WASHINGTON – In January, Bnyad Sharef and his family flew from Iraq to Egypt on their way to Nashville, Tennessee – their new home.

But when they landed in Cairo on Jan. 27, they learned that President Donald Trump had signed an executive order banning entry into the United States for citizens of six majority-Muslim countries, including Iraq.

“We were blocked in Cairo on our layover because we made the trip on the same day the first travel ban was issued,” remembered Sharef, a featured speaker at an anti-travel ban rally at Lafayette Square on Wednesday.

The #NoMuslimBanEver rally was held shortly after U.S. District Judge Derrick Watson blocked Trump’s third iteration order and a federal judge in Maryland followed suit.

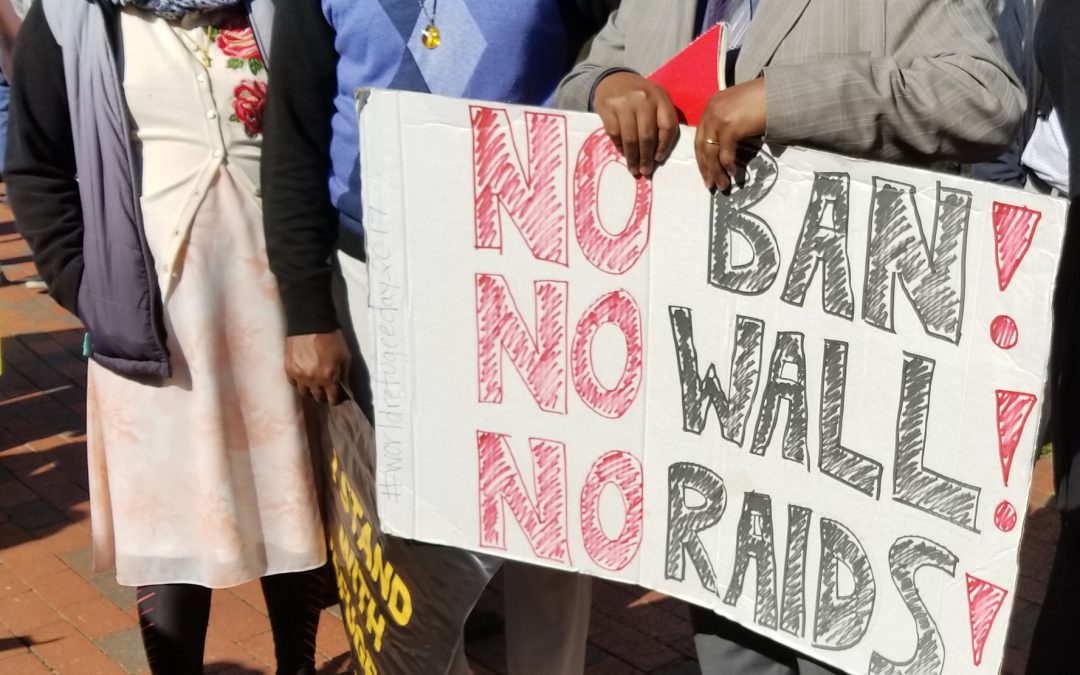

Nevertheless, hundreds gathered at the rally to oppose Trump’s orders, many displaying homemade signs and posters that declared their allegiances. Some of those posters included logos of organizations that supported the rally, like Oxfam, Amnesty International and others.

“I’m someone who has been through this and I want to tell the story of what it’s like to be affected by this ban and why we don’t want it,” Sharef said before addressing the crowd.

Ayelet Hines, a spokeswoman for T’ruah, the rabbinic human rights organization, stood on a park bench and held up a poster “My father was a Syrian refugee,” paraphrasing a Bible verse from Deuteronomy 26:5.

She explained that she feels connected to those who were hurt by the travel ban.

“My grandparents fled Hitler in 1936 and they were refugees who barely escaped with their lives,” Hines said, “If it weren’t for America’s open door and that core value, that core American value, that core Jewish value, I don’t know what would’ve happened to them.”

Rabbi Jack Moline, president of the Interfaith Alliance, echoed Hines’ sentiments.

“As a Jewish community we have enjoyed the blessings of America because we were welcomed, not always with open arms, but with open laws,” Moline said, “There are a lot of my brothers and sisters who need to be here, who need to be able to get in here, and who need to be with their families.”

When Sharef and his family were blocked from traveling to the United States, a two-year planning process in which they obtained valid visas, was reversed. His parents had already sold their home and their belongings and quit their jobs in Erbil, Iraq.

“We basically had no life left in Iraq,” he said. “When we were turned away, we were desperate. We didn’t know what was going to happen.”

Sharef also said that because of his father’s work as a subcontractor with the U.S. Agency for International Development, their lives were in danger, particularly from groups like the Islamic State.

“A lot of my dad’s colleagues were assassinated because of their work with the U.S. government,” he said.

After spending 10 anxious days in Cairo, he and his family received special exceptions to the ban, largely because of the danger they faced in Iraq, and made it to Nashville.