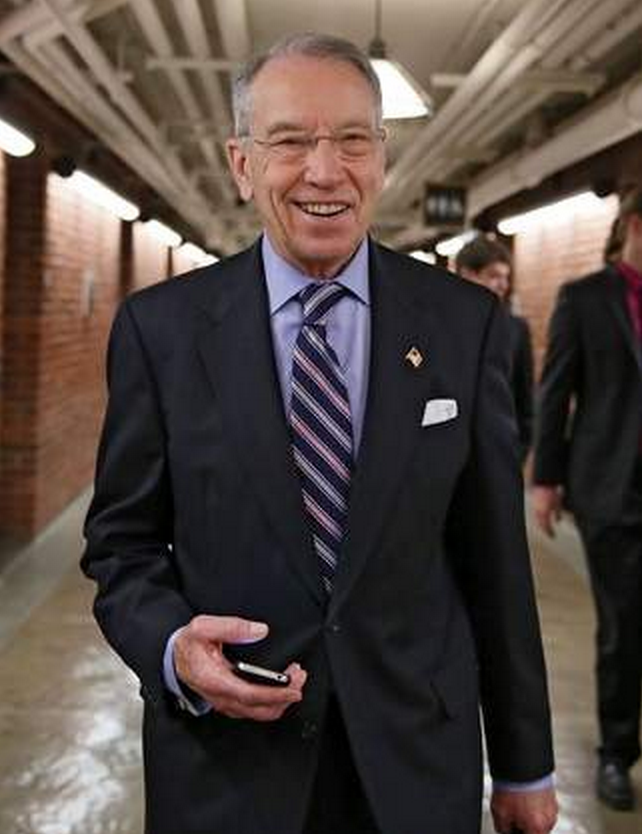

WASHINGTON – On a Thursday 31 years ago, first-term Sen. Charles Grassley smelled a rat. An analysis of the Reagan administration defense budget that revealed absurd spending had been leaked to the press. And Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger wasn’t letting Grassley meet with the man who had done the analysis.

Grassley, R-Iowa, drove to the Pentagon in his orange Chevy Chevette to get to the bottom of the $659 ash trays, $750 toilet seats and $6,000 arm rests that were being installed on new Air Force planes, according to Grassley biographer Eric Woolson.

This was one of Chuck Grassley’s first experiences standing up for whistleblowers but it would not be his last.

He’s still around as a member of the 113th Congress – a group that won’t be remembered for compromise and bipartisanship. But one cause has rallied support on both sides of the aisle: protection of federal whistleblowers.

As the top Republican on the Senate Judiciary Committee, Grassley has emerged as a bulldog, digging in to safeguard federal workers who report wrongdoings at their agencies.

His three-decades-old support of bipartisan protection laws is unparalleled, whistleblower allies in Washington say. And with a possible shift in power to Senate Republicans, his watchdog role could become even more significant.

A whistleblower is someone, often a government employee, who exposes a person or organization for illicit activity. Historically, some agencies have retaliated with push-back ranging from firing to more subtle harassment that is often difficult to prove.

Robert MacLean, one of these whistleblowers, has had Grassley’s support in an 11-year legal battle.

“He has been sort of the Godfather of the whistleblower protection law,” said MacLean, a former Transportation Security Administration air marshal. “He and his staff have been following my case for years.”

Grassley filed an amicus brief to the United States Supreme Court with Sen. Ron Wyden, D-Ore., and Reps. Darrell Issa, R-Calif., Blake Farenthold, R-Texas, Stephen F. Lynch, D-Mass., and Elijah Cummings, D-Md., on behalf of MacLean.

MacLean disclosed a text message to the media in 2003 that said that TSA air marshal missions were being canceled for some domestic flights.

In the years following the September 11 attacks, federal air marshals were embedded on passenger flights for extra security. MacLean said he believed removing these federal agents from flights was a threat to public safety. He received notice saying that he had disclosed sensitive security information and was later fired.

MacLean argued that his disclosure was protected under the 1989 Whistle Blower Protection Act that Grassley helped pass. The Supreme Court has agreed to hear his case, MacLean v. Department of Homeland Security, this fall.

MacLean’s attorney, Tom Devine of the Government Accountability Project in Washington, has worked with Grassley on improving whistleblower legislation. He disagrees with many of Grassley’s ideological stances but applauds his willingness to roll up his sleeves in Congress.

“He won’t let a partisan hidden agenda comp the facts,” Devine said.

Grassley’s conservative positions are frequently at odds with Democrats in the Senate. On whistleblower issues however, he has teamed up with Democrats such as Carl Levin of Michigan to pass the Federal Whistleblowers Protection Act, also known as the WPA.

