WASHINGTON –While the Pentagon has dropped its ban on transgender troops, the world of science is struggling to improve the history of harassment against transgender physicists and other scientists.

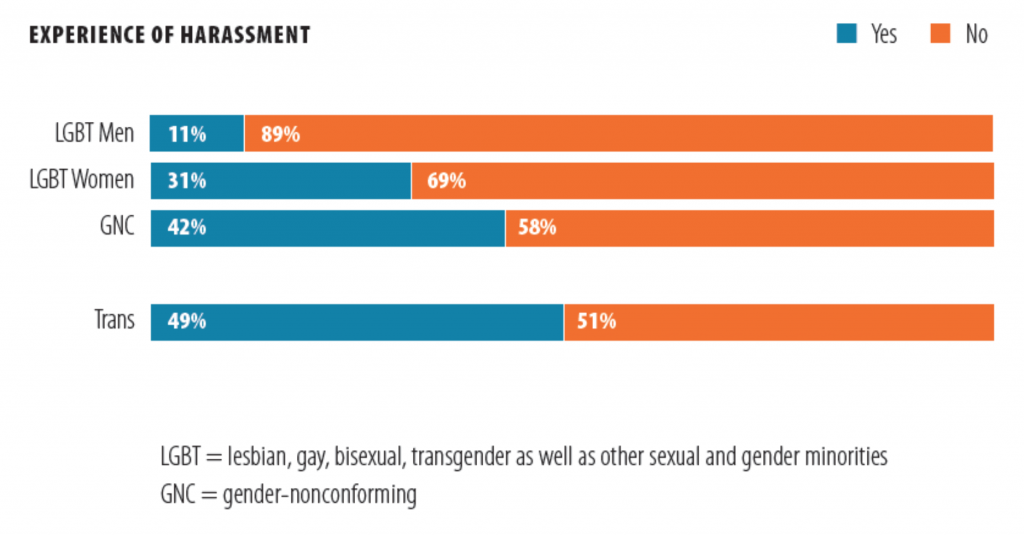

According to a recent study by the American Physical Society and the American Association for the Advancement of Science, transgender physicists experience some of the highest rates of harassment of LGBTQ scientists: one in two transgender people are harassed at university and research settings.

As a result, about 36 percent of transgender physicists consider a career change and many of their lesbian, gay, and bisexual peers avoid specializations in physics out of fear of harassment.

