WASHINGTON – Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin has said he wants to work on housing finance reform – including the future of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac — in the second half of 2017, but the issue has stalled in Congress and is unlikely to get much attention this year, experts say.

Mnuchin told the House Financial Services Committee in July that a new system should increase private sector participation and protect taxpayers. He also said it’s too early to decide whether the two big government-sponsored enterprises – Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac – are needed in a reformed system, and if policymakers end up with a proposal includes some type of explicit guarantee, it would have to keep taxpayers off the hook.

Rep. Jeb Hensarling of Texas, chairman of the House Financial Service Committee, wants to remove government backing from the housing finance market.

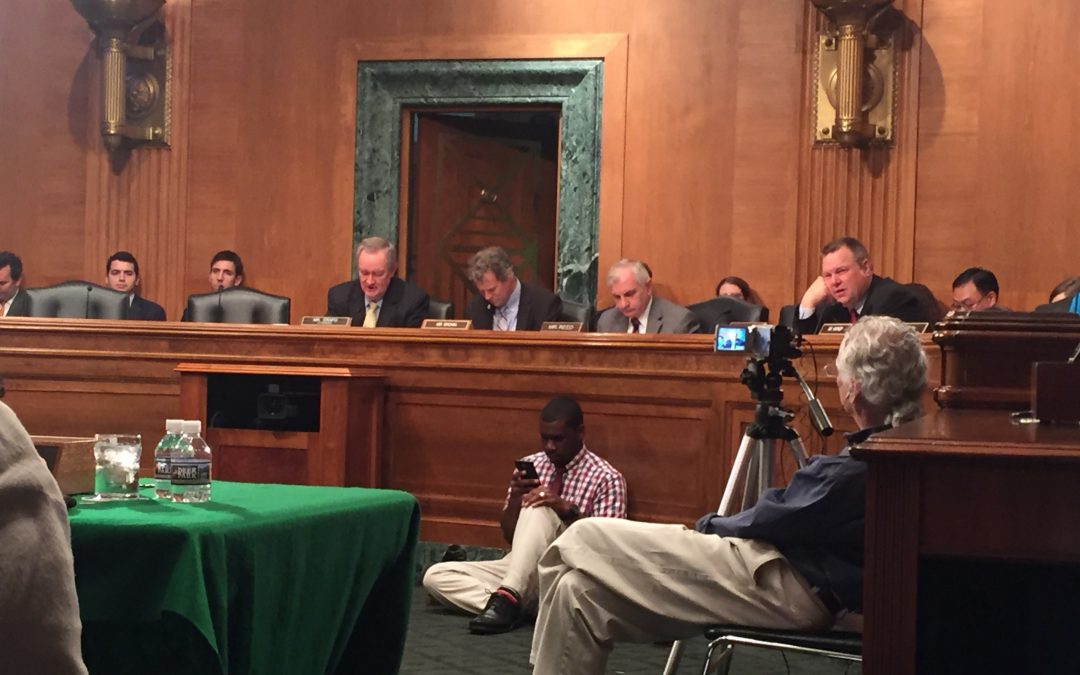

But Sen. Mike Crapo of Idaho, chairman of the Senate Banking Committee, wants to replace Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac with a new government agency that provides government guarantees to the market. But the last time the committee pushed that idea in 2014, the measure never gained full congressional approval and died.

Despite Mnuchin’s stated commitment to housing finance reform, chances of action on either idea this year aren’t much better than in 2014, financial experts say.

“I think the chances of anything actually happening this year is very low,” said Christopher Whalen, a financial analyst and chair of Whalen Global Advisors LLC.

Thomas Vartanian, a partner in the law firm of Dechert LLP and former general counsel of the agency that oversees Freddie Mac, had the same prediction: “We’ve got nine years of zero agreement on that issue. We’ve got a divided and very partisan Congress. I would say the chances for some congressional action quickly would not be very high.”.

The federal government seized the two giant mortgage-finance companies in 2008 and gave them $187.5 billion to avoid default. Under the current system, the federal government has backed approximately 70 percent of all U.S. mortgages.

Under a 2012 agreement, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac have to turn over their profits to the Department of Treasury, along with nearly 80 percent of their common stock. Their capital buffer is scheduled to be drawn down to zero at the end of 2017.

At that time, the companies would need more bailout money if they suffered an earnings loss. Which is the only reason housing finance reform would move to the congressional front-burner, the experts said.

“It is the only thing in the horizon that will be sure to happen and may press the Congress to do something,” Whalen said.

Any changes to government guarantees will impact popular mortgage products like the 30-year fixed rate mortgage and affect mortgage affordability.

“Many of our Republican colleagues support equal access to smaller lenders … but they turn around and oppose any form of government intervention to help lower-income or minority borrowers,” said Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., at a hearing in July. “We need thoughtful government intervention to make sure that the mortgage market works for both small lenders and for credit worthy low-income borrowers.”

Supporters of government guarantees through government-sponsored enterprises say they are key to preserving the ability of lower-income Americans to participate in the housing market.

“What government has done is turned all these mortgage securities into basically a commodity, and the only thing investors need to worry about is interest risk and market risk,” Whalen said. “For lower-income and middle-income borrowers, the probability of default is higher. They [investors] probably need some kind of government backstop.”

But Republicans in the House, including Hensarling, want to remove government guarantees to protect taxpayers from bailout risks.

Supporters of this plan say the government-sponsored enterprises increase housing prices by lowering underwriting standards and down payments and make houses less affordable for lower-income buyers.

“The Senate is doing the exactly the wrong thing. They are talking about another government program that will guarantee mortgage-backed securities. The purpose of it is to reduce the cost of mortgages, and the effect of doing that would be to drive up housing prices,” said Peter Wallison, senior fellow in Financial Policy Studies at the conservative American Enterprise Institute.

But both Senate and House banking committees say they are not giving up on their housing finance reform proposals, even though Congress has yet to take up other top Trump administration priorities like tax reform, funding for a wall on the U.S.-Mexican border and infrastructure funding – and a possible attempt to revive health care repeal and reform.

“At this point, we are working with members of the committee to see where we can get bipartisan consensus for a housing finance reform bill,” Senate Banking Committee spokeswoman Amanda Critchfield said.

On the House side, committee spokeswoman Sarah Rozier said the committee doesn’t “have anything listed or released at this point. The chairman plans to focus on housing finance reform later in the year, when they return from Congress’ recess.”