WASHINGTON — Despite being essential workers, domestic workers – especially those whose primary language is Spanish – are excluded from much-needed coronavirus relief, according to a National Domestic Workers Alliance report released Tuesday.

“This pandemic has been devastating for our workforce, creating dramatic losses in jobs and income, with limited access to forms of relief,” said NDWA Executive Director Ai-jen Poo. “Our economy is simply not working for domestic workers.”

Coronavirus relief should ensure domestic workers are paid higher wages, have access to benefits like paid sick days, paid family and medical leave, health insurance and are offered a path to citizenship, the report said. The 2.5 million domestic workers include nannies, home care workers and most commonly house cleaners.

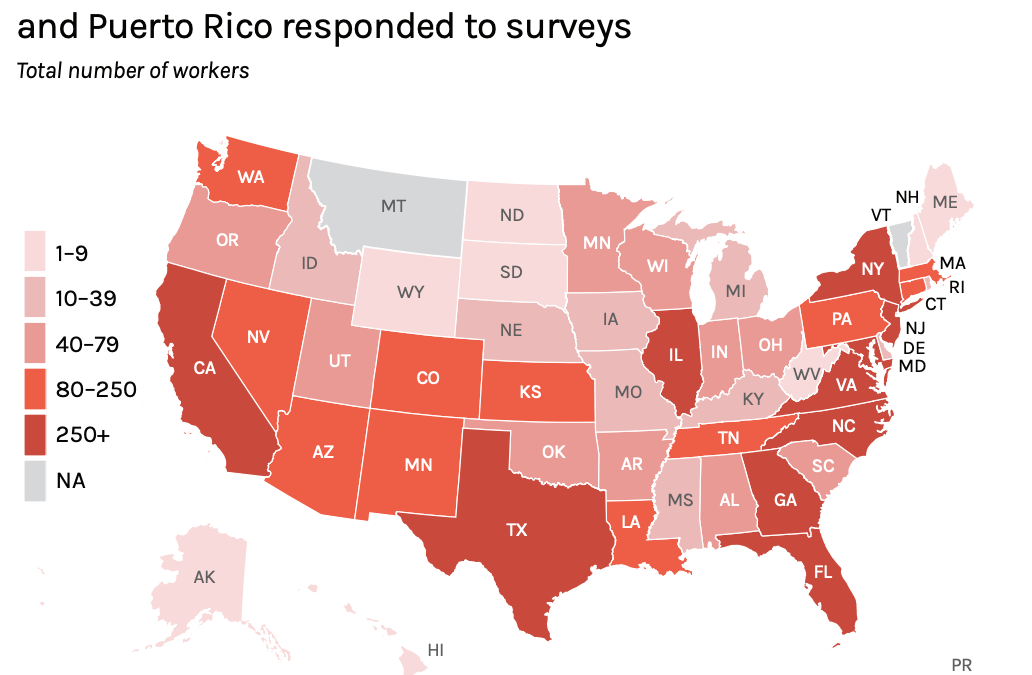

In a survey of 20,000 Spanish-speaking domestic workers, more than half were unable to pay their rent or mortgage. Many were unsure about their ability to afford food in the next two weeks, the study said.

More than 90% of Spanish-speaking domestic workers surveyed lost their jobs in March. By September, 36% were still unemployed, four times their unemployment rate before COVID-19. Three-quarters didn’t receive compensation when they lost their jobs, the survey found, and the majority did not apply for unemployment insurance, believing they didn’t qualify.

Poo said less than a third of Spanish-speaking domestic workers received a $1,200 stimulus check under the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act.

Those who are still employed are working fewer hours, with a majority working less than 31 hours a week, the survey found. They’re also earning lower hourly wages, with most earning less than $300 a week.

Rosina Rodriguez, a Philadelphia house cleaner, said she used to clean about 13 houses before the pandemic. But starting in March, she had no work. Her husband, a restaurant worker, was also let go. Though she was able to work again in June, it was only at about three houses.

Her family didn’t qualify for the government stimulus check because they are a mixed immigration status family.

“As domestic workers, we deserve to be cared for by this country because we take care of your children, your elderly and your homes,” Rodriguez said.

Amalia Hernandez, head of a caregiver group in New Mexico, said she used to manage 20 workers and now only manages four. Her husband has only been able to work for a week or two per month.

“We need the government to represent us and provide the protection we need to continue working safely in the pandemic and beyond the crisis we are facing,” she said.

Half of Spanish-speaking domestic workers surveyed said they don’t have access to medical care, and more than half do not know if they have a food bank nearby. Though the majority of domestic workers are mothers of school-age children, more than a quarter lack a device for their children’s remote learning.

“For domestic workers who have continued to work through the pandemic as essential workers, it has meant a series of impossible choices for how to continue to work on taking care of your own children and families and staying safe while minimizing risk of exposure to the virus,” Poo said.