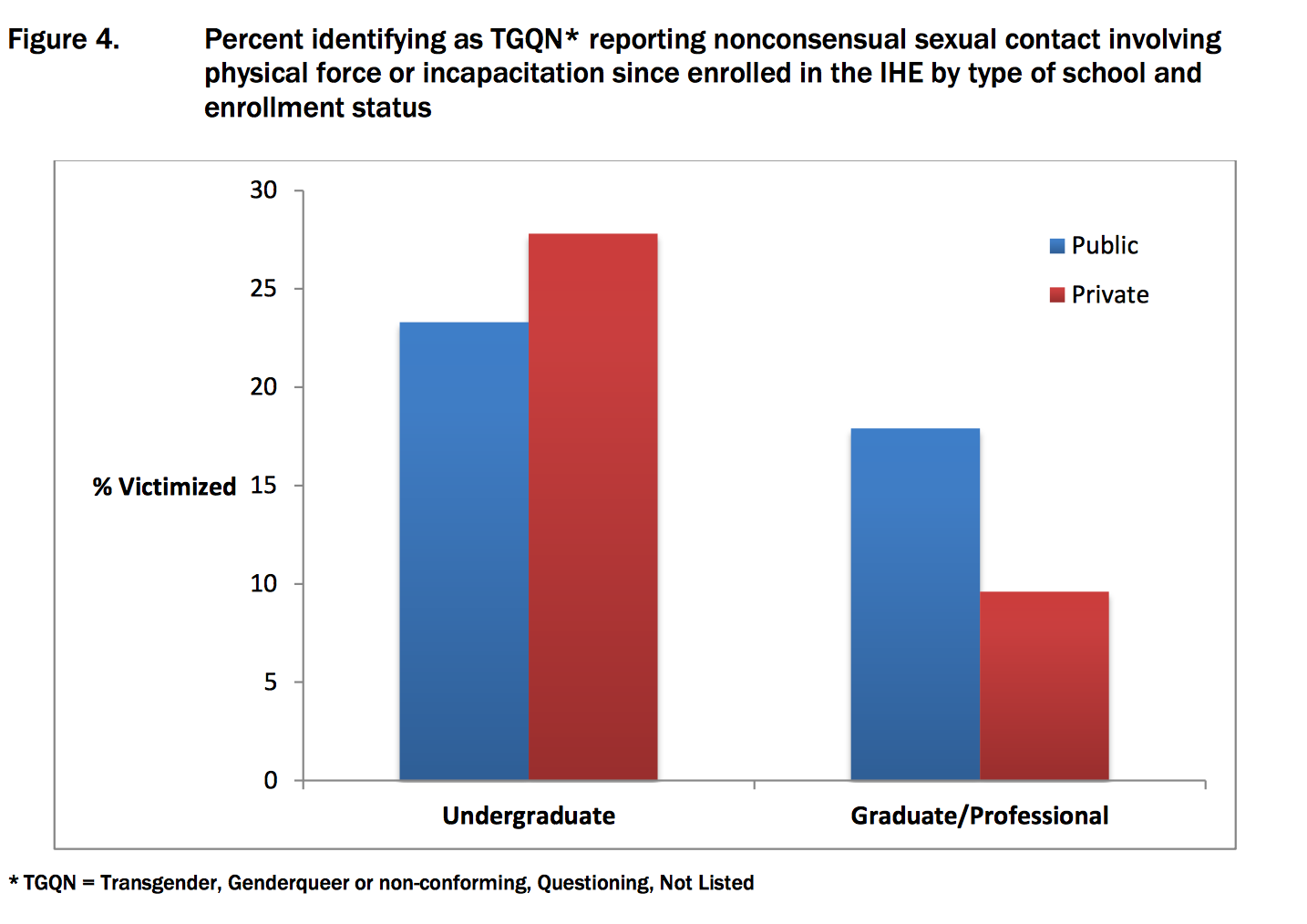

This corresponds with a larger survey of harassment, specifically sexual harassment on university campuses by the American Association of Universities.

The AAU report called the AAU Climate Survey on Sexual Assault and Sexual Misconduct found that both undergraduate and graduate students who were TGQN or transgender, gender queer, non-conforming, or questioning, had the highest risk for sexual assault or misconduct.

According to a survey conducted by the AAU, undergraduate TGQN students experienced more harassment than TGQN graduate students.

TGQN, for example, had the highest rate of “the most serious form of sexual assault,” rape, on campuses with, “undergraduates (12.4%), followed by undergraduate females (10.8%), and TGQN graduate/professional students (8.3%).”

Transgender scientists experience some of the highest levels of harassment of all LGBTQ scientists. Courtesy of LGBT Climate in Physics, American Physical Society.

Along with harassment, many LGBTQ physicists are ostracized for their gender expression, making it harder to conduct collaborative research, find mentors and network with peers, the survey found.

“I think the first issue to raise is that there is an issue within the physics community. We tend to think everything is based on the science and nothing else matters. There is a culture behind that-there are less women, less people of color, and then statistics show a number of issues for LGBTQ people in the field,” said Dr. Elena Long a transgender physicist and co-author of the study.

