WASHINGTON–Arden Tewksbury has been a dairy farmer in northeast Pennsylvania for most of his 83 years. He’s also an agricultural activist who is part of a movement to try to stop the loss of family-owned dairy farms across the country due to record-low milk prices, a glut of milk on the world and U.S. markets and reduced federal subsidies.

According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the price of milk in June was about $15 per 100 pounds, or cwt — more than a 40 percent drop from 2014 milk prices. Meanwhile, the USDA estimated milk production costs were about $22 dollars per cwt.

Former Commissioner of the New York State Department of Agriculture and Markets Darrel Aubertine said many small family farms now face a difficult decision: sell the family dairy farm to larger dairy farms, borrow money from banks, or diversify their operations into other types of agriculture, such as growing crops.

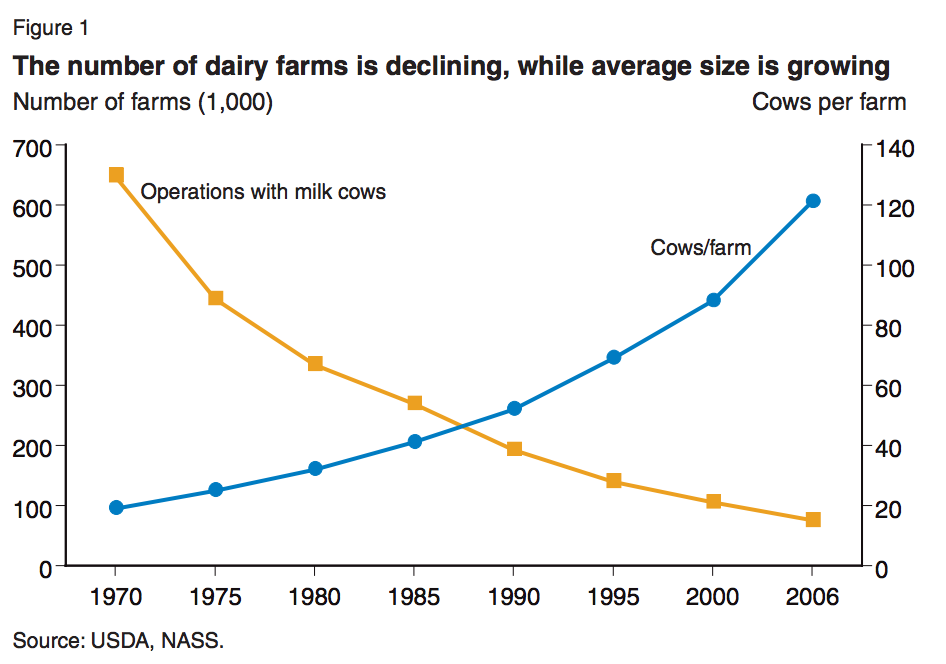

According to a USDA report, the number of family dairy farms decreased from 648,000 in 1970 to 75,000 farms in 2006 as milk production increased twelvefold.

The number of small, family dairy farms are decreasing in the U.S. Chart courtesy of the USDA.

Tewksbury put part of the blame for the stark choices facing today’s dairy farmers on the Federal Agriculture and Improvement Act of 1996, which allowed the USA to set the price of milk using a formula that Tewksbury said doesn’t take into account the cost of dairy production.

He also blamed the law for cutting federal assistance available to dairy farmers from the Commodity Credit Corporation, which provides loans and buybacks of surplus milk.

About 60 members of Congress from dairy states have taken up the cause of the small dairy farmers, sending a letter to Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack in June pointing out what they called the “troubling economic challenges facing U.S. dairy farmers and the entire U.S. dairy industry” due to low milk prices. They urged Vilsack to make “an immediate market financial injection and offer financial assistance that will directly support U.S. dairy farmers equally” under the CCC Charter Act.

The letter suggested many factors that contributed to the record low in milk prices — from a surplus in milk in the American and global dairy markets to the 2014 Farm Bill, which replaced the Milk Income Loss Contract payments with the less effective Dairy Margin Protection program that required dairy farmers to buy into the program before they could receive any assistance.

And the USDA’s “Dairy: World Markets and Trade Report” agrees with the list of these drivers of low milk prices in the U.S.

“It is apparent that low milk prices and corresponding low margins are taking a toll on dairy farmers worldwide,” the report said.

The report said that even though the price of milk powder has increased and may be the first sign that the world surplus of milk driving prices down globally is self-correcting itself, “any significant recovery appears unlikely until well into 2017.”

