WASHINGTON — Farmers are waging war against a weed commonly known as pigweed, but their best weapon is a controversial herbicide that can damage other crops.

Called amaranth by chemical companies developing herbicides to fight it, pigweed is a leafy green plant that can grow up to six feet tall. It is invading soybean fields throughout the southern United States, says American Farm Bureau Federation Communications Officer Andrew Walmsley.

Pigweed can grow to be six feet tall. Photo courtesy of State of Maine government website.

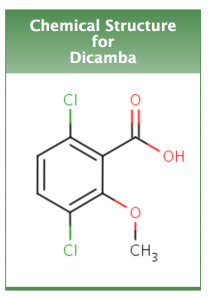

Unfortunately, Walmsley says, the weapons used against the weed are either costly, such as hand-harvesting it – bend over and pull the stuff out — or illegal, like spraying soybean crops with dicamba, a herbicide that is a derivative of benzoic acid. The herbicide isn’t harmful to humans or animals, but is deadly to plants that don’t have a resistance to it.

According to an Environmental Protection Agency compliance advisory released earlier this month, there have been over 117 complaints filed with the Missouri Department of Agriculture about dicamba. In Missouri, for example, more than 42,000 acres of crops were reportedly destroyed by the herbicide, according to EPA.

And it’s not just soybean and corn crops that are being affected, but also peach and cotton crops, all staples of farming economies in Alabama, Arkansas, Kentucky, Mississippi, North Carolina, Tennessee and Texas, and also Missouri, Illinois and Minnesota.

Soybean plants. Photo courtesy of USDA.

Dicamba isn’t a new herbicide, says Jerry Green of Green Ways Consulting LLC, a Pennsylvania company that consults with farmers on pest control. It’s been on the market for more than half a century, yet spraying it on soybean crops is a new application, and if sprayed during growing season, illegal.

The EPA has not registered the use of dicamba as an herbicide for application on growing soybean or cotton plants – that is, during the growing season when its weed-killing capabilities would be optimized. Under the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA), the EPA can “assess civil and criminal penalties” when a herbicide like dicamba is used without authorization, or used improperly.

Chemical structure of Dicamba. Photo courtesy of the EPA.

Green says many farmers’ best bet for fighting pigweed may be in the form of genetically modified soybean crops. These crops have an added genetic trait of dicamba resistance which allows them to be sprayed with the herbicide, with little to no side effects. This would allow farmers to spray their fields with dicamba to wipe out most of the pigweed, but save the soybean crop.

But that doesn’t solve another problem. dicamba has what’s called a high drift factor which makes it easy for the herbicide to be carried to other crops in neighboring fields, killing crops that don’t have the special dicamba resistant trait.

Until the EPA approves a broader range of use for dicamba, or until the manufacturer, Monsanto, develops a more farm-friendly herbicide, most farmers may feel like they’re losing the battle, the Farm Bureau’s Walmsley said.

He said St. Louis-based Monsanto has been sending out experts to train farmers how to better use dicamba, from new nozzle regulations and better spraying techniques to recommendations on ideal weather conditions for spraying.

But the Farm Bureau official said this does little to help farmers who want to use dicamba in urban settings or other dense population areas where it could easily kill fruits or vegetables in a garden.

Miriam Paris, U.S. soybean marketing manager for Monsanto, said in a recent blog post that the company hopes to be able to legally sell dicamba to farmers next season. In the meantime Monsanto does “condone the illegal use of any pesticide for any purpose.”

“Reports alleging that some applicators are illegally using dicamba are a concern. However, it is our experience that the overwhelming majority of farmers comply with the law and follow best stewardship practices,” said Paris. “We are confident that state officials will evaluate the situation and take appropriate action.”

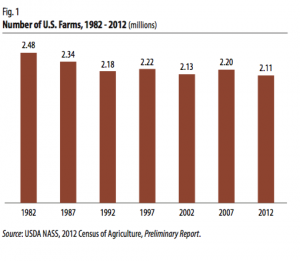

Herbicides are still critical tools on most farms. Micheal Owen, an agricultural sciences professor at Iowa State University, said the days when farmers comprised some 30 percent of the U.S. population and hand-harvesting was common are long gone. Quite simply, he said with only about five percent of the population farming the land, growers need help controlling weeds that choke off their cash crops.

Number of farms. Photo courtesy of the USDA.

Yet Owen too is concerned with the choice of dicamba, as its use is against EPA regulations and could put nearby crops at risk.

In Knoxville, University of Tennessee plant science professor Tom Mueller warns that farmers must diversify their attacks on harmful weeds or see resistance grow among the sturdy invaders against stronger herbicides, including dicamba.

He likened it to antibiotic resistance: if only one antibiotic or one method is used to fight a bacterial infection, eventually it will build up resistance to it.

It’s similar in farming.

“Ten years ago, the glyphosate molecule was the dominant weed control in broad acre agriculture. If you look back …there were very simple systems that we have resistance to. The systems in the future will be more complex and I would imagine dicamba and other molecules would be in a more complex system,” said Mueller.