As Census Day draws nearer, on-the-ground partners with a trusted voice in the community will be vital to ensure an accurate count, especially among populations who traditionally get undercounted, experts on the decennial count say.

For the first time, the Census Bureau asking a majority of Americans to complete the census online in 2020, saying that this technological facelift is easier, greener and more cost-effective.

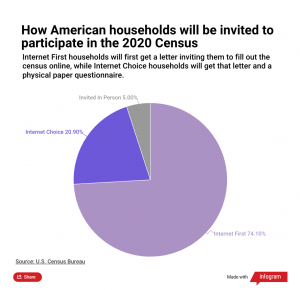

Ninety-five percent of households will receive a census invitation in the mail by March. About 78% of these households will be asked to immediately respond online or by phone, deeming them as “internet first.” The remaining households, or “internet choice” households, will receive a paper questionnaire as well as an invitation to respond online. The 5% of households that do not get an invitation in their mailbox at all will receive it when a census worker physically drops it off.

These internet choice households were chosen because they have a low response rate to the Census Bureau’s yearly American Community Survey, as well as low internet rates, a high elderly population, or low internet subscription rates. The bureau randomly selects 3.5 million addresses each year to respond to the survey.

Because of this new strategy, the bureau is devoting fewer resources to in-person enumeration based on the assumption that most people will fill out their form online and to save money. The bureau is hiring 500,000 temporary workers for 2020, compared to 635,000 in 2010.

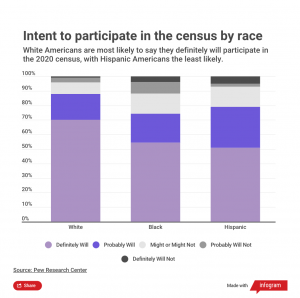

One in ten Americans do not use the internet at all, according to the Pew Research Center, and the share is higher among rural and minority residents. The often-critical person-to-person contact that is only achievable through human enumerators is critical among many hard-to-count populations; in a 2018 census test in Rhode Island, only 39% of African Americans self-responded online. In that test, 52.3% of participants self-responded: 61.2% of them online, 7.5% by phone, and 31.3% with the paper questionnaire.

Dr. Ron Jarmin, the deputy director of the Census Bureau, wrote that he was “encouraged” by the Rhode Island results and by the “systems and technology [they’ve] put in place for the public to safely and securely respond to the 2020 Census” in a 2018 blog post. Enumerators used iPhones to receive assignments and transmit data, which allowed them to complete 1.56 houses per hour compared to 1.05 houses per hour in 2010, according to Jarmin.

Although census officials cite savings as one reason for going online, the slimmer budget of conducting the 10-question census online has yet to be proven: While the 2010 census ended up costing $13 billion, the Government Accountability Office estimated this go-around to cost at least upwards of $15.6 billion. Part of that cost, the office said, has to do with implementing various IT systems for the online count.

The goal of these logistical acrobatics is, of course, to get an accurate count of every person living in the country, as mandated by the Constitution. The census determines how federal funding is parceled out and the number of representatives each state gets in Congress. By the bureau’s estimate, the 2020 census will determine the distribution of over $675 billion in federal money for health care, education, social services, infrastructure and many other programs.

Populations such as children, people of color and immigrants, however, tend to be undercounted in the census. The Census Bureau undercounted almost one million children in 2010, many of them black or Hispanic, according to an analysis from the bureau. They undercounted 2.1% of the overall black population, 1.5% of the overall Hispanic population, and 4.9% of American Indians and Alaska Natives living on a reservation.

Undercounting Latinos “would severely diminish the accuracy and value” of any data used to allocate federal spending and policy, said Arturo Vargas, CEO of the NALEO Education Fund, during a House Oversight Committee hearing on Jan. 9. Latinos are the nation’s largest minority group making up 18.1% of the population, Census data show.

“Our communities need resources, and the only way we can get those resources is to be counted,” said Marla Bilonick, the executive director of the Latino Economic Development Center, a non-profit that serves the Washington, D.C.-area Hispanic population.

