WASHINGTON – Does privacy mean the same thing today as it did a decade ago?

The director of the National Security Agency insisted Tuesday that Americans must change the way they think about privacy in the 21st century.

The NSA has faced heightened scrutiny since last year when agency contractor Edward Snowden leaked highly classified documents revealing the scope of government surveillance techniques.

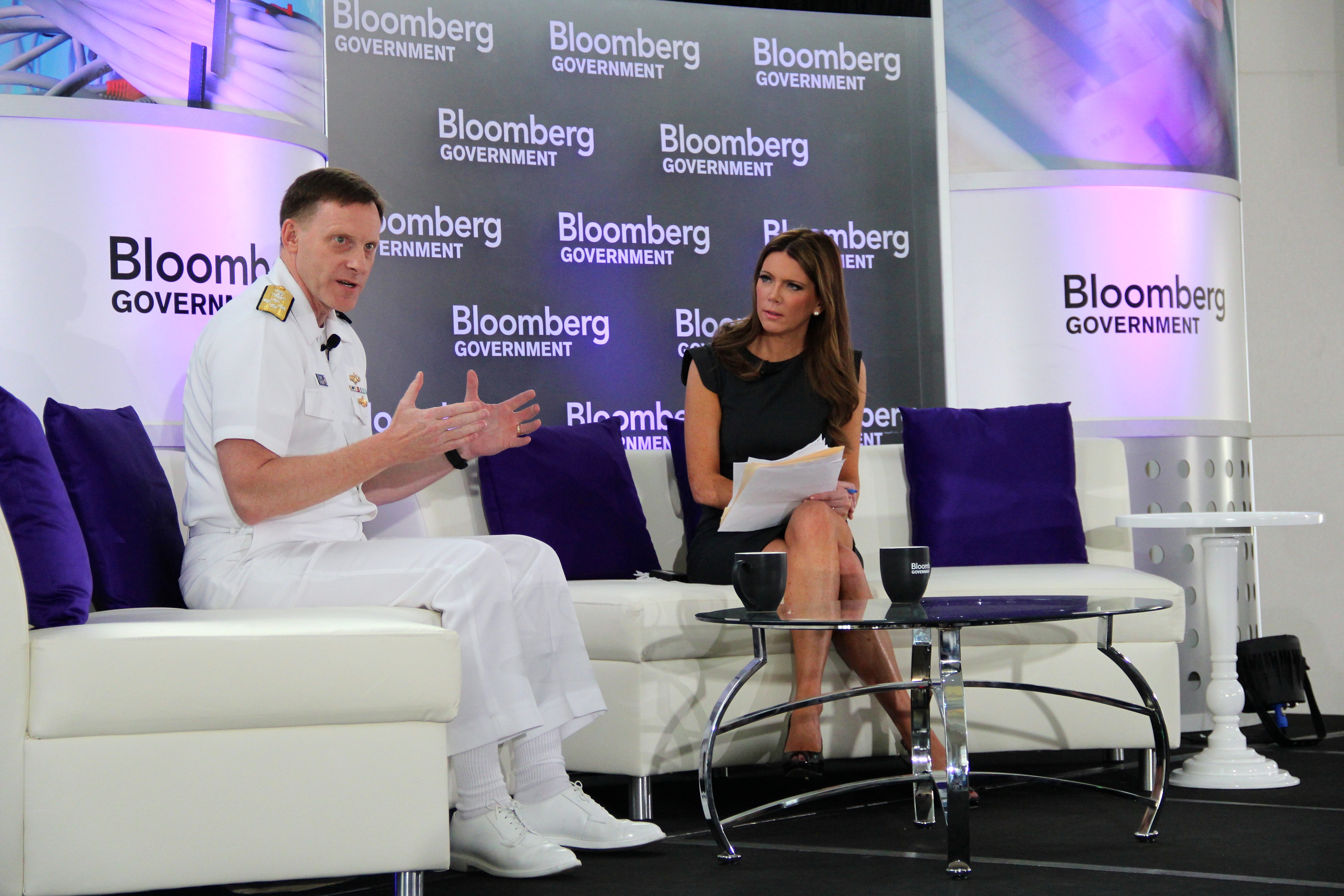

Speaking at a Bloomberg Government forum, Adm. Michael Rogers, who has served as the director of the NSA since April 3, addressed the Snowden leaks as well as what potential cyberattacks mean for both U.S. business owners and everyday citizens. In doing so, Rogers framed the purpose of the NSA in broad terms, encouraging Americans to view its actions as only one part in a larger discussion of privacy.

