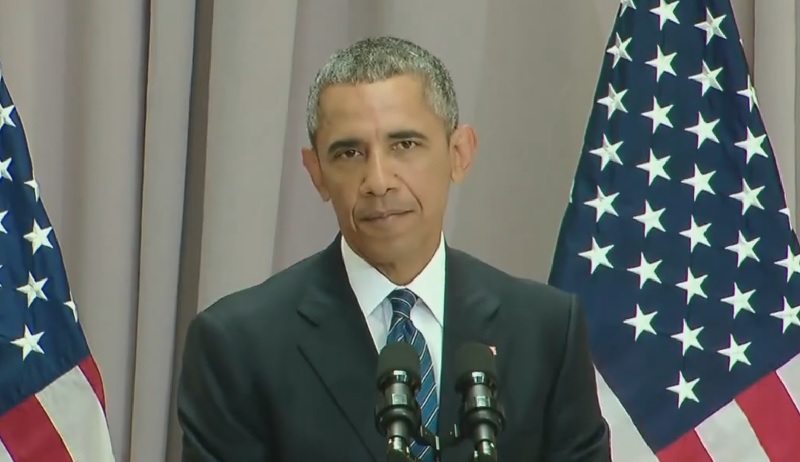

President Barack Obama may not need the approval of a reluctant Congress to commit the United States to the Iran nuclear deal after all.

According to legal scholars, the deal is technically more of a “political commitment” than it is a treaty. Therefore, a potential veto-proof majority in Congress that rejects the agreement might prove to be of little legal consequence in determining the fate of the pact. In a way, Obama has already committed the nation to abide by the Iran deal under international law — even before Congress has taken action on it.

The Obama administration “really like[s] this idea that the president has vast authority not to enforce the law,” Jeremy Rabkin, a law professor at George Mason University, told VICE News, referring to the Iran Nuclear Agreement Review Act of 2015, which gave Congress a say in reviewing the agreement after Obama signed the bill into law in May. “If that is plausible anywhere, it is probably most plausible in dealing with not just a foreign country, but a foreign country in sort of a quasi-military standoff.”

An aide to Sen. Bob Corker (R.-Tenn.), chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee and a principal sponsor of the review act, told VICE News in an email that Corker expects the administration to “adhere to the law that the president signed giving Congress the opportunity to approve or disapprove of the agreement.”

“Should Congress enact a resolution of disapproval when it votes in September,” Corker’s aide added, “the president would be prevented from exercising his national security waiver authority to suspend congressional sanctions and fully implement the nuclear agreement.”

In the US, a treaty requires the advice and consent of two-thirds of the Senate and ratification by the president. In contrast, the Iran deal — or the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, as it is officially titled — can be described as a non-binding international settlement that relies on domestic moral and political forces to hold the signatory countries to the agreement. But the use of such a political commitment in lieu of a treaty is not unprecedented.

This tactic was used at least twice in the 1970s. It was first used when President Richard Nixon and Mao Zedong, chairman of China’s Communist Party, established the Shanghai Communiqué to begin normalizing relations between the two countries. It was used again with the Helsinki Accords — perhaps the most famous use of the “political commitment” tactic — which encouraged stronger mechanisms for resolving international disputes, respect for human rights, and stronger territorial integrity protections between nation-states involved in the Cold War.

Related: An Iran Nuclear Deal Seems Imminent — And Congress Is Ready to Fight It

The Senate, in a bid to become more directly involved in the Iran negotiations and to alter the political and moral forces used to compel compliance between Iran and the P5+1 (the UN Security Council’s five permanent members — China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States — plus Germany), passed the Iran Nuclear Agreement Review Act in a 98-1 vote. The US House approved a companion measure.

The law prevents the president from waiving statutory sanctions while Congress reviews the deal. The review period is 60 days and commenced on Monday, July 20, the day after the State Department presented the agreement to Congress.

‘I used to think it was really inconceivable that two-thirds of each house would vote to override. I now think that actually might happen.’

