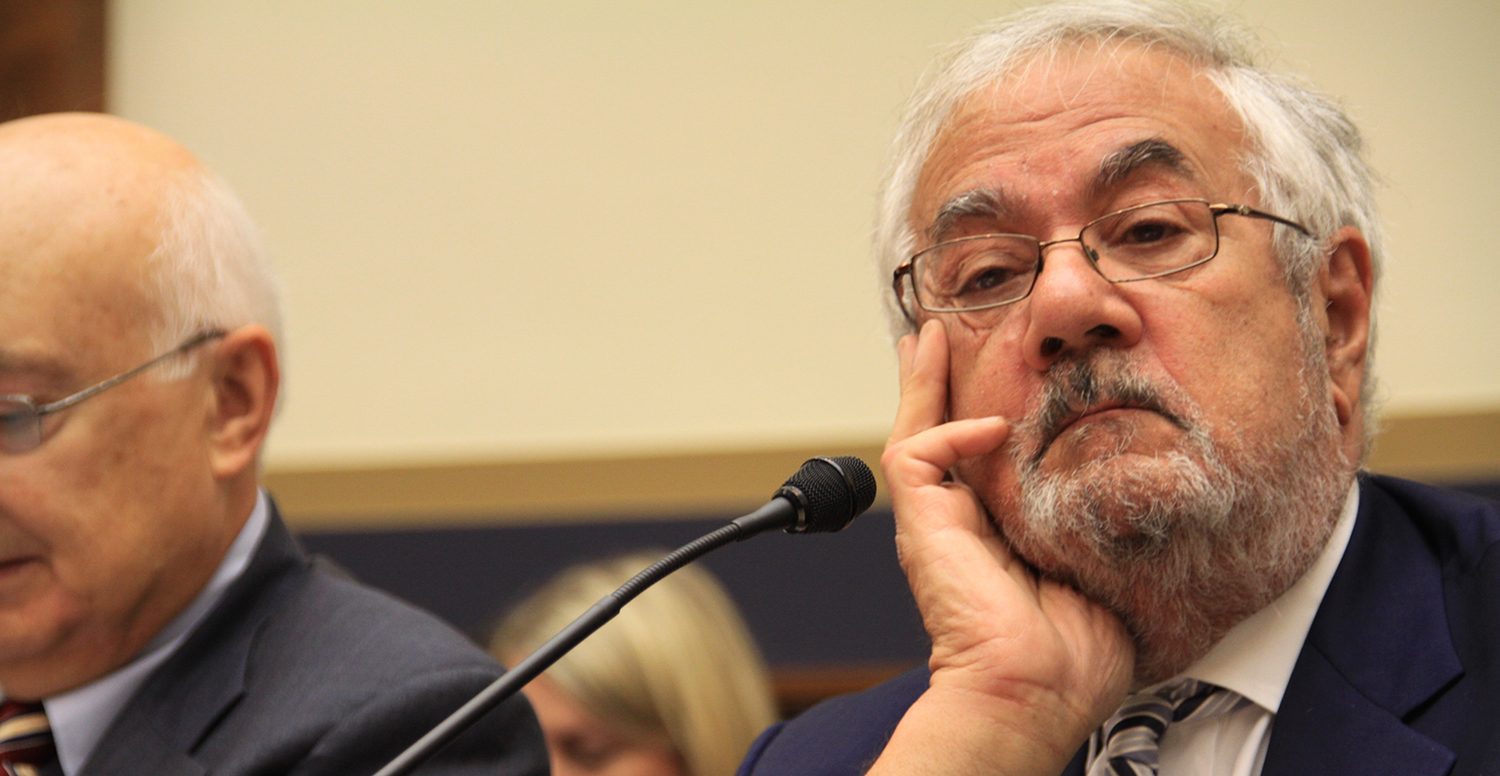

WASHINGTON — Former Rep. Barney Frank insisted Wednesday that the Wall Street reform law he co-authored offers a way to end government bailouts, but Republican critics still say it fails to resolve the problem of “too big to fail.”

“The Dodd-Frank Act is clear: not only is there no legal authority to use public money to keep a failing entity in business, the law forbids it,” Frank said in his prepared remarks for a House Financial Services Committee hearing.

“But no one can be sure that the firms will not find other ways to get in trouble,” said Frank, the former chairman of the panel that took his testimony. “If they do, the death panels take over, and the institutions die, with no taxpayer burial costs.”

The Dodd-Frank Act is a package of financial reforms that aimed to curtail Wall Street wheeling and dealing and improve the regulatory system which took part of the blame for the financial meltdown in 2008.

Under the new law, regulators can designate nonbank companies that are “systematically important” – that is, so big that it’s in the interest of the financial system that they remain viable. Once “designated,” such institutions face tougher scrutiny from the Federal Reserve.

Among the businesses that have been so designated under the law are American International Group Inc. and General Electric Company’s financing arm GE Capital Corp.

“The businesses hate the idea of being designated,” Frank said at the hearing, though he was not singling out a specific company. “Instead of being advantaged, they think it is a curse.”

However, critics of the law said such a designation would only create the impression that the government would bail out some companies in the event of failure because of their large presence.

“The Dodd-Frank Act further entrenched the problem of ‘too big to fail’ by giving regulators even greater control over our financial system and a virtually unlimited pot of taxpayer money to bail out financial institutions when regulation inevitably fails,” a GOP-drafted report released prior to the hearing asserted.

When a big financial firm collapses and is unable to pay debts, the 2010 law gives regulators the authority to assist the company’s liquidation with the option of using an “Orderly Liquidation Fund” to make loans to the firm.

“What the law says is you may have to pay some of the debts…” Frank said. “But first of all, you put them out of business and you put them into the receivership. And then you get the money back.”

The Dodd-Frank Act, enacted by a Democratic Congress, created new federal regulatory agencies, including the Financial Stability Oversight Council to supervise systemic risks, and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau which aims at predatory practices in the banking sector.

It also imposes rigorous rules on financial institutions’ trading activities and capital levels. However, many feel frustrated by the slow pace of implementation.

Frank, who represented a Massachusetts district, retired two years ago. But the Republican-led House banking committee has been battling to revise the law almost since its inception.

“By the end of this Congress our committee then would have repealed Dodd-Frank’s greatest sin of omission – its failure to do anything about housing finance reform – and its greatest sin of commission – enshrining bailouts into law,” Committee Chairman Jeb Hensarling, D-Texas, said recently. “And day-in and day-out, you can rest assured we will continue working to relieve our economy from the burden of growth-choking and job-killing red tape.”