So what does the NSA do?

The NSA is primarily responsible for ensuring the security of U.S. government information. It also collects, decodes and analyzes information from other nations for counterintelligence purposes.

Rogers – as director – is “charged with generating knowledge and insight that helps this nation understand the world around it,” he said. Whatever it takes to increase “our ability to forestall the attempts of others to do harm on us, our interests and our allies” is his job.

If the agency believes people intend to attack the U.S. or its allies, the NSA has the capability to track them through means such as facial recognition software or cyber bugs that hack into cell phones and email accounts and download data.

Is that always legal?

“Every review from the outside world to date has come to the conclusion that there has been no systematic violation of law or policy on the part of the National Security Agency,” Rogers said.

He did, however, draw a crucial distinction between tracking foreigners and tracking U.S. citizens.

“We don’t do this for U.S. persons. Why? Our mission at the NSA is very explicit: Foreign intelligence and information assurance.” That is, protecting confidential information, which can include everything from bank routing numbers to intellectual property.

“If we have to do anything involving a U.S. person, there are specific legal constraints we must comply with,” Rogers said. “We can’t legally do that.”

“We have to assess the situation, and we have to get a legal authority or justification to continue.”

What does Rogers think of Snowden’s actions?

Rogers did not watch NBC’s interview with Edward Snowden last week, he said. But he caught later excerpts of it.

“He believes in what he’s doing. I don’t question that,” Rogers said.

“I believe it was illegal,” Rogers said of Snowden’s actions. “He stole sensitive information that he had been entrusted with.”

“We cannot function as a society if every one of us unilaterally decides, I’m right, everyone else is wrong, and I’m going to disregard the law and decide what I’m going to agree to adhere to and not going to adhere to,” Rogers continued.

“Be part of a dialogue. If you believe in this, use the powers of the law and the structures of our society to make your case.”

The chaos that would stem from a person doing otherwise, he said, “just comes across to me as incredibly arrogant.”

What should U.S. corporations be doing to make sure their information is secure?

Executives need to be asking, “What do I need to do to maximize my detection capabilities so I can find out very early if someone’s [hacked in] there, and then quite frankly, what do I do about it?”

Concerning legislation that would mandate cybersecurity standards for businesses, Rogers said:

“I am a proponent of legislation that would set up a structure for the corporate world to share information and for us on the government side to share information with our corporate teammates as we try to deal with this,” Rogers said. “Because coming together as a partnership is where we can be very powerful.”

Why is cybersecurity necessary?

“One of the challenges of being one of the largest, most powerful nations in the world is there are a lot of people out there who don’t have our best interests at heart,” Rogers said. “There are groups and individuals out there who, if they had their way, we would no lolnger exist as a nation.”

But potential threats do not mean U.S. citizen should automatically give up some of their rights.

However, “we do have to acknowledge that that threat exists. It’s not something we’re making up. We have lost, and our allies have lost, literally thousands of citizens in the last decade from individuals who have and continue to attempt to generate threats to take down our citizens.”

The big question:

“What does privacy mean in the world we live in today?” Rogers asked.

“The idea that you can be totally anonymous in the digital age is increasingly difficult to execute,” he said.

So, no, in a post 9/11 world where 30,000 new applications are created each month, the old idea of privacy no longer exists.

And to define a new one, people need to be asking what they are comfortable with and what they can’t go along with, Rogers said. The answers will help inform debate surrounding U.S. cyber policy.

“In the world we’re living in, increasingly, by choice and by chance, we are forfeiting privacy at levels that I don’t think as individuals we truly understand,” he said.

“Whether it’s cameras that are out on the street, whether it’s every one of your personal digital devices that are constantly asking you, ‘Can I share where you are?’ Or whether it’s the questions that we get asked in trying to do business, ‘Hey give me your Social Security number.’”

“Cybersecurity,” Rogers said, “is something that is foundational in the world we’re living in.”