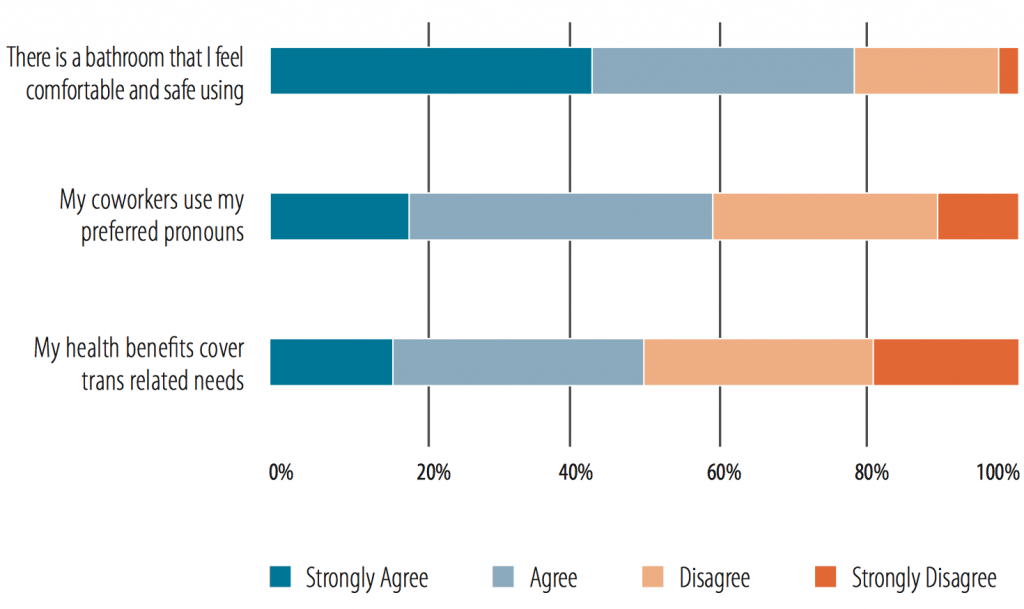

She said in her own experience transgender scientists are called by incorrect gender pronouns and are not able to formally change their names in scientific publications.

Different forms of harassment that transgender scientists experience. Photo courtesy of LGBT Climate in Physics, American Physical Society.

Dr. Ramon Barthelemy, a co-author of the study and a LGBTQ physicist, said not being able to change a professional publication record is especially problematic in the sciences.

“Trans physicists can either out themselves as trans or remove half of their publications. Either way, they have to potentially face discrimination or make themselves look less accomplished during the job search,” said Barthelemy, one of the researchers who conducted the survey.

In order to address the harassment faced by LGBTQ physicists, especially those who are transgender, the APS adopted six policy recommendations including the creation of the Forum.

But Dr. Van Dixon astronomer at the Space Science Telescope and head of the AAS Committee for Sexual-Orientation & Gender Minorities in Astronomy, said this harassment doesn’t stop with LGBTQ people. He thinks people of color and women in the sciences experience harassment as well.

“The challenges faced by people with “additional marginalized identities” and the hostile environments in which transgender and gender-nonconforming people often find themselves,” said Dixon. “We speak of ‘intersectionality,’ people at the intersection of two minority groups (lesbians of color, for example) who face discrimination not only from the majority culture, but from within their minority communities.”

Barthelemy said he interviewed an African American, female, lesbian scientist for the study who said she had experienced so much harassment in the sciences as an LGBTQ person and minority, she was considering a career change.

“She said she simply couldn’t handle being a woman, a person of color and a lesbian in this community anymore,” he said.

That’s why the American Society for Cell Biology and the American Astronomical Society, have created committees that not only address the experience of LGBTQ scientists, but people of color and women.

Dr. Bruno da Rocha Azevedo, lab director and research scientist at UT Southwestern Medical Center, heads the LGBTQ Diversity Committee of the American Society for Cell Biology. He said his committee has sponsored LGBTQ seminars, mentoring and networking events at annual meetings as travel to NOGLSTOP conferences.

“My experience hearing stories from multiple people tells me that trans people have a harder time [when it comes] to being openly LGBTQ, and some people think that ‘being gay doesn’t change anything regarding his/her science’, an approach I personally disagree with,” said da Rocha Azevedo.

Dixon, a researcher at the Space Telescope Science Institute and chair of the American Astronomical Society’s Committee for Sexual-Orientation and Gender Minorities in Astronomy, said physics is one of the most challenging fields for LGBTQ people to enter. He said his committee has sponsored informational workshops on LGBT issues and LGBTQ recruiting events at undergraduate programs.

Berthelemy said that the survey helped push people in the sciences to try to change things.

“It’s the campfire rule,” said he. “You want to leave the site better than when you entered it.”