In the fall of 2011, the Obama administration unveiled its “Pivot to Asia” – a strategic “re-balancing” of U.S. interests from Europe and the Middle East toward East Asia.

The pivot meant the United States would expand and intensify its already significant role in the Asia Pacific, particularly in the southern part of the region. The fundamental goal underpinning the shift was the expansion of trade and military cooperation with Asia-Pacific nations that share U.S. concerns over – among other issues – China’s territorial claims.

China has asserted ownership of nearly all of the South China Sea and is building at least seven artificial islands in the key waterway. Parts of the region are also claimed by Brunei, Taiwan, Malaysia, the Philippines and Vietnam.

The balancing act that unfolded this summer between Vietnam, China and the United States highlighted the many complexities the United States still faces in effecting its “pivot” as well as the success of Vietnamese self-defense, which experts say is part of a broader trend of Asian countries re-arming amid rising territorial tensions.

“When China declares indisputable sovereignty, starts to seize islands, starts to build artificial islands, establish military outposts – all of this is part of establishing Chinese control and sovereignty,” said Marvin Ott, lecturer in East Asian Studies at Johns Hopkins University and public policy scholar at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars.

“When the U.S. and the early Obama administration decided on the ‘pivot’ or the ‘rebalance,’ that was a strategic decision that the United States would not acquiesce,” Ott said. “We in effect said, ‘The U.S. is not going to stand by and allow the South China Sea to become a Chinese lake.’”

Ott said this meant the United States was on the lookout for strategic cooperation from other countries in the region.

“You start looking at the map and start saying, ‘Okay now, who can we work with? Who can give us meaningful support as we undertake to stymie the Chinese?’” he said.

The latest strategic partner in the region? Vietnam.

“As you survey the countries of the region and you ask, ‘who in Southeast Asia is prepared to actually militarily resist the Chinese, if it comes to it?’ Vietnam looms very large in that picture,” Ott said.

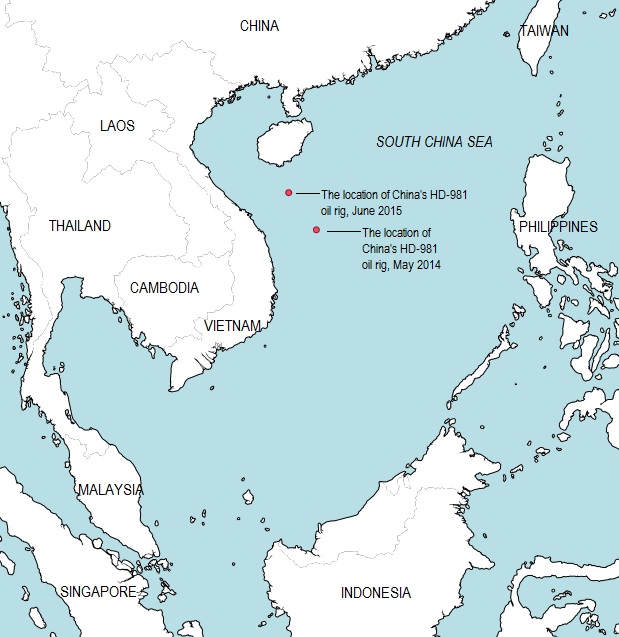

In June, China moved its massive Haiyang Shiyou 981 (HD-981) mega oil drilling platform into waters where the disputed exclusive economic zones of Vietnam and China overlap.

The arrival of the rig — more than 40 stories tall and the size of a football field — prompted daily clashes at sea between Chinese vessels sent to protect it and Vietnamese boats that tried to pierce the perimeter of about 12 miles the Chinese had established around it.

“It’s been described by some analysts as mobile sovereignty,” said Ernest Bower, senior adviser for Southeast Asia Studies and co-director of the Pacific Partners Initiative at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. “For the Vietnamese, they feel like when it’s towed offshore into what they view as their territorial waters, you do have a direct contestation of their sovereignty. It’s that significant in Hanoi’s eyes.”

“The fact that it’s been towed back into Vietnamese waters at this time could be seen as a warning by Beijing that just because you’re going to the United States at an unprecedented political level, doesn’t mean that we’re pulling up or letting up at all on our determination that this is our territory,” Bower said.

Last summer China moved the same rig into similarly disputed waters. The resulting backlash included widespread anti-China riots and protests across Vietnam, and one self-immolation.

“The rig arrived with up to 80 escort vessels and in the course of the ensuing confrontation, more than 100 Chinese warships, maritime law enforcement vessels, tub boats and fishing craft formed three protective rings around the HD 981,” said Carl Thayer, a Southeast Asia regional specialist who taught at the Australian Defence Force Academy.

