WASHINGTON — The Internet of Things is here.

Americans are adapting to a world where virtually everything – from cellphones and cars to washing machines and refrigerators – is going to be connected to the Internet or a network. Many of these devices will — and do — “talk” to one another via tiny sensors that function almost like human senses, logging information such as temperature, light, motion and sound.

Theoretically, the sensors could allow a new refrigerator, for example, to send an alert to a mom’s smartphone whenever her household is running low on milk. This concept of device conversation is known as the Internet of Things. The technology will make life easier, but it also means more people are vulnerable to device malfunction or hacking.

Experts and government officials acknowledge the transformative power of the Internet of Things. But authors of a White House report, released this May, on the effects of big data – including all of the information that devices collect – are also concerned about the potential for privacy abuses that come with this technology.

These innovations raise “considerable questions about how our framework for privacy protection applies in a big data ecosystem,” the report said. And the rate of development is only picking up pace.

Deepti Rohatgi, a policy advisor at Lookout, a mobile security firm in San Francisco, said that each day more than 30,000 new apps are created for almost a billion mobile devices. Further, a 2011 report from Cisco Systems, a corporation that designs, makes and sells computer networking devices, projected that by year 2020, some 50 billion devices will be connected to the Internet or a network, or an average of just under seven connected devices per person.

Rohatgi said that one of the ways to ensure information security is to follow the example of Google Glass, a wearable computer that looks like eye glasses but works like a smart phone.

In 2013, Glass launched an “Explorer Program,” which allowed individuals – and specifically developers and hackers – an opportunity to test the prototype. Not only did this give Google a chance see how the public would react to the technology, it also allowed people with the technical know-how to alert Google to potential privacy problems they found in the new product.

That’s exactly what happened, Rohatgi said.

“Lookout got a hold of a Google Glass and we found a vulnerability with some of their software. We reported it to Google, and they patched it immediately,” Rohatgi said. “That’s a great example of how they were willing to share their technology with a group of hackers to say, ‘Help us find what the problems are before they’re released to the public.’”

The White House report cited several examples of how tech innovation and big data are being used.

Lights can now detect sound, speed, temperature and carbon monoxide levels from parking lots, schools and public streets; vehicles can record driving data that can be used to build better and safer transportation systems; and some home appliances can tell owners when to dim lights even when they are thousands of miles away.

Most of the data these devices collect is innocuous. But there’s still a chance, if small, that a third party could hack in and get a very detailed picture of its user’s life. Worse, it’s possible that a malfunction, with say a “smart” toaster, causes a fire when no one is home, or a malicious person hacks into a car traveling on the interstate at 70 mph.

“Once the Internet of Things is fully blossomed, there are going to be billions of devices with billions of sensors, and having a human review how every piece of software touches those sensors – it’s impossible,” Rohatgi said.

And because it’s impossible to review all of that code, conversations between inventors and developers are crucial, she said.

“Talking to folks who are really familiar with how these devices can be used for harm, educating them on what good practices are, what are best practices, and just having a dialogue with people” before a product is released is “incredibly important,” Rohatgi said.

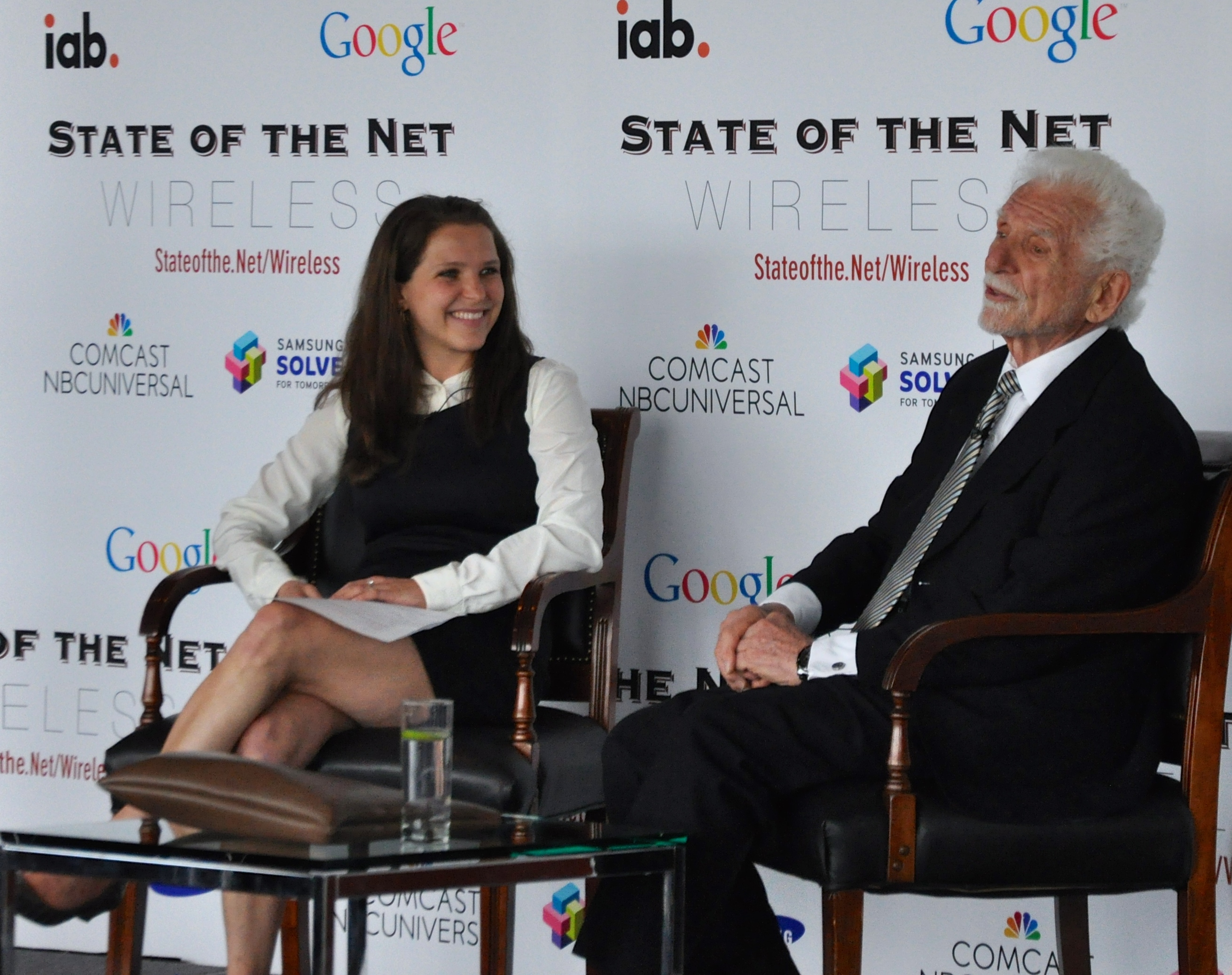

April marked 41 years since the world’s first mobile phone call was made. Martin Cooper, who conceived the idea while working for Motorola in the 1970s, led the team that ultimately developed and marketed the cell phone.

Despite privacy concerns, Cooper remains optimistic about the future of the Internet of Things. “We are most productive when we use wireless technology,” he said Monday at a mobile net conference in Washington.

Cooper cited poverty, healthcare and education as three major worldwide problems that can be solved by continued innovation. “In each of those areas, we are on the verge of revolutions.”