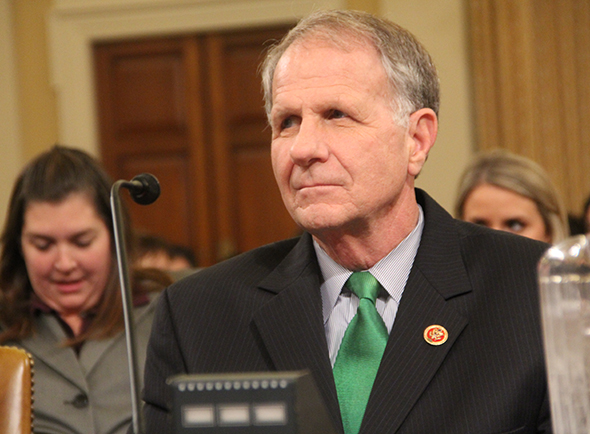

Rep. Ted Poe, R-Texas, a former judge, called Houston a “hub” of sex trafficking. Bryan Lowry/Medill

WASHINGTON — Failures in the foster care system put children in Texas and across the nation at greater risk of falling into the sex trade, activists and lawmakers asserted Wednesday on Capitol Hill.

Child welfare advocates and U.S. House members from both parties told the Ways and Means Subcommittee on Human Resources that foster care youths are targets for sex traffickers. They called for reforms in both the child welfare system and in how law enforcement handles the problem.

At the hearing Wednesday, U.S. Rep. Ted Poe, R-Texas, said he would introduce legislation to create a grant program to help child welfare agencies carry out rehabilitation programs for victims of sex trafficking, paid for in part by fines levied on people convicted of trafficking and other child exploitation crimes.

Poe, a former Harris County prosecutor and judge, lamented Houston’s status as “a hub for this despicable crime.”

“Many people think this is a myth, not a fact, and that it couldn’t happen here. But the problem is very real, especially amongst vulnerable youth in the child welfare system,” Poe said in testimony before the panel.

In Texas, more than 100,000 children between the ages of 7 and 17 go missing each year, according to a 2012 Texas legislative report on trafficking. The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children estimates that 60 percent of children likely to be victims of sex trafficking have run away from foster care or group homes.

They are easy targets for traffickers because of their lack of a strong family support system, said Kendra Penry, director of programs for the Houston Rescue and Restore Coalition.

This problem was exemplified at the hearing by 24-year-old Wilthelma Ortiz, who was part of the California foster care system before spending several years in the sex trade. “No one looks for us. No one keeps us on their radar.”

Ortiz said the instability of life in foster care makes it easy to accept life in the sex trade.

“Foster care creates an ever-changing environment of youth having to adapt to strangers making their life decisions,” Ortiz said. “Many foster children and youth switch placements so often that it doesn’t allow us to gain skills to acquire or sustain relationships.”

Patrick Crimmins, a spokesman for the Texas Department of Family and Protective Services, which oversees child welfare in Texas, said his agency was working hard to protect Texas youths from trafficking — including working closely with the Texas branch of the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children to determine best practices for locating missing foster children.

The state’s child welfare division, Child Protective Services, looks for regional trends in missing children, has developed contracts with a Houston-area facility to treat children who are victims of trafficking, and is “on the Texas Human Trafficking Task Force,” he said, “and will be working with the attorney general’s office to develop training for CPS investigators, conservatorship workers and foster care workers to recognize the signs and symptoms of what would make a child vulnerable to being trafficked.”

But Ashley Harris, an advocate with Texans Care for Children, testified that Texas’ foster care system is plagued by case overload and insufficient training. Harris served as a caseworker for CPS from 2006 to 2011. She spoke with regret about her inability to help a young woman who had been shuffled between 20 foster placements by age 17. The young woman ran away multiple times and slipped into prostitution, but Harris said she failed to recognize the signs.

“I just didn’t have the skills and training,” Harris said in an interview.

In 2013, caseworkers in Texas had an average load of 32 cases. Child welfare experts recommended between 12 and 15, Harris said. In the last legislative session, lawmakers took strides to improve these rates, appropriating money to hire 900 additional caseworkers.

But the state’s child welfare system has remained under fire: A federal class-action lawsuit filed in August against DFPS alleged widespread abuse and neglect in foster homes across the state.

Crimmins denied the allegations in the lawsuit. He said every child-placing agency in Texas must be licensed and is regularly monitored by the department. “We also conduct unannounced inspections of [child-placing agencies] and foster homes,” he said.

One of the challenges in combating the sex-trafficking problem is the lack of reliable data, said Penry of the Houston Rescue and Restore Coalition. The National Human Trafficking Resource Center received 1,130 calls to its hotline from Texas between January and June of this year, nearly 8 percent of its calls for the entire nation during that timeframe.

U.S. Rep. Lloyd Doggett, D-Texas, the ranking member of the subcommittee, said children who get involved in prostitution need to be treated as victims rather than criminals. Several activists at the hearing said many states do the opposite.

In Texas, Penry said, the laws governing youths and prostitution are often at odds. While a person 14 or older can be prosecuted for prostitution, she said, the law also stipulates that prostitution of minors must be considered sex trafficking.