“The Oval” at Spelman College during student move-in day. (Kelly Rissman/Medill)

ATLANTA — While Aaron Greene was packing to head back to Clark Atlanta University for his junior year, he stumbled upon a college bill at his mother’s house in Stone Mountain, Georgia. The number was so large that he figured it had to be a phone number.

“I know my mother is not paying this much money for school,” he said. “We don’t have that.”

Though his mother, Di-Anne, already had $40,000 in student loans from her own graduate school education, she has taken out $42,000 in Parent PLUS Loans for Aaron — and she had kept him in the dark about the cost.

“I didn’t want to give him the pressure of starting out in college, worrying about grades as well as the finances,” she said. “But I probably should have [told him] so that he could get a better understanding of the sacrifice that’s been made.”

Parent borrowing is a sacrifice that many black parents make to pay for their children’s college education, and is especially prevalent among families whose children attend historically black colleges and universities. The federal government’s Parent PLUS program makes attending college a reality, closing the gap between the cost of college and what the student receives in grants and other loans.

While it may sound like a lifeline, the Parent PLUS Loan program can cause economic complications for families.

The loan program was introduced in the 1980s as a way for middle- and upper-income parents to help their children pay for college while keeping their assets liquid. It has since become more popular among lower-income parents. That’s possible because the program does not check the ability to repay, only considering the borrower’s credit history.

When parents borrow, the debt can weigh down families for generations. But the burden falls particularly hard on low-income, black families.

Few white families with low incomes take out the loan — just 10% of white Parent PLUS borrowers earn $30,000 or less. Comparatively, 40% of black Parent PLUS borrowers have incomes that low.

Atlanta colleges illustrate this dichotomy of borrowing.

Parents of students at three of the city’s historically black colleges — Clark Atlanta University, Morehouse College, and Spelman College — combined took out more than $102 million in Parent PLUS Loans in 2018. Meanwhile, parents of students at Emory University — which has nearly the same number of students as those three historically black colleges and universities together — borrowed only $7 million in Parent PLUS Loans that year.

Parents borrowing for their children’s education isn’t a new phenomenon, though. The program has existed long enough for families to see one of the consequences of taking out large loans: generations of overlapping debt.

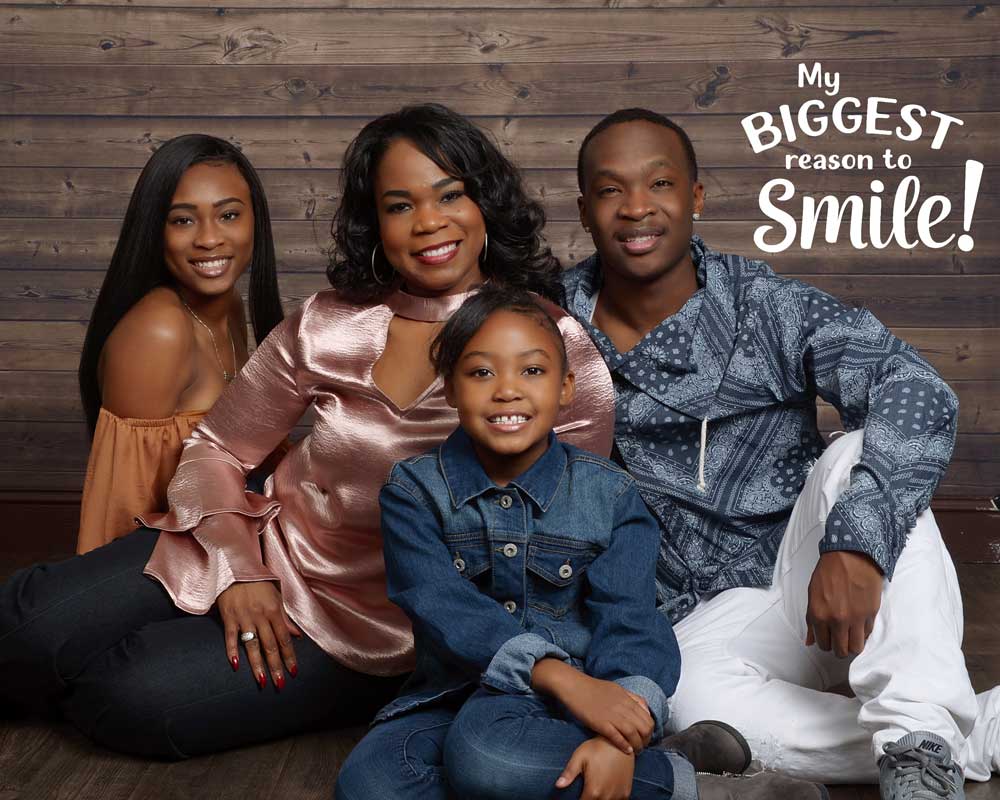

Prairie View A&M University graduate Tania White with her children Tianna, Taniyah Sumberlin and Gary, Jr. Her son, Gary, attended PVAMU for three years and serves in the U.S. Air Force. Tianna is currently a junior at PVAMU. (Photo courtesy of Tania White)

In Texas, Prairie View A&M University graduate Tania White needed her mother to take out Parent PLUS Loans for her undergraduate education 30 years ago. White’s mother borrowed a total of $12,000 for White’s three years of college. She is still paying it back. Since White’s graduation in 1992, her mother’s debt has accrued to over $100,000. White said the interest rate on Evans’ $100,000 debt is around 9%.