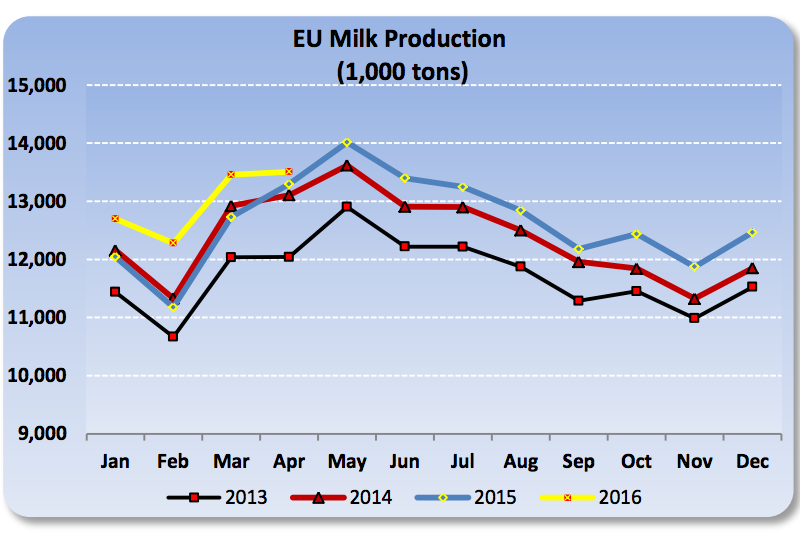

In the meantime, the report said milk production in the EU is actually predicted to decrease for the rest of 2016 but with increased farmer assistance in EU countries, production should still remain at a steady 1 percent increase, or over 150 million pounds of milk produced in 2016: quite a global surplus indeed.

EU prices will continue to increase by one percent according to the USDA. Chart courtesy of the USDA.

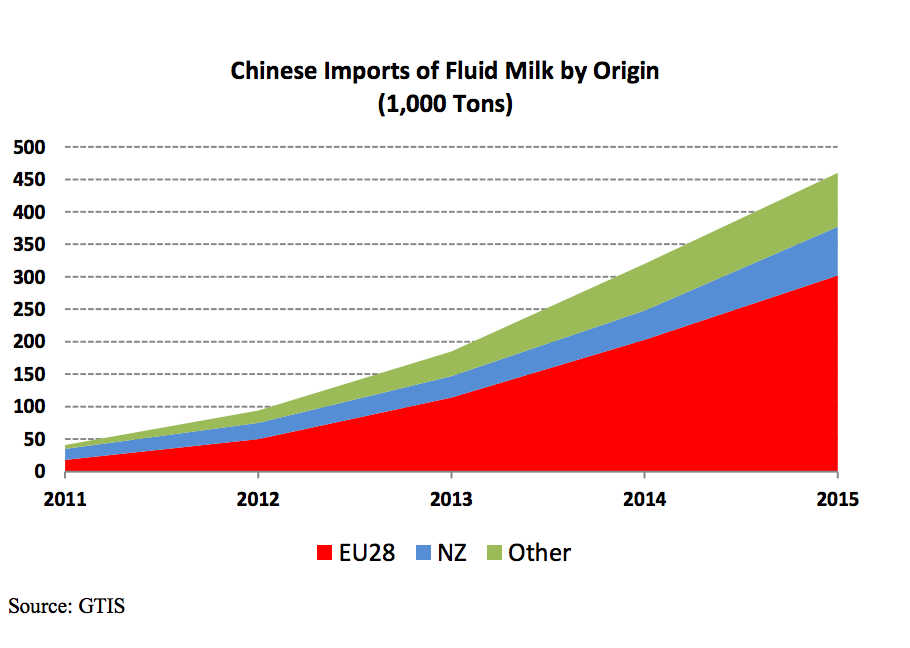

The USDA report also predicted China might import some of this global milk surplus, as the country imports almost two thirds of its milk from the EU, but another crucial milk import market in Russia won’t be importing any foreign milk until Dec. 31, 2017.

China might import a significant amount of the global milk surplus. Chart courtesy of the USDA.

There still hasn’t been a response from Tom Vilsack or the USDA to the letter, but the National Farmers Union sent a follow-up letter on August 8, 2016 asking the USDA to buy between $100m to $150m worth of milk products to reduce the milk surplus.

Cindy Gallagher a 54-year-old sixth generation dairy farmer from Waterville, New York said she and her husband relied on selling timber and his part-time law business to make ends meet last year.

“Where we live nobody is even breaking even. Everyone’s losing a lot per cow and the stress is huge,” Gallagher said. “They’re getting to the point where people are at the end of the availability of credit.”

Dylan Hapeman, a 20 year-old dairy farmer in Little Falls, New York said even though his cost of production is about $18 to $20 per cwt, he’s only making about $13 per cwt, well below the national average but still can’t get federal aid to offset the deficit. Like the Gallaghers, he and his fiancée rely on her job to support the farm.

Seth Squires, an 18-year-old dairy farmer in Munnsville, New York said that a milk processor stopped picking up at 19 small, family dairy farms things got so bad this year. One of his friends already has been dropped from Elmhurst dairy. And now, he’s worried about the future of his family’s own second generation dairy farm.

Like Squires, Gretchen Maine, a 68-year-old dairy farmer in Waterville, New York, said this year may be the last for her family’s third-generation dairy farm because they have already sold most of their cows to cover costs.

