Shark Week 2017 has come to a close, but that doesn’t mean the shark conversation should end. We can let the CGI one that raced Michael Phelps go until next year, but the 500-plus species currently living in our oceans need us to keep the discussion about shark conservation going.

Humans have talked about shark attacks since the days of Ancient Greece—the historian Herodotus (485-425 BC) described a battle at sea where many sailors ended up as shark food when the boats sank. But every year, humans kill over 200 million sharks, sometimes by accident, when they get stuck in nets, and sometimes intentionally, when they’re hunted for delicacies like shark-fin soup.

Despite more than 321 million cubic miles of “shark-infested” ocean around us, there were just 84 unprovoked shark attacks last year worldwide, and only four were fatal. Thanks to pop culture portrayals of sharks as serial killers, it’s easy for us to ignore the fact that a shark is far more likely to die by our hands than vice versa.

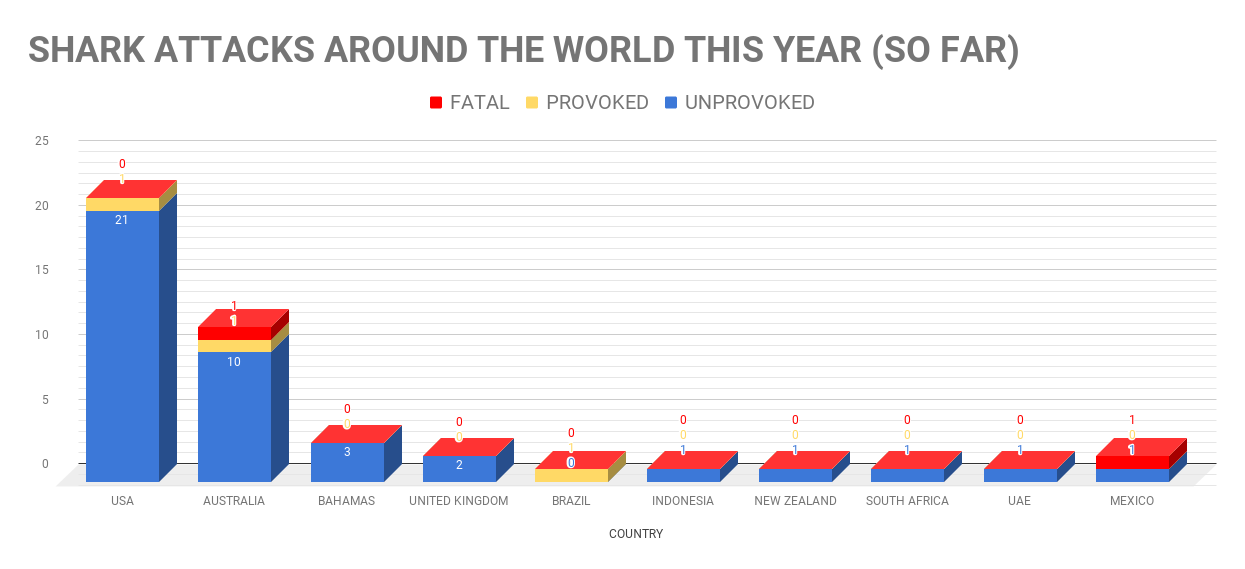

Just look at the 2017 data from the Global Shark Attack File:

Data from Global Shark Attack File. (Ritu Prasad/MEDILL)

Two fatalities and 44 attacks have been reported this year across the globe. It’s worth noting that one of the attacks was the result of a man trying to lasso a shark; another because a tourist wanted a selfie with one—you only live once, after all.

Read on for 8 facts about sharks that have (almost) nothing to do with how much you think they want to eat you.

A caribbean reef shark, Carcharhinus perezi, cruises through waters in the Bahamas. (Photo courtesy Stephen Kajiura)

1. Your dog probably wants to eat you more than a shark does

Fatal dog bites occur 33 times more frequently than fatal shark bites, according to statistics compiled by the Florida Museum of Natural History.

“We’re not part of their diet,” says Stephen Kajiura, marine biology professor at Florida Atlantic University, adding that if sharks wanted to snack on humans, many more of us would be dead by now. “They’re not out to get you, it’s often a case of you’re in the wrong place at the wrong time.”

A study in the 1980s took it further, finding that for every person bitten by a shark, 25 people in New York are bitten by other New Yorkers. Yikes.