“The first, previous deployment of that rig had a major effect on the Vietnamese,” said Ott. “It was really a sort of galvanizing moment for the Vietnamese leadership.”

“Last summer the Vietnamese were genuinely surprised by the aggression that Beijing showed by placing the rig off that coast,” Bower agreed.

Since the deployment of the rig in the summer of 2014, the Vietnamese have taken proactive steps at self-defense, upping defense spending and forging new strategic partnerships.

“The Vietnamese have… become pretty clear-eyed about the fact that the Chinese are going to say some things that are more conciliatory but the actions are going to continue to be very aggressive. So rhetoric and actions aren’t matching up, and the Vietnamese understand this.”

Less than one week after the redeployment of China’s oil rig in contested waters this summer, Vietnam received a new Kilo-class submarine from Russia – the fourth of an expected six submarines purchased as part of a deal Vietnam reached with Russia’s Admiralty Shipyards for six Project 636 Kilo-class diesel-electric submarines for $2.6 billion back in 2009. Under the agreement, Russia agreed to provide the submarines, train Vietnamese crews and supply necessary spare parts.

“They represent Vietnam’s version of a deterrent force designed to prevent China from accessing and operating in areas of the South China Sea,” Thayer said in an email. “If we leave aside all talk of a conventional war – fleet on fleet – the Kilos represent a strategic headache for China. Not only are naval combatants threatened, but Vietnam can strike the home ports from which Chinese warships operate.”

“The submarines have shown up at a time when Chinese military spending is doubled in the last four years. And in response, Southeast Asia’s military expenditures have also doubled at even a faster rate, over the last two years. And we expect that to continue to double for the foreseeable future. The planning on spending is enormous,” said Bower.

China has quadrupled its military spending in the past decade, jumping from $46 billion in 2005 to $216 billion in 2014.

But Vietnam’s military spending has more than quadrupled in that time too to over $4 billion, according to a report by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute – a further sign of the country’s determination to counter the rise of China’s larger military.

Vietnam is not alone: the Philippines and Brunei both doubled military spending in the past ten years, with Brunei’s defense budget jumping 28 percent in the last year alone to $528 million.

Indonesia has more than tripled its spending over the past decade, jumping from $2.1 billion to $7 billion, upping defense spending by an average of nearly $500 million a year for the past ten years.

In 2014, Singapore spent $1,789 per capita on its military, while Brunei spent $1,320 per person. For reference, the United States spent $1,891 per capita last year.

A full 18 percent of government spending in Singapore last year went toward its defense budget – nearly double the 9.5 percent the United States devoted to its military, and more than double the 7.3 percent spent by China.

In the face of such territorial tensions, the Vietnamese have not only sought to stiffen their defenses, but have taken diplomatic measures to solidify their strategic partnership with the United States. In July, the White House hosted the leader of Vietnam’s Communist part, Sec. Gen. Nguyen Phu Trong, the first top party and country leader ever to visit the United States.

“The Secretary General of the Vietnamese communist party – who was seen as conservative, hardliner, relatively pro-Chinese – is in the process of building a pretty warm relationship with the political security commercial leadership. And this represents a kind of sea change that’s going on in Hanoi,” Ott said.

“I think we’re in the midst of a pretty dynamic sort of strategic relationship here,” Ott added. “But how far it will go remains to be seen. For the Vietnamese, the balancing act that they have to perform is to pursue a strategic understanding cooperation with the United States without tipping over some point into really generating hostility on the part of China.”

So far, this Vietnamese balancing act – of building both defense and diplomatic ties with the United States without stepping on China’s toes – has seen short-term success: on July 16, China moved its billion-dollar HD-981 rig out of disputed waters, almost a month ahead of its scheduled departure on August 15.

State-run Xinhua news agency reported that China National Petroleum Corp, which operated the rig, gave no explanation for why the rig was leaving earlier, but the statement came just one day after President Obama called Chinese President Xi Jinping to talk about what the White House called the “important progress” at meetings between the two countries in Beijing.

And while China’s foreign ministry issued a statement to clarify that the movement of the rig should not be seen as a retreat, Vietnam, at least, has proven its ability to insulate itself for the time being from low-order Chinese military intimidation and coercion – a move experts say other Southeast Asian countries will try to emulate.

“What they all want is to carve out a space where they can function and maintain their freedom of action and their presence in the South China Sea,” said Ott. “For the U.S., the question is, how far are we prepared to go in being a part of this game, and what is in it for the U.S.?”