WASHINGTON – Holocaust survivor Nat Shaffir always looks forward to the somber Reading of Names ceremony in the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum’s Hall of Remembrance. “Out of 33 members of my family, 32 were murdered, and today was one of the times I can actually read their names out loud so people can listen,” he said.

Each year, the Holocaust Museum holds a reading of the names of more than 5,000 people confirmed to have died in the Holocaust – documented names known to the institution. Relatives and members of various communities are invited to volunteer as readers or recognize the names of loved ones. The point is to remember all of the individuals who comprise the enormous group killed during the Holocaust – some 6 million Jews — and to try to prevent another genocide.

Nat Shaffir, an 80-year-old Holocaust survivor who now volunteers at the Holocaust Museum. (Nick Zazulia/MNS)

Shaffir, a tour guide who has been volunteering at the museum for nearly seven years, was one of the readers Monday. He has participated in readings both here and in Israel. Seventy-one years after the end of World War II, there aren’t many survivors left.

“At 80 years old, I’m one of the younger survivors. The 90-year-olds are dying out,” Shaffir said. “There’s nobody to tell our story later on, and we appreciate that younger generation that comes and listens to what we have to say who will continue and be our witnesses, our information for further generations to tell the story of what happened here.

Jordan Allen, 36, a visitor services coordinator at the museum, has been participating in the name readings since he started working there 14 years ago. The meaning of the event, for him, has evolved over the years.

“Working here, I became very close with some Holocaust survivors, and some have perished,” Allen said. “So when I’m reading names, I’m also thinking of them and their lives, and how their family members have survived and died, and being able to hear their stories.”

As names were recited, visitors trickled in and out of the austere atrium of the Hall of Remembrance, listening and taking up small sticks to light candles set in two rows around the edges of the room’s six sides. The little flames flickered under the names of locations where people were taken to be killed by the Nazis during the Holocaust. Under one such name, Treblinka, Leon Tsymberov helped his son kindle a light.

“I grew up with this,” said Tsymberov, 51, who was visiting from Boston but is originally from St. Petersburg, Russia. “I’ve heard a lot of stories in the family. Part of my family died in the Holocaust; part of my family died fighting in the war.

“It’s very sad to see the name of the place that my grandparents are from on the wall,” Tsymberov said, referring to the raised, black letters on the museum’s wall showing locations where the Nazis took their victims. He also said that the location “pretty much disappeared in the Holocaust. The place that is part of the Jewish language is gone… People have returned there, but it’s not what it used to be anymore.”

Tsymberov, who first visited the Holocaust Museum years ago, believes that the reminders are important to prevent history from repeating itself. That’s why he brought his young son.

“Kids have to know about this no matter how difficult it is, how tearful it is,” he said. “They have to know because they have to pass it along. That’s the only way for it not to happen again. They need to see it with their own eyes and hear the story. It needs to be passed on from parents to children.”

The war in Europe ended with Germany’s surrender on May 8, 1945, liberating survivors from the death camps.

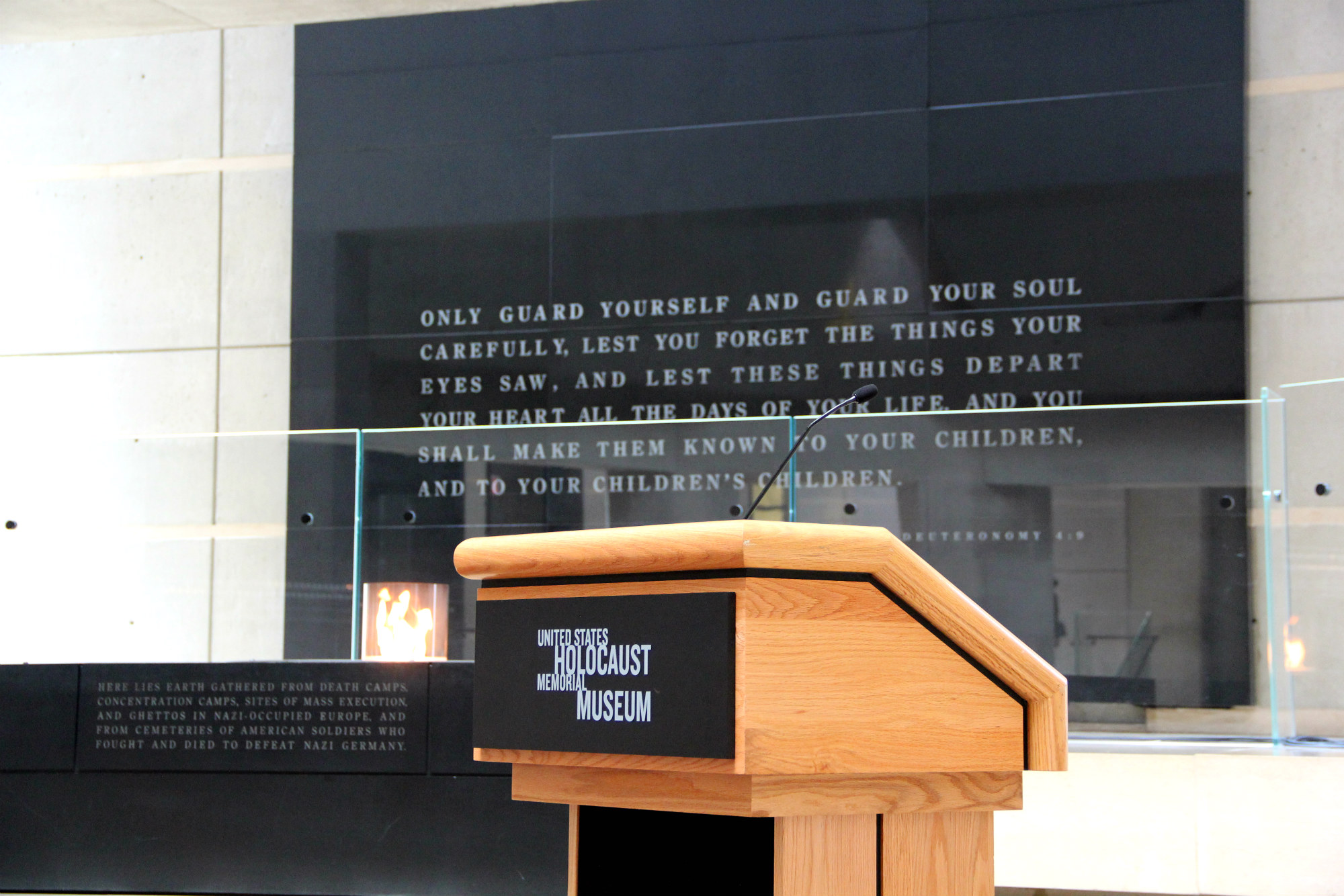

A wall in the Holocaust Museum’s Hall of Remembrance. The Treblinka extermination camp in Poland was the site of more Jews’ deaths than any other camp except Auschwitz. (Nick Zazulia/MNS)