“You know how something is so outrageous where you have no expression or feeling behind it? That’s where we are with that,” White said, remarking that paying back student debt has become a routine for her family.

Despite seeing her mother’s debt accumulate, White resorted to Parent PLUS Loans to pay for her daughter’s study abroad trip. White now owes over $200,000 between her own and her children’s student debt.

This generational pattern of borrowing is not uncommon, since the Parent PLUS program casts debt across all generations — not just young people affected by federal student loans.

“We wanted to be the group that breaks generational poverty,” said Joy Evans, mother of a Paul Quinn College graduate, referring to her family’s three generations of college loan borrowing.

Intergenerational student debt may be a product of the length of time it takes families to repay the hefty loans. Parent PLUS Loans often take five to 20 years to repay because many of the borrowers are approaching retirement age, leaving less opportunity for promotions or time for them to accumulate enough funds.

As a result, some parents said they hope their children will help pay off the PLUS Loans after they graduate. For instance, one father took out Parent PLUS Loans for his youngest daughter to attend Coppin State University in Baltimore, Maryland.

“I’m concerned and a little worried about the debt,” said Perry Collins. But “it is our hope that [our children] will get to the point where they can provide for themselves.”

Collins said his debt is accumulating quickly — between a mortgage and his children’s student loans. He hopes his children will assist him in the repayment process.

Families that attend HBCUs are a prime example of the program’s consequences, Collins said, “because it’s the less privileged and less wealthy that are sending their children out to these things and that’s their only means in most cases,” Collins said.

Parent PLUS Loans may add another struggle: instant repayment. Unlike federal student loans, parent borrowers are expected to immediately begin repaying the loan. Depending on how much they owe, the amount could take decades to pay back, furthering the chance of debt overlapping across generations.

Morehouse mother Vanessa Manley predicted it will take her and her husband 15 to 20 years to pay back their $30,000 in Parent PLUS Loans, but the loans were worth the investment.

“Some parents invest in material things. I invest in my child,” Manley said. Her son started at Morehouse in fall of 2019.

For many parents, the value of sending their child to an HBCU is worth any cost. They see these institutions as pathways to success.

Roderick Hester discusses repaying $200,000 in Parent PLUS Loans that he took out for his three daughters, all of whom attended Spelman College. (Ebony JJ Curry/Medill)

Roderick Hester just dropped off his third daughter at Spelman College. He took out Parent PLUS Loans for each of them. “If this will give my child the best opportunity to be successful in life,” he said, “This was the avenue I had to pursue. There wasn’t a lot of options.”

Hester owes over $200,000 in Parent PLUS Loans.

“I don’t really know how I’m going to pay it back, but I’m planning on it,” Hester said. “Whatever I need to do is what I have to do.”

Some parents consider HBCUs a unique opportunity for their children to experience a predominantly black environment.

In order to pay for her son’s first two years at Morehouse, Carmelita Farrah borrowed $70,000 in Parent PLUS Loans. The idea that he would “experience his heritage” at Morehouse trumped her financial strain.

“The obstacles are stacked against him as a black man, so what will set them apart?” she said. “Hopefully an education. After that, a career. Because it’s a struggle. It really is.”

Just last spring, a billionaire Morehouse alumnus brought national attention to the student loan issue at HBCUs when he made a surprise announcement at graduation: he said he would pay off every 2019 graduate’s student loans. He challenged other alums to do the same for future classes.

At Morehouse’s graduation ceremony last May, billionaire Morehouse alum Robert Smith announced that he would pay off every 2019 graduate’s student loans. He challenged other alums to do the same for future classes.

Frank Lawrence Jr., a Morehouse Alumni Association member and 2019 graduate whose debts were cleared by Smith’s gift, said the Alumni Association is “trying to encourage more alumni to give back.”

Other HBCUs have employed their own strategies to reduce student debt. In 2015, Paul Quinn College implemented a work-study model. The number of parents borrowing PLUS Loans has decreased over the four years since the program’s launch, according to President Michael Sorrell.

In addition to institutions attempting to lower college debt, the nonprofit United Negro College Fund reported that this year alone, it is providing nearly $100 million in scholarships to over 7,200 students of color. Not every student wins a scholarship, though.

“Loans are almost necessary without any scholarships, but students and their families have to shop around to find the best loans for them,” said Brian Bridges, UNCF’s vice president of research and member engagement.

“Parent PLUS Loans are an essential college financing option for some students and parents that can be improved; however, the program must be repaired, not repealed,” Bridges added.

Other experts agree that the Parent PLUS program should be improved.

The program is “doing a huge disservice to students of color and families of color when we’re saying that they can borrow however much they want,” said Colleen Campbell, director for postsecondary education at the liberal think tank American Progress.

Campbell added that families should not be allowed to spend more than they can contribute.

“If a family can only contribute $5,000 to their student’s education in a year,” Campbell said, “that’s probably the amount you should allow them to borrow.”

(This story was reported by Holly Barker, Josephine Chu, Ebony Curry, Andre Earls, Apoorva Mittal, Lu Zhao and Priscilla Zhu. It was written by Ariana Puzzo and Kelly Rissman.)