Grassley has spent years in both the Senate minority and majority but hasn’t wavered based on shifts in the Washington landscape, according to Danielle Brian, executive director of the Project on Government Oversight.

“That doesn’t happen very often,” Brian said. “In that case, Sen. Grassley has been working in bipartisan and bicameral way.”

Grassley said he’s equally critical of federal agencies, regardless of which party in in power in the White House.

“I think my pushback comes equally under Republican as well as Democrat,” Grassley said in a telephone interview from Iowa.

As the ranking member of the Judiciary Committee, Grassley recently celebrated the 25th anniversary of the Whistleblower Protection Act that he authored. The law protects federal employees who report misconduct. Under the law, agencies accused of retaliation get called on the carpet before the U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board, which can level suspensions or fines.

Grassley’s bark in the Senate is backed up by his bite, according to Devine.

“In my experience, there are probably few members of Congress over the last few decades who are more feared and respected than Sen. Grassley when it comes to whistleblowers or oversight issues,” Devine said.

Grassley, who is not a lawyer but a farmer by trade, assigns his personal office staff to work on whistleblower issues and policy reform.

His Capitol Hill office often files amicus briefs on behalf of whistleblowers without attempting to attract media attention. Like other congressional staff, they issue news releases on behalf of whistleblowers but also go further. Grassley will often demand a briefing about the facts and threaten to call hearings to expose any retaliation if he doesn’t get answers, according to Devine.

“There’s very serious investigative work there. He’s the go-to office whether the whistleblower is famous, or whether it’s someone below the headlines,” Devine said.

Those who don’t heed these threats have seen an ornery side of the senator.

Grassley famously went to bat for David Graham, the epidemiologist who exposed the FDA for ignoring warnings that the pain pill Vioxx was killing people by causing heart attacks and strokes.

“That has happened so many times,” Devine said. “He’s our first option. He’s the go-to option to survive and get away with committing the truth.”

But not all whistleblowers have good intentions. “Some people come to grind an ax,” Grassley said. “Most claims are legitimate;” he said, “if they weren’t, I might be discouraged from putting so much work into the investigations.

His interest stems back to his time in the Iowa House of Representatives, but Grassley said he didn’t have the power to make a difference when he was a state legislator. When he reached the Senate, Grassley began working with whistleblowers in the Defense Department. He found so many problems that he expanded his interest to other federal agencies, he said.

Steven L. Katz, Washington attorney and whistleblower expert, has seen Grassley use his juice to make other senators jump. He said Grassley’s success has to do with his willingness to work with people on an individual level.

“It’s the populist view,” Katz said. It may now be something Iowans have come to expect and demand from their senator, he said.

Some Iowa Democrats have criticized the 81-year-old Grassley for operating on the Judiciary Committee while not having a law degree.

Rep. Bruce Braley, D-Iowa, who is running for Sen. Tom Harkin’s open seat in the Senate, scoffed earlier this year at the idea of Grassley’s potential new role on the panel.

“You might have a farmer from Iowa who never went to law school, never practiced law, serving as the next chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee,” Braley said in a video posted by a donor after a fundraiser in Corpus Christi, Texas in January and released by the America Rising PAC. “Because, if Democrats lose the majority, Chuck Grassley will be the chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee.”

Katz said Grassley’s lack of legal experience hasn’t slowed him down.

“It’s a David and Goliath kind of drama that he sees going on. He’s for David and thinks people in Iowa would appreciate that,” Katz said.

Most of cases that draw Grassley’s attention involve national whistleblowers, but he has worked on Iowa cases such as the Iowa State University misuse of research money from National Institute of Health, and the Veterans Administration Inspector General’s report of Iowa City VA Medical Center.

The problems for whistleblowers are far from over.

“They’re as welcome in a bureaucracy as skunks at a picnic,” Grassley said. “Most of them are just doing it because they’re dedicated public servants.”

Devine and the Government Accountability Project are lobbying to pass a series of whistleblower amendments to add more strength to the law during the lame-duck congressional session after the mid-term election.

Grassley is also looking to make changes going forward.

“We are going to make sure we get national security covered,” Grassley said about whistleblower protection.

Grassley also plans to look into court decisions where laws may need to be rewritten to deal with constitutional questions. Otherwise, he said he plans to do what he can as an individual to encourage support of whistleblowers and has confirmed that he will seek reelection in 2016.

As for the toilet seats, Grassley finally met with Chuck Spinney, the Pentagon employee who wrote the “Spinney Report” as the defense budget analysis came to be known. Spinney testified in front of a Senate Budget Committee, and was called the Pentagon Maverick on the March 1983 cover of Time Magazine. Two years later, the Senate rejected Reagan’s original defense budget and the country’s deficit was decreased. Grassley calls this a major accomplishment of his life.