Estimates suggest that despite efforts to reduce backlog, 100,000 untested kits remain

WASHINGTON—“At least if I comply with him, it will be a quicker death.” That’s what ran through Natasha Alexenko’s mind on August 6, 1993, as a man with a gun bent her over a railing in her Manhattan apartment building and raped her repeatedly. She was 20 years old.

“The rest is all a blur.”

When he released her, Alexenko somehow made it back to her apartment where her quick-thinking roommates took action. They refused to let her shower and brought her to a hospital where she underwent an invasive medical examination.

“That was the last thing I wanted to do, was sit there with him – with his fluids on my body,” she said. “My body was the crime scene.”

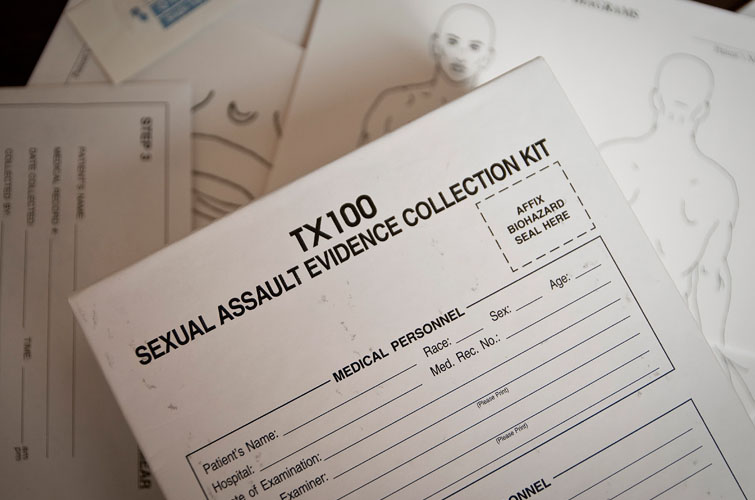

After hours of prodding, swabbing and plucking, a nurse examiner collected samples in a box. Alexenko had no way of knowing it, but that box would sit untouched for nearly a decade. Even when her case went cold, she still assumed all avenues to find her brutal rapist had been exhausted. She was wrong. And she’s not alone.

———-

Although DNA evidence is a case-solving mechanism for justice, with equal powers to convict or exonerate, 100,000 rape kits – possibly more – remain untested nationwide. That means the samples were never sent to a crime lab and a DNA profile was never generated. In other words, the kits weren’t used.

“Every [rape] kit is a person’s life who has been impacted by this violent crime,” said Sarah Haacke Byrd, the managing director of the Joyful Heart Foundation, a non-profit founded by Law & Order SVU actress Mariska Hargitay.

“That box, that bin, is an opportunity to provide justice for someone – to provide healing,” Byrd said.

According to Joyful Heart, most cities don’t track rape kits once they’re booked as evidence. The result has led to a national backlog, which some jurisdictions have tried to eliminate since the onset of the millennium.

In 1999, New York City identified 17,000 untested kits, a backlog it cleared in 2003 with the aid of private labs. Los Angeles cleared its backlog in 2011, testing 12,500 kits.

The numbers remain staggering nationwide: Tulsa – nearly 4,000 untested kits; Jacksonville – nearly 2,000; Las Vegas – over 4,000; Milwaukee – nearly 3,000; Portland – 2,000; and Seattle – over 1,000.

But an exact accounting isn’t possible and no nationwide law enforcement organization has released statistics either confirming, or refuting, the picture shared by Joyful Heart, an organization dedicated to helping rape survivors heal. The city-by-city numbers cited were obtained by Joyful Heart through public records requests in some instances, and through collaborations in others.

And there are two ways of thinking about what constitutes a backlog.

Joyful Heart argues that every kit collected as evidence should be tested, to enable DNA matches to existing or future criminal suspects. But some law enforcement agencies, like the San Diego Police Department, suggest otherwise – such as when a victim declines to pursue an investigation, or when an officer can’t determine whether the assault was a crime. According to Joyful Heart’s accounting, San Diego has nearly 3,000 untested kits, but SDPD claims to only have two as of mid-May, as reported by NBC San Diego.

And then there are the stores of untested kits still waiting to be found. Lockers that have somehow been forgotten.

An 11,000-kit stockpile was discovered in a Detroit police storage facility in 2009. To date, 1,600 of those kits have been tested with financial support from the National Institute of Justice, and nearly 1,300 have resulted in DNA matches. Those matches identified 288 potential serial rapists, linking to crimes in 31 states, as well as Washington, D.C.

That’s the power of DNA evidence, Sarah Haacke Byrd said. Not just finding names, but generating linkages.

Understanding the serial nature of rape remains key to preventing sexual assault, Byrd said, as perpetrators often become repeat offenders. Knowing this should be enough to convince the public of the value of testing all rape kits, she said, even if a victim chooses not to pursue an investigation, or if a suspect has already confessed. That suspect could be implicated in a similar crime somewhere else.

Testing a single rape kit can cost anywhere from $1,000 to $1,500. “But testing these kits isn’t just about the act of testing,” Byrd said. “Once you have evidence that is a link to other crimes, you are involving other people in that effort.”

Which is the best approach to combatting sexual assault nationwide, Byrd said: collaborative, “multidisciplinary efforts between law enforcement and communities.”

That premise is at the heart of a $41 million grant offered through the Department of Justice as part of its FY15 budget to encourage such partnerships. The Manhattan District Attorney’s office has pledged an additional $35 million in grant dollars to support fellow jurisdictions as they attempt to bring their number of untested kits to zero. (Those dollars were won as part of sanctions cases against French bank BNP Paribas.)

Time is of the essence. Twenty-four states and the District of Columbia have statutes of limitation in place so that rape charges cannot be brought after a certain period, ranging from three years to 20 years. Ending the backlog is an urgent endeavor, Byrd said.

———-

But it’s never too late to aid in the healing process, Alexenko said. Her rape kit got tested just months before the statute of limitations ran out, as NYPD worked through its backlog. She testified before a grand jury in a John Doe indictment: “They charged the [suspect’s] DNA and the clock was stopped.”

At that time, CODIS, the FBI’s criminal justice DNA database, didn’t offer a match for her rapist, but he was arrested four years later and returned to New York on a parole violation.

“They did a cheek swab, uploaded it into CODIS and it was a match,” she said. Victor Rondon was convicted in 2008 on eight counts of violent sexual assault.

“Everything I went through was not for nothing,” she said. “He’s going to be in jail until 2057.”

Her experience is proof of what can happen when a rape kit is tested – and what almost happens when it isn’t. “My kit was one of 17,000 kits in New York City that hadn’t been tested,” she said. It is worth noting that New York repealed its statute of limitations on rape in 2006.

A Long Island resident, Alexenko founded Natasha’s Justice Project to educate people about the backlog.

“But I can’t do this alone,” she said. “It’s going to take an army to get through all these kits. It’s going to take a lot of voices.”