BLOOMINGTON, Ill. – Conserving the diminutive monarch butterfly is a giant issue for Illinois farmers, agriculture experts and conservationists, as its listing as “threatened” looms while the number of acres devoted to butterfly habitat balloons to 87,000 statewide.

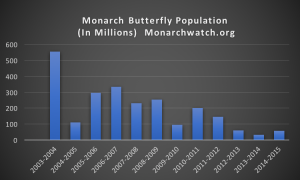

Monarch butterflies today number about 34 million, the U.S. Department of Agriculture estimates—a 90 percent decline over the past 20 years. The federal government’s goal is to get the population back to a robust 250 million by 2020, and the number of milkweed plants, which are vital to the life cycle of the monarchs, to 300 million, according to Abigail Derby Lewis, senior conservation ecologist, Chicago region at the Field Museum.

The milkweed plant is absent from much of the 3,000-mile migratory route from Mexico to Canada, east of the Rocky Mountains. Millions of acres of farmland in 10 states, including Illinois, line this route, USDA data shows.

The monarch may hit U.S. Fish and Wildlife’s threatened species list as early as 2019, and in order to prepare for that possibility, many Illinois farmers have been proactive about conservation, devoting a portion of their land to the milkweed plant and other favorable pollinator flora in exchange for a federal subsidy. This acts as a kind of get-out-of-jail-free card for farmers, Kankakee farmer and Soil and Water Conservation District Board Member Jeff O’Connor said, because much uncertainty exists about how monarch habitat loss would be restored and whether any restrictions could be imposed on farmers’ practices on their private lands. All parties are working together to try to prevent a listing from happening.

The USDA, through its Conservation Reserve Program, is subsidizing farmers in the 10 states between $100 and $300 per acre to plant milkweed and other favorable plants for pollinators like the monarch, O’Connor noted. Meanwhile, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is charged with enforcement of regulations imposed by former President Barack Obama’s 2014 National Strategy to Promote the Health of Honey Bees and Other Pollinators and the Endangered Species Act of 1973.

Both the Obama directive and the Endangered Species Act seek to arrest the decline of key pollinator species by providing incentives to solve the problem.

Farmers in Illinois are doing their part to plant pollinator habitat.

Iroquois County, about 75 miles south of Chicago, is at the epicenter of Illinois farmer enrollment in the pollinator program. The CP-42 program, as it is known, is administered by the USDA’s Farm Services Agency, with technical assistance from its Natural Resources Conservation Services arm, said John Englert, NRCS national program leader for plant materials.

“As of 2016, Iroquois County has had 5,000 acres registered in the CP-42 program — the program began in earnest in 2014, and has proliferated in 2016 and 2017,” Iroquois NRCS director Thad Eshleman said.

As the global glut of corn and soybeans is keeping prices and yields low, the CP-42 program helps farmers find yield on lands that would never normally produce and thus allows them to maintain a small return, Eshleman said.

“Some farmers in Iroquois County have planted as many as 80 acres of pollinator habitat as part of the program,” Eshleman said. He noted that the county’s often arid and sandy soil can make it difficult to grow other crops.

The goal of monarch conservation has attracted a variety of stakeholders. Nobody knows that better than Iris Caldwell, biological research engineer at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Caldwell chairs a diverse, 100-person working group on the subject that meets semiannually to discuss the matter.

“This group is comprised of agriculture advocates, including large companies like Monsanto and groups like the Illinois Corn Growers Association as well as rights-of-way organizations like the Illinois Department of Transportation,” Caldwell said.

The issue is producing some nontraditional bedfellows: German pesticide giant BASF and American agrichemical giant Monsanto are partnering with conservationists to protect the monarch through the Living Acres Monarch Challenge program and the Monarch Collaborative.

BASF’s Living Acres Monarch Challenge gives farmers resources and education to understand how to grow milkweed alongside their cash crops, BASF Functional Crop Care Scientist Laura Ivy Vance said.

“In terms of The Monarch Collaborative, a national organization comprised of farmers, agribusiness, conservation groups and universities, Monsanto has kicked in $3.6 million and the project overall has had a $20 million impact that funded the planting of over 200,000 milkweed plants,” Monsanto’s Eric Sachs said.

Illinois has an impressive amount of farmland devoted to its USDA CP-42 pollinator habitat program, making it second among the 10 states in acres set aside, according to Illinois Farm Bureau Director of Natural and Environmental Resources Lyndsey Ramsey.

But four major cities are also getting involved in habitat restoration, which could be a game-changer in the quest to keep the monarch off the threatened species list, said Derby Lewis, the Field Museum ecologist.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Field Museum administer the Urban Monarch Conservation Program which uses geospatial software to map the areas in Chicago, Minneapolis-St. Paul, Kansas City and Austin, Texas, where monarch habitat is growing and where it could have the greatest likelihood of growing, Derby Lewis said.

Cities along the monarch migration route collectively occupy almost 1.5 million acres, according to Derby Lewis, and if the project can get 5 to 10 percent of their population planting milkweed, monarch habitat loss may become a thing of the past.

The Field Museum is particularly focused on so-called collar counties, where large corporate headquarters’ land has a great potential for the development of habitat proliferation.

The monarch is an iconic species – with its distinctive orange and black wings, it travels from Central America to Canada every year, and is celebrated in the works of Barbara Kingsolver and Hector Duarte, according to the Chicago Zoological Society’s Andre Copeland.

“It is not only the utilitarian value of the butterfly that stands out most—the potential of the butterfly to influence the protection of foraging areas for the venerable bumblebee— it is the aesthetic and cultural value that’s most important,” he said.

In 2014, a petition was filed with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service asking that the species be listed as “threatened.” Two key environmental organizations were the lead petitioners: The Center for Food Safety, and The Center for Biological Diversity.

“We are … at the forefront at looking at trends in agricultural biotechnology and its effects,” Center for Food Safety Science policy Analyst Bill Freese said. “Right now, scientists estimate that 99 percent of the monarch’s pollinator habitat is lost.”

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service now must complete the review process to determine if the “threatened” status is warranted, which takes about two years. If a listing is recommended, it must be posted in the Federal Register, which likely would occur in 2020. Then state management plans, which already are underway in some states, would have to be created and implemented, Illinois Farm Bureau Director of Natural and Environmental Resources Lyndsey Ramsey said.

None of the interested parties – from environmentalists to agribusiness – want the monarch to be listed as “threatened,” U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service spokeswoman Mara Koenig said. Instead, as they work together to avoid the listing through conservation efforts that would increase the number of monarchs, they also have turned the age-old opposition between agriculture and the environment on its head.