“We were third generation and we’re the end,” she said.

Milk can still be produced by larger, corporate-owned dairies that can absorb market dips more easily, but Hapeman said the family dairy farms support their local communities more than corporate dairies.

He explained it this way: If a machine breaks on a corporate dairy, the owners have their own carpenters and welders. But as a small farm owner, he goes to his local hardware and auto stores to buy parts. Without this business, he said local mom and pop shops and economies in small towns would suffer.

Tewksbury said Elmhurst Dairy, opened by brothers Max and Arthur Schwartz in 1919 in Queens, New York, will close on Oct. 1. The processing plant has supplied New Yorkers with milk for almost 100 years, but because of low milk prices, thousands of workers will lose their jobs.

When Congress reconvenes in September, farmers, activists and academics will be ready with a list of solutions to save the small dairy farms.

Gallagher, the Waterville, New York, farmer said the government should buy more surplus milk and cheese and donate it to food banks through programs like the Emergency Food Assistance Program.

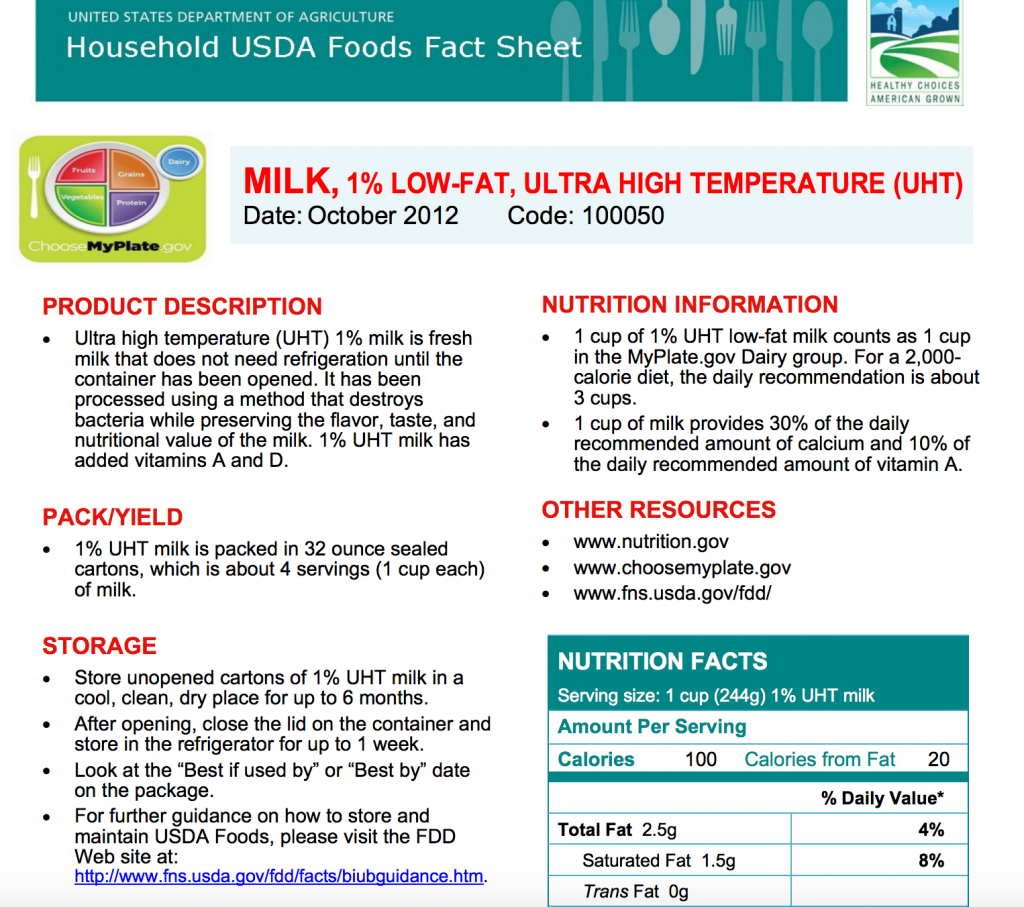

Low-fat milk fact sheet from TEFAP. Much of the milk that provides low income families with nutrition is surplus milk bought by the government. Photo courtesy of USDA.

Tewksbury and other said Congress should put a milk management program in place, similar to one in Canada,that would set production quotas for dairy farmers. Sen. Robert Casey, D-Pa., has proposed legislation to ensure that all farms, especially corporate diary farms, don’t flood the market with surplus milk.

And Cornell University agricultural economics professor Andrew Novakovic suggests farm savings accounts that would allow farmers to invest their money, at a high interest rate, tax-free.

In the meantime, dairy farmers like Seth Squires don’t know what they’ll do to keep their farms going without either federal help or a spike in milk prices.

“I really have no idea, that’s the scary part,” said Squires. “This is my life. This is what I’ve done.”