After the act’s passage, however, the UN approved a resolution endorsing the Iran deal in late July. Though non-enforceable, the vote established that UN member countries, including the US, are committed under international law to follow the agreement. Because the US is a permanent member on the Security Council, Obama could have unilaterally blocked the resolution and waited for Congress, but he chose not to do so. Instead, the resolution will not take effect for 90 days to give Congress time to review the deal.

The UN resolution “makes the deal part of the US treaty obligations under the UN Charter,” Duncan Hollis, a professor of international and foreign affairs law at Temple University, told VICE News in an email. “The US has agreed under the Charter to obey decisions of the Security Council.”

It is “definitely not the norm” for the US to bind itself under international law before it is ready to follow the law at home, he added.

According to Hollis, Obama has entered the US into an agreement that functions like a treaty internationally — possibly without the consent of Congress — in an area in which many Americans would likely want lawmakers to have a say.

“It is a little bit troublesome,” he said, noting that if Obama ignores two-thirds or more of Congress, he could end up forcing a constitutional showdown. “I do think this is becoming a test case.”

Critics of the agreement are concerned that it will spark a nuclear arms race in the region, expose Israel to an unacceptable level of risk, and make it difficult to restore sanctions against Iran if it is found to violate the pact. They also argue that weak inspections protocols could effectively allow Iran to conceal a nuclear weapons program.

To thwart the deal, its foes will first need 60 Senate votes to choke off a filibuster, permitting a final vote on a resolution of disapproval. Obama has promised to veto such a resolution. Opponents of the deal would then have to secure votes of two-thirds of the lawmakers in both chambers to override his veto.

If Congress rejects the deal with a veto-proof majority, Rabkin suggested that the administration could theoretically rely on the president’s inherent authority as commander-in-chief and top diplomat to move the deal forward unilaterally. The Obama administration has not yet indicated that it would do so in this case, however.

A 1952 Supreme Court decision in the case Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer helped establish the contours of the president’s primary authority in matters of foreign policy. Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson’s three-part concurrence noted that Congress could approve the executive’s actions, maximizing the president’s authority, or object to his actions, minimizing his authority. The president can act independently if Congress remains silent, “but there is a zone of twilight in which he and Congress may have concurrent authority.”

“If the Congress votes by two-thirds in each house to say don’t do this, and then [Obama] does it anyway, it will be put up or shut up,” Rabkin said. “And [Congress] will shut up.”

It is also reasonable to assume that the Supreme Court would not intervene, he added, because the dispute would likely be viewed as a political question. This eliminates the potential of a judicial remedy if Congress objects.

“I used to think it was really inconceivable that two-thirds of each house would vote to override,” Rabkin said. “I now think that actually might happen.”

“I think it’s difficult, but not impossible, to override a veto,” New York Rep. Eliot Engel, who is the ranking Democrat on the Foreign Affairs Committee, remarked to the Washington Post late last month, speaking in reference to the nuclear agreement.

New York Democrat Chuck Schumer, the man who hopes to lead Senate Democrats in the next Congress, came out publicly against the pact last week. Shortly after his announcement, Engel and Rep. Brad Sherman of California, another Democrat on the committee, voiced their opposition to the deal as well.

These defections occurred after Obama made his case for why the deal presents the best option to avoid war in a lengthy speech delivered at American University last Wednesday.

“Without this deal, the scenarios that critics warn about happening in 15 years could happen six months from now,” he said. “By killing this deal, Congress would not merely pave Iran’s pathway to a bomb, it would accelerate it.”

Still in play is Sen. Bob Menendez (D-NJ), former chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee. A spokesperson from his office told VICE News that he has not yet decided whether he will support the deal.

In the event of a veto showdown, Hollis said that it is possible to reach a middle ground. Congress could agree to let the president move forward with the deal on the condition that Congress be permitted to monitor Iranian actions and come to its own assessment of what’s going on, independent of the process established by the agreement.

“That was what the Helsinki Commission was originally designed to do,” he said, referring to the government agency that was established to track compliance with the Helsinki Accords. This would “provide a congressionally-approved monitoring body in lieu of relying on executive branch representations of what was happening.”

Congress’s first vote on the Iran deal is expected in mid-September.