WASHINGTON – Education reformers have pushed long and hard for curriculum changes, but the focus may be shifting to grading practices. And for parents in many school districts, that means bragging that your child is a straight A student could become a thing of the past.

Enter standards-based grading. This system measures a student’s proficiency in particular subjects instead of handing down a traditional letter grade for each course. While the move toward standards-based curriculum has picked up steam in recent years, experts said grading practices have remained largely unchanged.

Thomas Guskey, a professor of educational psychology at the University of Kentucky, has written several books about how school districts can best adopt standards-based grading. With the implementation of the Common Core curriculum standards, it’s now time for states and school districts to update grading practices.

“I think that the reporting [grading] has been the one element in these reforms that’s been ignored,” Guskey said. Most likely that’s because it is left up to individual districts or schools to carry out. “Common Core and assessment programs are statewide.”

How schools go about grading students does not fall under state mandates, but some states are driving a new focus on reform of grading and reporting procedures.

Standards-based grading gained notice at the elementary level in the mid-to-late 1990s. Soon it will be mandated at the middle and high school levels in states such as Oregon and Maine.

Ken O’Connor, an education consultant and proponent of standards-based grading, said that it provides a profile of student achievement so parents, teachers and kids can see a clear picture of strengths right next to areas that need improvement.

“Rather than it being an accumulation of points, it makes it clear that school is about learning,” O’Connor said.

Some school districts are still trying to catch up.

Educators in the Virginia Beach City School District implemented standards-based grading across all 56 elementary schools this school year, after running a pilot program for the past few years.

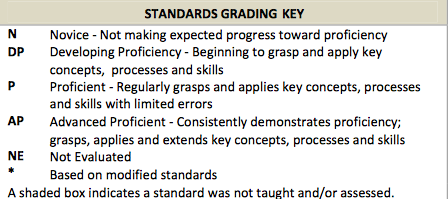

Instead of traditional letter grades in subjects such as math, English or science, students in grades kindergarten through 5th now get proficiency scores – N for Novice, DP for Developing Proficiency, P for Proficient and AP for Advanced Proficient – in specific, narrow areas of study. For example, the report card would give a proficiency score for fractions, multiplication, and so on.

Krista Barton-Arnold, director of elementary education at Virginia Beach City Public Schools, said school officials started talking about making the switch more than five years ago. The development and implementation of new reporting standards, however, takes time.

“Traditional report cards are from the early 19th century and our education system no longer aligns with that,” she said.

But doing away with As, Bs and Cs isn’t easy – Barton-Arnold said there was initial pushback from Virginia parents, who wondered why the traditional report cards they grew up with were no longer good enough for their children. Teachers, who have to put in more work to give explicit feedback for students, also had concerns.

The upside, she said, is that “teachers know students far better than they ever have before” and follow curriculum more tightly because each standard is aligned.

O’Connor agreed and said the increased workload ultimately comes down to “working smarter, not harder.”

For parents, the bonus is that they get report cards with more information and detailed ways to help their children succeed. In many districts, the confusion has stemmed from schools not communicating the changes clearly enough to parents.

“They miss Honor Roll and Principal’s list, that’s probably my number one complaint,” Barton-Arnold said. She added that the district isn’t looking to expand the system past the elementary school level just yet because it gets complicated with grade point averages and college admissions.

In an op-ed on JumpRope, an online education blog, teacher John D’Anieri wrote, “The real question is not whether such systems work, they do, but whether our communities are willing to deal with the implications of a much more honest system.”

But there are challenges

Guskey, though a supporter, is also quick to point out shortcomings, particularly at the secondary level where curriculum and courses are varied.

“All second-graders are studying the same thing, which is not true of all sophomores in high school,” he said. Guskey said it is a movement that typically begins at the elementary level and works its way up in a district.

O’Connor, however, believes it’s most important in high schools, where the grades are high stakes.

“High school teachers have mashed together achievement and behavior,” he said, which leads to inflated grades because a student “smiles sweetly, colors between the lines — and then falls on their face in college.”

With standards-based grading, academic and behavior scores are reported out separately.

It’s difficult to say exactly how many school districts have made the move to standards-based grading systems – or plan to – because the data aren’t immediately available. But it’s clear the push is there.

“Schools have to come to this when they’re ready,” O’Connor said, “when they realize there are deficiencies with traditional reporting and grades.”