China is not alone.

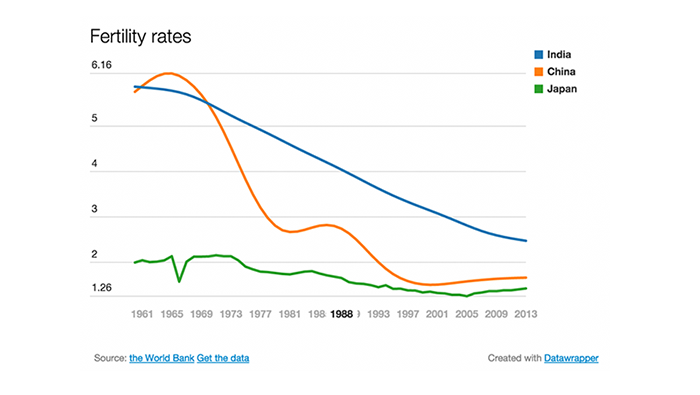

The Asian giant recently abandoned its one-child policy. But other Asian countries, seeking to maximize economic growth, are also struggling with population and family-size policies as they cope with lower fertility rates among their population.

However, demographers say socioeconomic changes – not government policies – are the fundamental reasons for low fertility rates and smaller families. Simply setting a population policy that encourages couples to reproduce won’t help much.

“It is not the government’s job to pay people or encourage people to have more children,” said Stuart Basten, associate professor of social policy at the University of Oxford. “But it is the government’s job to make society a better place and to help people in their aspirations to … achieve what they want to achieve. In that way, fertility rates would probably go up.”

Basten, in a telephone interview, noted that fertility rates in northern and Western Europe are relatively high, thanks to generous public assistance benefits.

In many countries, fertility rates are close to 2, which is the replacement level for developed countries. Replacement level ranges from 2.5 to 3.3 for developed countries due to higher mortality rates.

“We don’t have any policy which encourages people to have babies,” Basten said. “We have a lot of policy about childcare, maternity leave, [and a] national health system which supports older people… there is more a supportive atmosphere towards childbearing.”

More than three decades after the one-child policy, China’s working-age population has declined, and the “4-2-1” families – four grandparents, a married couple and their single child – put more burdens on young people growing into adulthood. In the vast country, urbanization brought many rural workers to cities over the past 30 years, and the excess of cheap labor eventually dried up as the cost of living rose. Similarly in Japan, after a decade of low fertility, the country is looking for more young workers and trying to attract more women to its labor force.

India, however, with a population rivaling China’s, has a different problem. The Indian government has been unable to bring down its fertility rate. The country simply doesn’t have enough jobs for its young people and has insufficient social care for its older population, which is also growing.

(In the United States, the fertility rate has stayed at about 2 since 1989, meaning on average women of childbearing age would have two children. However, rates have dropped a little since the financial crisis in 2008. The rate stood at 1.86 percent in 2013, according to Population Reference Bureau).

Demographers predict the change in China’s policy will not have a huge impact over the long run.

“The truth is that, before the relaxation of the one-child policy, there were substantial proportions of people [who] could and already had a second child, especially in the rural areas,” said Yong Cai, a sociology professor at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill.

The one-child policy exempted ethnic minorities, couples in some rural areas, and couples with a disabled first child. Some couples abused the latter exemption and provided fake medical documents to seek permission to have a second child.

The shrinking workforce and aging population are growing concerns for the Chinese government in Beijing. Two years ago, China relaxed the one-child policy by allowing families to have two children if either the husband or wife was an only child.

However, the relaxation of the 36-year-old policy did not create the baby boom projected by the government. By the end of last year, about one million couples applied to have a second child, compared to an expectation of 2 million, according to China’s National Health and Family Planning Commission.

“People are choosing not to have a second child obviously because of the policy, but more so because of socio-economic changes,” Cai explained. “Also, with almost 30 years of propaganda and brainwash, people start to accept the idea that one child is OK. You don’t need to go beyond two children.”

Jane Golley, an economist at Australian National University in Canberra, said relaxing the one-child policy was not a promising solution to the aging problem. “Because you need something to happen quicker than that,” she said, referring to the long period of time before babies grow to young adulthood and join the workforce.

