun-control problem.

“It’s not a matter that Mr. and Mrs. America buys a firearm and then all of a sudden wakes up and decides to commit murder or to rob somebody,” Cottrol said. “What we have are career criminals who regularly go out and misuse firearms, and I think the way to cut the tragedy of gun violence is to concentrate our energies on that population.”