WASHINGTON— A 30-year-old recently married medical resident who is about to graduate as an orthodontist planned to move on to a career in private practice. Instead, she and her husband are moving in with her parents and she will work in a health care corporation.

The reason? Dr. Lauren Wiese graduates at the end of the month from the University of Maryland School of Dentistry in Baltimore with student loan debt totaling $411,714.

Even though Wiese attended college on a full-tuition scholarship and received a $120,000 interest free loan from her parents that covered her first two years of dental school, she had to take out interest-bearing loans for her final two years of dental school plus her three-year residency. She knows her situation could be much worse.

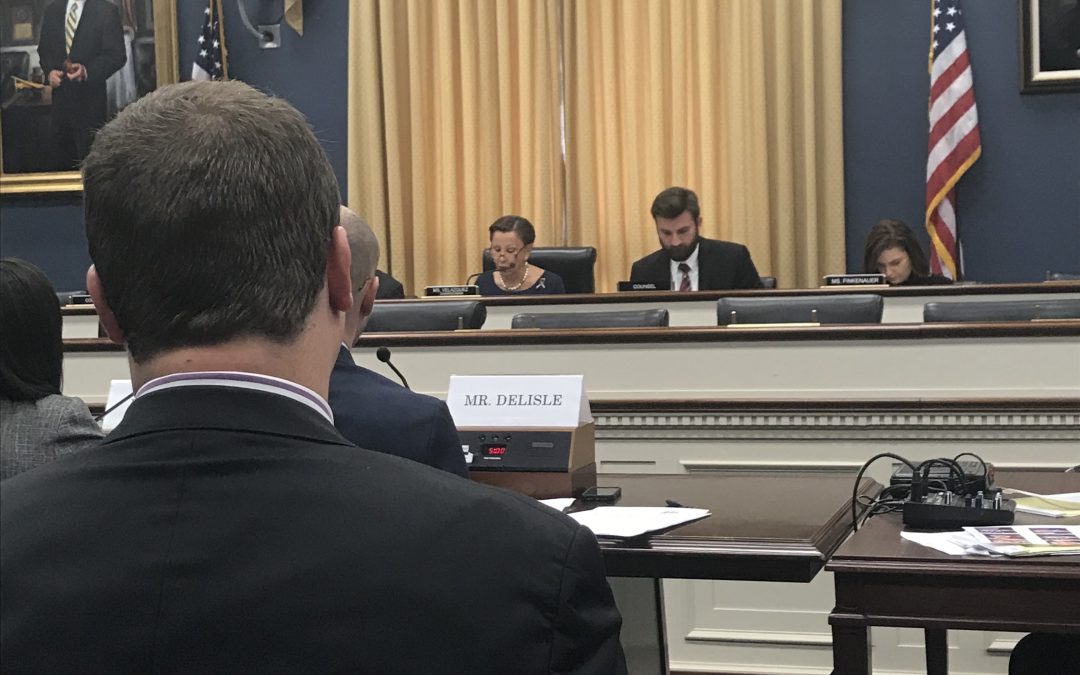

“Some of my classmates were not so lucky and have loans from college, private loans from post-baccalaureate programs, federal loans for a private dental school and federal loans for residency as well,” she told the House Committee on Small Business on Wednesday. The committee was investigating how student debt is preventing large swaths of doctors from pursuing private practice.

According to the credit reporting website Experian, overall student debt reached $1.4 trillion in the first quarter of this year. The Department of Education said a significant portion of that debt is for graduate and professional degrees.

The Association of American Medical Colleges predicts a physician shortage of up to 104,900 by 2030, with primary care – often private practice doctors — making up roughly half.

Rep. John Joyce, R-Pa., who is a dermatologist, told the committee that student debt is not the only barrier preventing doctors from pursuing private practice, but called for his colleagues to pass a bill that would allow dental and medical residency students to defer interest on student loan debt until after the completion of their programs.

Dr. Sandra Norby, founder of HomeTown Physical Therapy in Des Moines, Iowa, has found it difficult to hire for her private practice. She says her patient load is high, but she’s struggling to hire another physical therapist.

“As I have spoken to my fellow private practice owners from across the country, they too have spent many sleepless nights worrying about their practice and the patients they serve. How will they recruit and fill vacant positions?” Norby told the committee.

Norby blames the student debt crisis for doctors deciding not to pursue private practice. While her debt is paid, she is a co-signer for her three sons’ loans, which resulted in higher interest loans for her private practice. She acknowledges many doctors are unwilling to take on more debt to start a practice.

Wiese agreed, saying she is looking at the corporate dental path instead of entering private practice until she can pay down some of her debt.

But Jason Delisle, resident fellow at the conservative think tank American Enterprise Institute, said the federal government has income-based loan repayment programs that cap payment at 10 percent of discretionary income and public service loan forgiveness programs that should help doctors pursue their areas of interest.

The real reason doctors aren’t pursuing private practice is that tuitions are way too high compared with the earnings potential of graduates, he said.

“The price that universities are charging for many graduate and professional programs, including many in medical fields, are out of line with the income borrowers expect to earn. Borrowers need some protection from such overpriced credentials,” he said.

Wiese said paying off her loans will impact more than her professional future.

“My student debt is going to impact when my husband and I will plan to start a family. Few of the employment opportunities I have seen offer paid time off or maternity leave,” she said.