2. 2017 is the year that sharks get FitBits too

One of Kajiura’s 2017 projects? Tagging your friendly neighborhood shark with, essentially, a personalized FitBit.

“[We’re] instrumenting the sharks with tags that will tell us how many tail-beats the shark makes, how fast it’s moving, [and if] it jumps and spins out of the water,” Kajiura says. We know where they’re going and how they’re coming back, Kajiura explained, but we now have the chance to get details on their day-to-day behaviors too.

3. Sharks need to move to breathe

As for getting those miles in, for sharks, it’s less an exercise activity than an exercise in staying alive.

Most sharks are mouth breathers. That is, they need to pass water over their gills in order to extract oxygen from the water. They do this by swimming jaws-open to push water across their blood vessels. Some lucky species like nurse, angel, and lemon sharks have strong enough neck muscles to circulate water even while the shark is resting, but for most sharks, to stop swimming is to stop breathing.

This is why nets are particularly dangerous to sharks: if they get trapped and can’t swim through, they will drown.

4. Too wild to stop: Great Whites can’t survive in captivity

Roaming the seas is such an intrinsic part of shark lifestyle that the longest time a Great White survived in captivity was just six months—and it died shortly after being released.

Great whites can grow to more than 15 feet in length, so it’s difficult to build a tank big enough for them. They’re also open water swimmers with a penchant for swimming long distances rather than circling in one place (scientists recently tracked a great white that swam from South Africa to Australia in 99 days).

When you cage a creature used to the freedom of the ocean, the sad but obvious thing happens: they run into the glass constantly, injuring themselves, stressing themselves, and eventually, the cage kills them.

After 17 years, this Lanternshark has been identified by researchers as a new species. (Photo courtesy Stephen Kajiura)

5. Not all sharks are supersized—the smallest is the size of your hand & it glows

The smalleye pygmy shark maxes out around 15 centimeters long. It’s also bioluminescent, with eyes (small, yes) that gleam, opalescent.

Around 10 percent of the shark species we know of are similarly bioluminescent, including a new species discovered by Kajiura and a team of scientists. The species is a new type of Lanternshark, a deep-ocean dweller that uses lighting techniques for both camouflage and coquetry.

“They often use this because they need some sort of visual cue to make sure they’re mating with the right species,” Kajiura says. “You can tell what species it is just based on the patterns on the side,” much like the way we distinguish butterflies based on coloration.

A blacktip shark, Carcharhinus limbatus, weaves through fish off the coast of Jupiter, FL.(Photo courtesy Stephen Kajiura)

6. Sharks can’t get cavities

Add it to the list of their enviable qualities. Shark teeth contain fluoride, which keeps them cavity-free. Given that sharks generally have about 50 teeth and some species have as many as 300, it’s clear why they evolved to not need much dental work.

7. Sharks basically have metal detectors for noses

Thanks to electric receptors on their snouts, sharks are able to detect electrical fields in the water. These receptors, called ampullae of Lorenzini (after the 17th century anatomist who discovered them), help sharks sense what’s out there in dark waters.

Kajiura’s favorite shark, the scalloped hammerhead, is particularly well suited for this task.

“It’s like a giant metal detector coil,” Kajiura says—and with a head double the size of other sharks, there’s a clear advantage for the hammerhead. “It sweeps a bigger swath of the sea floor with its electro receptors.”

Another side effect of this unique head?

“They are so cute!” Kajiura adds. “The little babies are all head- all head and a skinny little tail. They look like clumsy puppy dogs.”

Fun fact: shark babies are in fact called pups, so the analogy fits.

The hammerhead, with its famously shaped skull, is better than most sharks at detecting electric fields on the sea floor. (Photo courtesy Stephen Kajiura)

8. Some sharks keep their eyes toasty in cold waters with built-in heaters

Like most fish, sharks are cold-blooded, which means their blood temperature is the same as the water around them. So what’s a shark out in the cold to do?

Lamnid sharks, the family of white sharks that includes great whites, have a unique vessel structure called retia near their eyes that helps warm the blood sent to the eyes and brain. This way, the shark can maintain the resolution of vision it needs to detect moving prey. For sharks that take on deep dives and move through many temperatures in a short time span, retia also help keep the eyes and brain at a stable temperature. These sharks also have a special vein that moves warm blood from the muscles to their spinal cord, keeping their nervous system nice and toasty.