WASHINGTON — Kicking a red ball fiercely across the laboratory floor like a professional soccer player, Darwin-OP2, a human-like robot, says in a monotone voice that he is excited to “be friends and play soccer.”

Darwin-OP2 isn’t a toy, but one of the most advanced examples of research and development into what is known as assisted robotics and humanoid interaction. He has been programmed by Chung Hyuk Park, an assistant professor of biomedical engineering at George Washington University, to help children with autism to be more engaged with society.

“The ultimate goal would be to utilize a robotic system to help the children with autism in communicating with others more easily and feeling more comfortable in daily living,” Park said.

Park’s project, which is in its early stages, focuses on how the robots can help children from five to 10 years old, but may soon include children as young as three, he says. Ultimately, he hopes to make the technology affordable for all families with children with autism.

Autism is a spectrum disorder. It varies case by case, but one common trait is that children avoid eye contact, which makes it difficult for to them to interact with playmates, family members and others.

Park said research has shown that children with autism are more comfortable interacting with robots because they can control their actions, making them more predictable than human playmates.

“Children with autism have trouble understanding and engaging other people’s emotions, and with socially assistive robots, the child may be more readily engaged without being overwhelmed,” agrees Laurie Dickstein-Fischer, an assistant professor at Massachusetts’ Salem State University’s School of Education who is also doing clinical research on how to use robots to help children with autism.

The robots use artificial intelligence, which analyzes the children’s behavior and uses that data to adapt to how it engages with them.

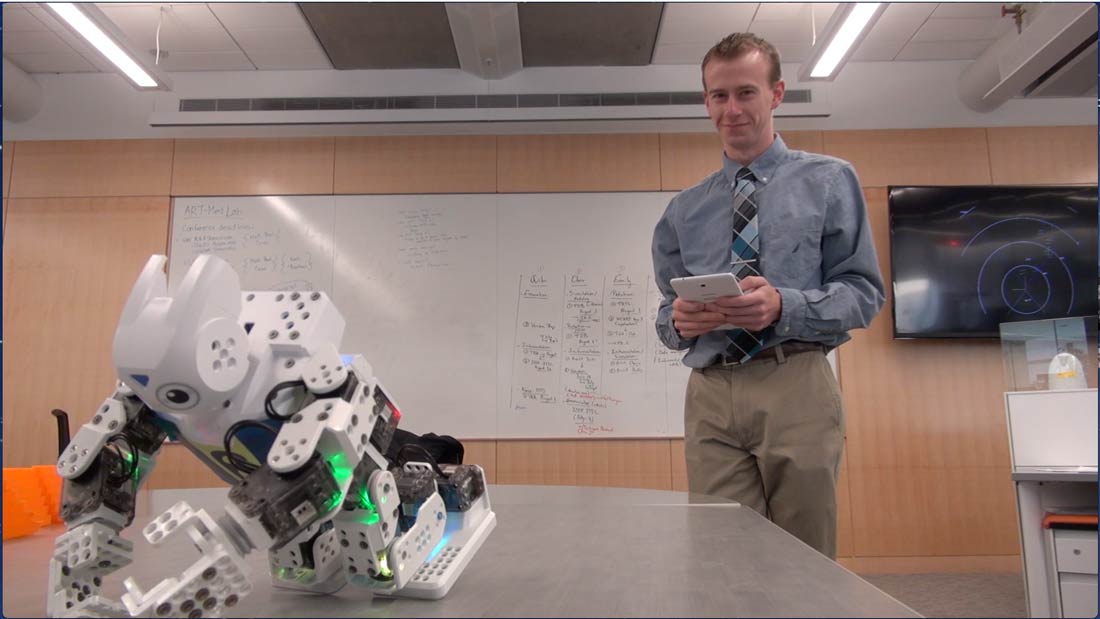

Park is experimenting with three different models of robots. One is a mini robot that’s connected to an iPhone to display facial emotions, another is a medium robot that can do diverse dance movements and gestures in response to social cues.

And then there is Darwin-OP2, a larger and more sophisticated robot that interacts with children by playing soccer and performing other activities.

“Based on the music, the robot is doing dances, and you are hoping the child can also dance along,” said Park.

Experts also say teaching social skills to children with autism requires frequent repetition, another perfect task for robots. And Dickstein-Fischer said robots can help parents with applied behavior analysis therapy, which requires intensive hours spent with a child. It can be a “supplement for those who can’t get that 40 hours per week,” she said.

Moreover, robots can collect data that provides useful analysis to parents, helping them understand their child’s behavior.

Yetta Myrick, the mother of a 12-year-old son diagnosed with autism, says the possibilities are intriguing.

Although she hasn’t met Darwin-OP2, Myrick said her son Aidan would like him, because he is less confusing and intimidating than human playmates. Myrick said, however, that the robots should be used as a complement to existing treatment. “We as parents have to be involved with the children!” stressed Myrick, the executive director and president of DC Autism Parents.

Park is looking to test his research schools, childhood development centers and other institutions dealing with autism. Once his research is well underway, he hopes to prove that music and social behaviors can stimulate children with autism to improve their conditions.

The professor, who was born in Korea, said the robots have a long way to go, both in terms of controlling their movements and improving on artificial intelligence. “Making them work, being more human like, is still our dream,” Park said.

Darwin-OP2 seemed to agree. “Be my coach to improve my behavior,” he said.