Many communities have formalized Complete Count Committees to educate and motivate residents, especially hard-to-count populations, to participate in the census. Member organizations of complete count committees already have the “knowledge, influence, and resources to educate the public and promote the census,” according to the bureau.

“It’s impactful to have a local committee that is extremely diverse that can speak to different segments of the population to explain to them what the census is, what is is not, and how it’s important for them and their family,” said Darrell Moore, the executive director at the Center for South Georgia Regional Impact at Valdosta State University. The center studies 41 rural counties in Georgia and partners with community leaders to encourage economic growth.

The LEDC is part of Washington D.C.’s Complete Count Committee and received funding from the city to spread awareness of the census. The organization plans to integrate census education into current programming, which relies heavily on door knocking and person-to-person contact.

“Our organization has a credibility in the community,” Bilonick said. “That goes very far in terms of having power to encourage someone.”

Physical interaction is essential, even if it’s more labor intensive, Bilonick said. “It’s about integrating that messaging into everything we do that touches human beings.”

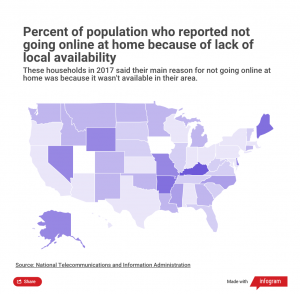

The hard-to-count population overlaps partially with populations least likely to have internet access. The 2015 American Community Survey found that 36.4% of black households and 30.3% of Hispanic households do not have a broadband internet subscription or a computer of any type. By comparison, 21.2% of white households do not have broadband or a computer.

Moore said that broadband access in rural America may impact census participation, but a lot of his work is dedicated to educating community members about the resources available. Twelve percent of Lowndes County, where Valdosta State University is, does not have adequate broadband internet services, according to the Georgia Department of Community Affairs. Moore said that a key strategy in Georgia is making sure people knows about all three options for census participation: online, over the phone, and in person.

“I just know our community and others that we’re working with have a really good plan to try and reach everybody in the county,” he said. “I’m hopeful that everyone is doing that.”

Public libraries may offer a solution for households without internet access, as many libraries across the country are already reliable alternatives for households without computers; minorities and adults with low-incomes are most likely to use computers at a library, according to a 2015 Pew Research Center report. Almost 100% of Americans and almost 99% of hard-to-count populations live within 5 miles of a public library, according to the Center for Urban Research.

Libraries have “long played a role” in the census, according to Public Library Association Deputy Director Larra Clark. Not only did libraries support the 2010 Census by hosting workers and acting as outreach sites, but they also used the collected data afterwards to better serve their cities.

“In 2020, this coordinating role that libraries have played is even more important with the online response option,” Clark said. “Every time there is a government service that moves online either partially or completely, libraries tend to see an impact from that. We know that millions of Americans do not have high-speed internet at home and we also know that libraries are the leading source of no-fee access to the internet.”

In December, the American Library Association awarded 59 “mini-grants” of $2,000 so libraries could better serve hard-to-count populations. The money will be used to purchase additional computers and mobile hotspots, educate families about undercounts, and equip mobile libraries to offer the online response option in geographically isolated communities.

“The efforts of these 59 libraries will shine a light on all the library workers across the country who are shouldering efforts to reach and inform their communities—especially vulnerable and hard-to-count populations—about the importance of a full and inclusive count,” ALA President Wanda Brown said in a press release.

Clark said that 90% of the 500 library applicants for the grant reported not receiving any funding whatsoever for census support. She stressed the importance for those libraries to seek funding opportunities through city governments, non-profits, and local businesses so that they can be at a maximum supportive capacity.

“A complete count is really about equity and it’s about accuracy,” she said. “Librarians believe that everyone counts, so that means everyone should be counted.”

Partnerships at the national, regional and local level share the common goal of making sure every resident gets counted this census.

“It’s not political. It’s not anything else,” Moore said. “You’ve got to have someone that person can trust to compel them to participate in the census. You can have all these plans, but if you don’t have an active local group that has local stakeholders that those people respond to and they trust, you’re not going to be as effective as what we’d like to be.”