WASHINGTON — As self-driving cars move toward becoming a reality for the general public, many blind or aging people and those with disabilities see a new opportunity for mobility approaching.

Advocates are pushing manufacturers and regulators to ensure that people with disabilities are included in the planning and development of automated technology and regulation.

“Our desire is to be in that same class of consumers with people who are already on the roads,” said Parnell Diggs, a board member at the National Federation of the Blind. “If there’s an autonomous car, there needs to be a means by which a blind person can operate that car as well.”

Kenneth Joh, a researcher at the Texas A&M Transportation Institute who also serves on the federal advisory Transportation Research Board, said that both people with disabilities and the manufacturers would benefit from including the disabled and elderly in the debate about the technology – and not just from some sense of social equity.

“It would behoove the auto industry – auto manufacturers – to certainly keep the elderly and the disabled in mind, as a growing proportion of the American population are aging baby boomers,” he said.

Already, there are worrisome signs that the technology will not be the boon for the disabled that it could be.

Last month, Chris Urmson, director of Google’s self-driving cars project, told the Senate Commerce, Science and Transportation Committee that Google is disappointed by California draft regulations released in December. The rules dealt with some levels of automation in cars but exclude fully self-driving cars, despite strong public support, especially among people with disabilities, Urmson said.

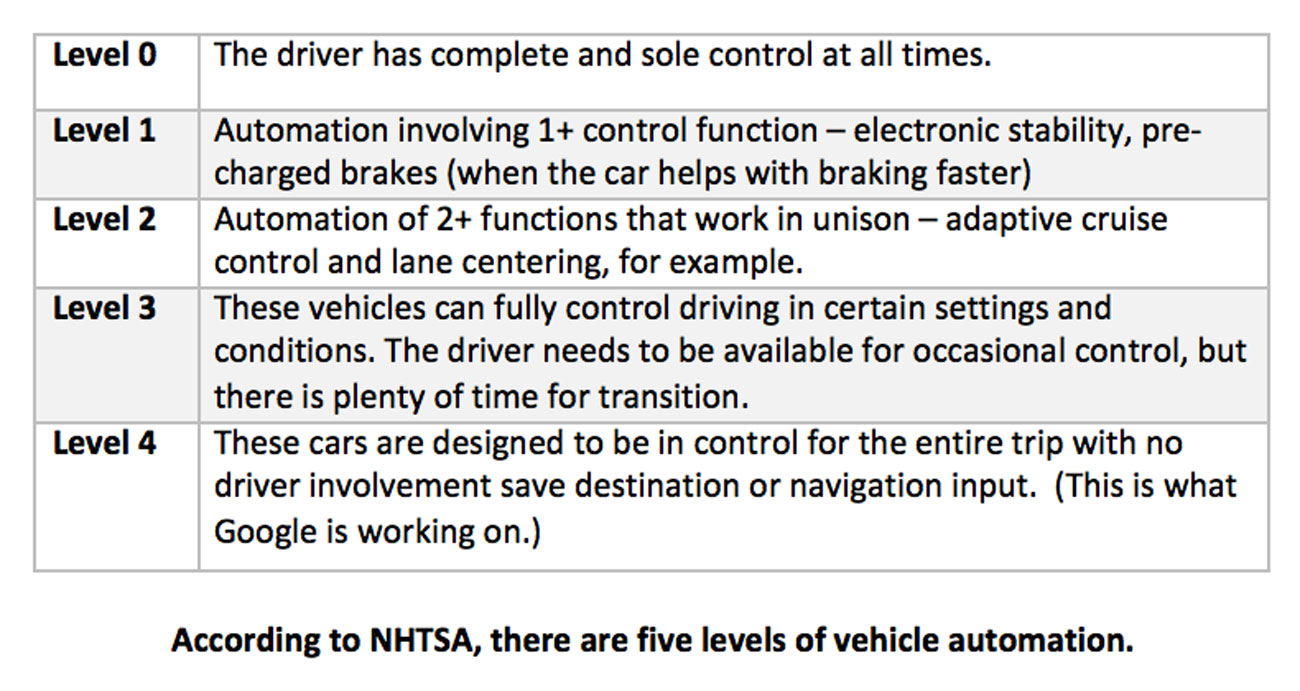

Varying degrees of automated technology already exist in cars for sale to the public, from automatic braking to lane correction, but fully automated vehicles still are operated only by test drivers.

According to the testimony before the Senate committee, Google has a fleet of 33 prototypes that require no human intervention and 23 modified SUVs. Each of Google’s self-driving prototypes has a removable steering wheel and pedals.

At an autonomous car conference in Detroit last month, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration chief Mark Rosekind said self-driving cars had potential social benefits:

“They promise new mobility options to those who have missed out on the benefits of a century of automotive history, including people with disabilities, elderly drivers and groups at an economic disadvantage.”

Diggs, who is blind, agrees and wants to make sure these communities’ needs are incorporated into original vehicle designs and not introduced later on or only as special retrofitted models.

In a way similar to how settings can be enabled on iPhones or computers to accommodate the blind, the technology can be built into the interface for autonomous vehicles, he said in a phone interview. Cars can be programmed to describe the field of vision to a blind driver and send warnings about tight turns or obstacles through vibrations and other triggers.

Diggs spoke, along with other interest groups and members of the public, at a daylong hearing on automated vehicles held by the highway safety administration – NHTSA – earlier this month in Washington. A second hearing is scheduled for April 27 at Stanford University.

There are many technological advances to discuss.

NVIDIA, a company based in Santa Clara, California, that designs graphics processing units, has developed a computer for self-driving cars that uses artificial intelligence to learn from new traffic situations and share that information with other cars using the same technology.

“We can handle the processing of different sensor inputs, and we can do all kinds of sensory outputs, whether it’s touch-based, whether it’s audible or visual,” said Danny Shapiro, senior director of NVIDIA’s Automotive Business Unit. “Our system that we’ve developed is not a fixed system. . . . It’s absolutely updateable, just like your phone is.”

Still, heightened expectations for self-driving cars are likely to be unrealistic at this point, cautioned Steven Shladover, one of the founders of the California PATH Program, a collaboration between government agencies and academic institutions to improve highway capacity, efficiency and safety through technology.

“This is where, unfortunately, the disabled community has been seriously misled by people into thinking that somehow they’re going to have automated vehicles driving them wherever they want to go in the near future,” he said. “That’s just not going to be feasible.”

When it comes to aging people and those with disabilities – even among those who once held driver’s licenses – each person’s impairment is different, and determining who can use which cars will present a “nightmare of complexity,” Shladover said.

NHTSA is crafting federal guidelines for automated vehicles that are expected to include recognition of the needs of blind people and those with other disabilities. Many at the Washington hearing voiced safety concerns, pointing to crash and malfunction reports from trial runs.

“People disagree about how fast it might happen, but I think that technology has proven that it will happen one day,” said Diggs, the advocate for the blind. “When that time comes that there actually are cars on the road that are reliably capable of navigating without any intervention from the driver, we intend to be part of that group.”