“Even if it helps the aging problem, it creates a new youth dependency problem.” Golley said the government should instead invest in education and extend the retirement age to improve productivity.

China’s government listed delaying retirement age as an option in its 13th five-year plan published by Xinhua News this month. Currently, the retirement age is 60 for men, 50 for blue-collar women, and 55 for white-collar women.

The change in policy comes as China grapples with an economic slowdown that has triggered alarms across the world and is reminiscent Japan’s stagnation after its post-war economic miracle. However, Japan’s negative population growth and rapidly aging population made it harder for that country to recover from its stagnation in the 1990s.

Japan’s population grew at about one percent from the 1960s through the 1970s, but has declined sharply since then.

In 2005, Japan’s population declined for the first time since World War II, according to Japan’s Statistics Bureau. The 2010 census showed that 56.3 percent of the households were nuclear-families and 32.4 percent were one-person households.

“Aging and population decrease may reduce the productivity progress,” said Hisakazu Kato, an economics professor at Meiji University in Tokyo. “In addition, an aging society means that elderly persons often withdraw money from their account then the national savings rate and investment rate go down and the speed of capital accumulation decreases” he wrote in an email.

In Tokyo, the Japanese government has taken measures to encourage higher fertility rates. It allocated 24.4 billion yen ($198 million) for childcare services and the promotion of women’s participation in labor market. Another 3 billion yen ($24 million) in the 2013 fiscal budget went to programs designed to combat the declining birthrate. Local governments even arranged dating parties for young people to meet.

“The penalty or the cost of having children is extremely high. So having a little bit of government support is not really going to make much difference,” said Basten. Young Japanese have little job security, he said, work long hours and face high housing prices. Also, the traditional view still persists that married women should stay home and take care of their children

In Washington, John Seager, president of Population Connection, formerly known as Zero Population Growth, said allowing more immigration was a simple solution for Japan. “They can simply put up a help wanted sign in the direction of the Asian continent. And they would have absolutely no trouble attracting all the workers they could possibly want.”

In the past, the Japanese have not put out the welcome mat for immigrants. However, survey shows support for immigration is growing. However, immigration is not much welcomed in the homogeneous nation. A survey by a national Japanese newspaper Asahi Shimbun, in April showed that 51 percent of Japanese welcome foreigners who want to settle down permanently. A similar survey in 2010 showed that only 26 percent of Japanese showed support.

Hisakazu Kato projected that Japan could lose as much as one-third of its population in the next 50 years. “It will be necessary to accept around 30 million immigrants to compensate population decrease.”

Japan’s total population in 2014 was 127 million, compared to 1.35 billion in China.

While China and Japan are worrying about their aging population, India celebrates growth in its young workforce. The U.S. Census Bureau projected that India’s population would surpass China’s population in 2025.

India counted 1.29 billion residents last year but its population grows at about 3 times the rate in China, due to higher fertility rates.

However, fertility rates in India vary greatly by states. The central government has failed to meet its objectives of reducing the total fertility rate to the replacement level of 2.1 percent by the end of 2012. In its Twelfth Five Year Plan, the government listed measures such as raising the minimum age for marriage and granting more access to contraceptive services to help achieve the goal.

Moneer Alam, an economic demography professor at Institute of Economic Growth in India in New Delhi, projects that India will most likely achieve the replacement level by 2020. He cited high unmet needs for contraception, poor reproductive health care infrastructure and gender discrimination as challenges the Indian government faces.

Many women in India have little awareness or access to contraceptive methods, according to the Indian Express.

Alam said India faces a unique situation where both the young and old populations are growing. “Both are fraught with major policy implications…,” he said, “Unfortunately, India is facing problems at both the levels: jobless growth and no social protection for the elderly.”

Oxford’s Basten said that India will not suffer a shrinking workforce anytime soon. “Certain parts of India are aging rapidly but at the same time, there are still a lot of Indians [who] move around and migrate in lots of areas.”

Some states in India implemented a “two-child norm,” a China-type population policy that limits couple to two children and bars them from running for public office if they exceed the limit. According to the Hindu newspaper, the “two-child norm” was passed in 11 states.

But government alone cannot engineer the size of families. “In all parts of the world without this kind of strict policy, fertility has continued to decline,” Basten said.